Jonathan Ochshorn

A version of this essay appears in Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Architecture, Fitzroy Dearborn (Taylor and Francis) Publishers

Text © 2003 Taylor and Francis Publishers. Posted on this web site only by permission of publisher. All rights reserved. Republishing this material, whether in print or on another web site, in whole or in part, is not permitted without advance permission of the publisher. Copyright status of images is unknown. Blue skies have been added by the author.

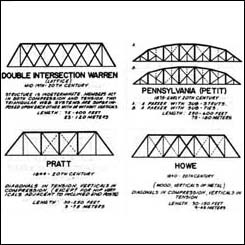

Trusses are triangulated frameworks used as spanning or bracing elements in buildings, bridges, transmission towers, and other structures. What distinguishes the truss from other structural forms is precisely its triangulation, from which two benefits accrue: first, the triangular geometry is inherently stable; second, all internal stresses — at least in "ideal" trusses whose bars are pinned together at the vertices of each triangular panel and whose loads are applied only at these pinned joints — are axial, i.e., limited to pure tension and pure compression.

Classical Truss Forms

Palladio's Trusses

Aside from its web of triangular panels, the truss has no intrinsic formal identity. Put another way, it is the specific pattern of internal diagonal, vertical, or horizontal bars (patterns that in many cases bear the names of their nineteenth-century inventors: Pratt, Howe, Town, Warren, etc.) that makes the structure a truss, not its overall shape. One may design an arch as a truss, a beam or column as a truss, or any number of tower forms — essentially beams cantilevered from the ground plane — as trusses. Advantages of truss construction include the following: 1) large trusses can be assembled from small members pinned together, facilitating production, transportation, and erection; 2) because all internal stresses are axial, with no bending stresses present, the truss is an extremely efficient structural form; 3) because trusses are typically assembled from individual elements bolted, welded, or nailed together, it is relatively easy to customize the overall shape of the truss in relation to external loads and spans; and to adjust the cross-sectional area of each member in relation to anticipated internal stresses.

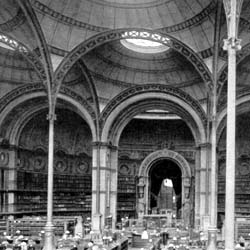

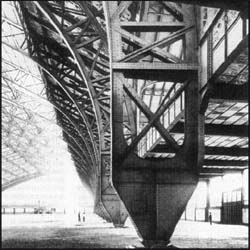

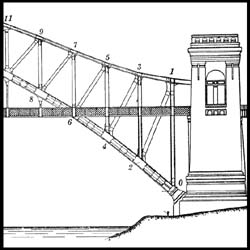

Trusses have been used for many centuries; Andrea Palladio illustrates truss bridges in his Four Books of Architecture as early as 1570. However, it is in the nineteenth century that industrial expansion—in particular the need for long-span exhibition and market halls, railroad terminals, and bridges—together with the development of engineering theory and improvements in the production of cast and wrought iron, and later steel, provide the motive and means for most of the advances in truss design that are exploited within early twentieth-century architecture. For example, the influence of nineteenth-century iron trusswork in Henri Labrouste's Biblioteque Nationale Reading Room in Paris (1875) can be seen in the vaulted ceiling above the Main Concourse in McKim, Mead and White's Pennsylvania Station in New York City (1910); while the tradition of long-span three-hinged arched trusses, epitomized in such nineteenth-century masterpieces as Contamin and Dutert's Galerie des Machines in Paris (1889), continues in twentieth-century structures like Peter Behrens's AEG Turbine Factory in Berlin (1909) and Tony Garnier's Municipal Slaughterhouse in Lyons, France (1913).

Labrouste: Biblioteque Nationale

McKim, Mead & White: Pennsylvania Station

Dutert: Galerie des Machines

Behrens: AEG Turbine Factory

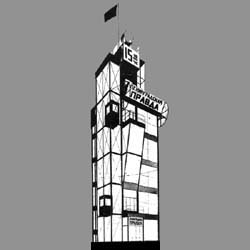

Vesnin: Pravda Building

Brinkman et al.: Van Nelle Factory

Lindenthal: Hell's Gate Bridge

A. Kahn: Glenn Martin Aircraft Plant

That being said, trusses are seldom found as expressive elements within the canon of mainstream early twentieth-century Modernism. Like Gothic buttresses, trusses are directly constrained by the geometrical logic of their structural form and, unlike prismatically pure columns and slabs, or expressively cast concrete elements, cannot easily be subsumed within Modernism's abstract, formal systems. It is only with Russian Constructivist and derivative projects from the 1920s and 1930s that trusses are first exploited as expressive elements within an explicitly Modernist context. Prominent examples include Alexander and Victor Vesnin's Pravda Building project in Moscow (1923) in which trusses are used as wind-bracing elements within a composition that includes bold text, angled planes, and glazed elevator towers; and Brinkman and Van der Vlugt's Van Nelle Factory in Rotterdam (1930) featuring dynamic horizontal and sloping trussed connecting bridges.

