Jonathan Ochshorn

A version of this essay appears in Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Architecture, Fitzroy Dearborn (Taylor and Francis) Publishers

Text © 2003 Taylor and Francis Publishers. Posted on this web site only by permission of publisher. All rights reserved. Republishing this material, whether in print or on another web site, in whole or in part, is not permitted without advance permission of the publisher. Copyright status of images is unknown. Blue skies have been added by the author.

part 1 |

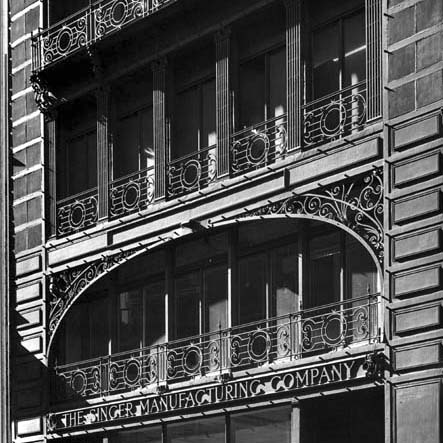

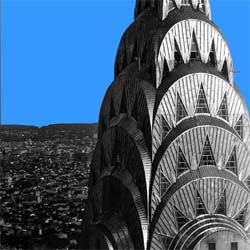

The office building. Chicago pioneered the steel-framed office building in the late 19th century, but it was in New York City that the true skyscraper was born. The 30-story Park Row Building of 1898 was soon surpassed in height by a series of early 20th-century stone-clad, steel-framed towers, braced internally with diagonal truss-work or made rigid with riveted steel portal frames. The most influential of these buildings was the Woolworth Tower (1913). Designed by Cass Gilbert, it was the tallest building in the world at the time, having overtaken the 50-story Metropolitan Life Insurance Building (1909) designed by Nicholas Le Brun and Sons, which had just surpassed the 47-story Singer Building (1907) designed by Ernest Flagg. At the beginning of the Great Depression, two steel-framed structures in New York City took skyscraper design to new heights, both literally and metaphorically: the Chrysler Building (1929) by William Van Allen and the Empire State Building (1931) by Shreve, Lamb and Harmon. The Chrysler Building is notable in this context for its crown of stainless steel cladding, one of the first extensive building applications for the newly-invented steel alloy.

Gilbert: Woolworth Building

Shreve, Lamb & Harmon: Empire State Building

LeBrun: Metropolitan Life Insurance

Flagg: Singer Building

Van Allen: Chrysler Building

Mies van der Rohe: Seagrams Building

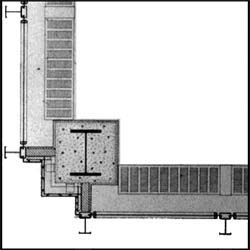

Seagrams Building: Plan Detail

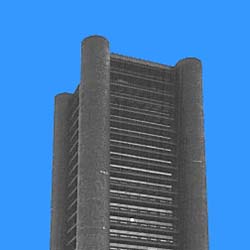

Roche & Dinkeloo: Knights of Columbus Building

SOM: U.S. Steel Building

Critics have argued about the architectural significance of these New York skyscrapers, and whether their exuberant facades of stone and brick—reminiscent in many cases of medieval towers and renaissance campanile—adequately express the nature of modern steel construction. While their impact as cultural icons is unquestioned, in general it is the earlier 19th-century Chicago buildings of Sullivan, Root, Burnham, and Jenney that are cited as exemplars of steel-framed building and precursors of modern design. After World War II, architects generally eliminated cornices and other traditional decorative elements derived from historic architectural styles in favor of the unornamented, rectilinear geometry associated with 20th-century modernism. Even so, the expression of steel framing remained problematic. For example, in Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson's Seagrams Building (1958) in New York City, the actual steel structure is first encased in concrete fireproofing and then hidden behind a metal and glass curtain wall. Even with bronze I-beams applied on the facade to stiffen the vertical mullions, expression of the actual steel framework is, at best, indirect.

A more direct expression of steel structure is achieved by exposing the characteristic flanged shapes of actual painted or corrosion-resistant steel beams and columns; or by celebrating the geometry of structural forms characteristic of steel—usually trussed or rigid frameworks evocative of steel industrial or civil engineering works. In the first case, Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo's use of exposed and unpainted corrosion-resistant steel girders for the Knights of Columbus Headquarters (1969) in New Haven, Connecticut and Skidmore, Owings and Merrill's use of partially-exposed painted steel girders (the flanges being covered for fire protection) in the U.S. Steel Building (1972) in New York City may serve as examples.

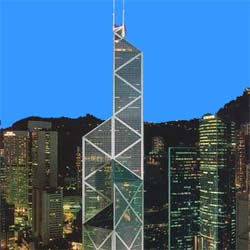

In the second case, the geometric form of truss or frame (rather than the shape of the individual elements) evokes steel structure. Three buildings by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill illustrate this approach. The Inland Steel Building (1957) in Chicago expresses its welded steel framework by locating the vertical elements of the framework outside the glass plane of the curtain wall; the Alcoa Building (1964) in San Francisco positions its triangulated steel bracing structure eighteen inches in front of its glass curtain wall; and the Hancock Building (1970) in Chicago sets its steel trusswork into the plane of the facade. Two buildings in Hong Kong provide additional examples based on the same principle. The Bank of China (1990) by I.M. Pei selectively expresses the complex triangular geometry of its steel frame, suppressing the articulation of horizontal truss elements and thereby changing the apparent pattern of the framework on the facades from a series of Xs — which would have negative cultural connotations — to a series of diamonds. Norman Foster's Hongkong and Shanghai Bank (1986) employs a more explicitly machine-derived aesthetic, using tension elements to literally hang sections of the building—eight floors at a time—from steel trusses which in turn are cantilevered from mammoth steel columns. In these examples the actual articulated steel structure is clad in sheet metal or, in the case of Pei's triangulated framework, stone veneer. Steel "exoskeletons" may also be unclad, as at the Foundation Cartier (1994) in Paris by Jean Nouvel, where abstract planar surfaces of parallel curtain wall screens are contrasted with exposed angular steel frames designed to provide structural stability.

SOM: Inland Steel Building

SOM: Alcoa Building

SOM: Hancock Building

Pei: Bank of China

Foster: Hongkong and Shanghai Bank

Nouvel: Foundation Cartier

part 1 |

Posted on web June 11, 2002; last updated Jan. 22, 2008 [minor re-formatting]