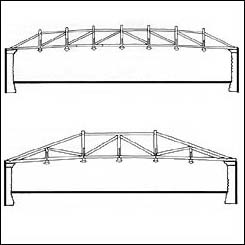

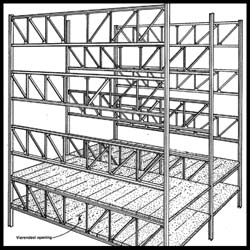

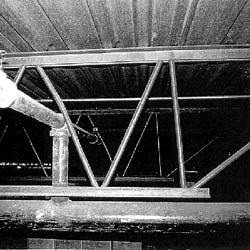

Early twentieth-century trusses are also important as infrastructure (bridges); and as industrial (long-span factory roofs), vernacular (ordinary wooden gable roofs) or pragmatic (hidden bracing or support) building elements. Gustav Lindenthal's arched Hell's Gate Bridge in New York City (1916) and Albert Kahn's Glenn Martin Aircraft Plant in Middle River, Maryland (1937) both utilize steel trusses that were the longest spans of their type when constructed. Steel trusswork is commonly employed — and hidden — within the central service "cores" of twentieth-century commercial buildings to provide bracing against horizontal wind and earthquake forces. Steel trusses are used to transfer loads over large spans — allowing hotel rooms to be placed on top of lower-floor ballrooms, or office buildings over railroad tracks — without themselves being expressed as part of the architectural form. William LeMessurier's development in the 1960s of a "staggered truss" system is another example of an entirely pragmatic invention utilizing trusses to minimize floor-to-floor dimensions in multi-story steel-framed housing or hotel blocks. Pre-engineered, factory-produced triangular wooden trusses made from common lumber connected with toothed metal plates are widely used in twentieth-century wood-framed residential roof construction. Open web steel joists, essentially off-the-shelf trusses first manufactured in the early 1920s, routinely achieve spans of up to 144 feet (44 m) by the end of the century and are ubiquitous in 1-story commercial and industrial buildings. Even precast concrete trusses, consisting of thin prismatic bars of reinforced concrete joined by steel gusset plates, are proposed for ordinary roof spans in England during World War II, as an expedient response to the short supply of steel.

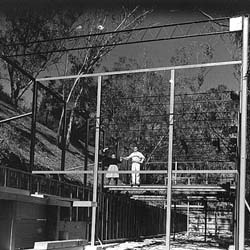

Where trusses are used deliberately as expressive elements within later twentieth-century architecture, it is most often by appropriating and reinterpreting the industrial, off-the-shelf, or pragmatic applications described above. Thus, ordinary steel open-web joists are used in California by architect Raphael Soriano as early as 1938, by Ray and Charles Eames in the influential house they built for themselves in Pacific Palisades, California (1949), and in various industrialized building system designs such as Ezra Ehrenkrantz's School Construction Systems Development, or "SCSD" (1961). Alvar Aalto's fan-shaped bolted timber trusses supporting the double-skin roof of the Säynätsalo town hall council chamber in Finland (1952) recall, in their detailing, vernacular heavy-timber roof trusses of nineteenth-century mill buildings. Mies van der Rohe's project for a Chicago Convention Hall (1953) visually integrates the diagonal members of its horizontal trusswork within the orthogonal pattern of its exterior curtain wall. Vertical wind-bracing trusses, typically hidden within the framework of tall buildings, are given similar architectural expression on the exterior of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill's Hancock Building in Chicago (1970).

LeMessurier: Staggered Truss

Wood Truss System

Open Web Steel Joist System

Eames: House Under Construction

Aalto: Säynätsalo Town Hall

SOM: Hancock Building

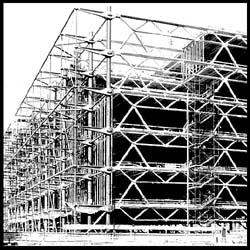

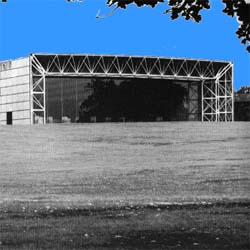

Trusses are commonly featured in so-called "high tech" architecture of the late twentieth century. Buildings within this genre reprise to some extent the Constructivists' interest in industrial production, but differ from Constructivist projects in at least two respects: high tech buildings tend to be less influenced by abstract compositional formulas; and often evidence a more theoretically grounded appreciation of structural systems as potential sources of architectural expression. In Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers's Pompidou Center in Paris (1977), virtually the entire architectural concept relies on exposed trusswork. Long-span interior floor trusses define column-free exhibition zones, and exterior wind-bracing trusses create the gridded diagonal pattern of the facades. Long-span roof trusses are used as dramatic and expressive elements in innumerable high tech buildings; examples include Norman Foster's Sainsbury Visual Arts Center near Norwich, England (1978), Michael Hopkins's Research Laboratories for Schlumberger in Cambridge, England (1984), and Nicholas Grimshaw's Waterloo International Rail Terminal (1994) in London, to name but a few.

Piano & Rogers: Pompidou Center

Foster: Sainsbury Visual Arts Center

Hopkins: Research Laboratories

Grimshaw: Waterloo Terminal

Further reading:

Most work published specifically on trusses focuses on their development before the twentieth century. For example, Yeomans (1992) traces the use and history of trusses, primarily in England, only into the nineteenth century. Ambrose (1994) includes a useful short history of trusses within a technical engineering reference. Condit (1961) contains a great deal of information on the refinement of trusses within early twentieth-century American bridges, skyscrapers, and industrial buildings. Wilkinson (1996) and Davies (1988) provide numerous images and examples of trusswork, especially within the late twentieth-century "high tech" genre.

Ambrose, James, Design of Building Trusses, New York: Wiley, 1994

Condit, Carl W., American Building Art: The Twentieth Century, New York: Oxford University Press, 1961

Davies, Colin, High Tech Architecture, New York: Rizzoli, 1998

Wilkinson, Chris, Supersheds: The Architecture of Long-Span, Large-Volume Buildings, Boston: Butterworth, 1996

Yeomans, David T., The Trussed Roof: Its History and Development, Hants, England: Scolar Press, 1992

Posted on web May 30, 2003; last updated Jan. 23, 2008 [minor re-formatting]