contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 5 |

6. MOVEMENT, ORIENTATION, ACCESS

A short digression on Cornell's gorges

OMA's stated desire, as mentioned earlier, was to connect the college's buildings. "Where a car park once stood between Sibley and Rand, a contiguous, multi-layer system of buildings and plazas unites the disparate elements of the AAP, creating a public space adjacent to the campus's most beautiful feature, just to the north—the Fall Creek Gorge."1

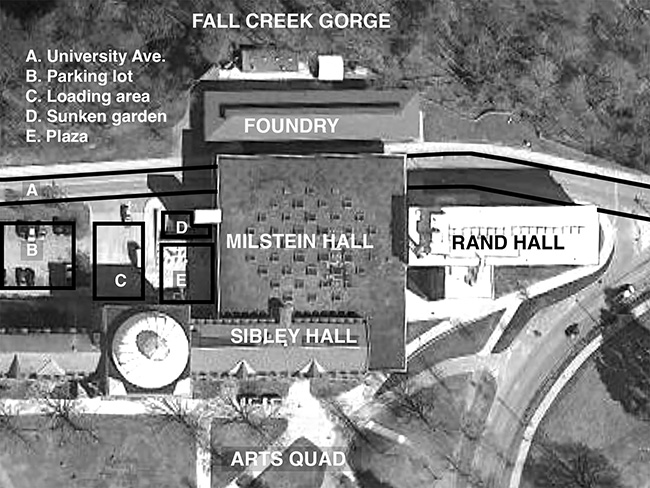

The idea that Milstein Hall created a public space ("plaza") adjacent to the Fall Creek Gorge is misleading on several counts and requires a short digression. First, the plaza is adjacent to four things on its four sides, but none of those things is the Fall Creek Gorge. As can be seen in the annotated Google Map satellite image (fig. 6.1), the plaza—labeled "E"—is actually adjacent to the following spaces: Sibley Hall to the south; a loading dock and parking lot to the west; a sunken garden and University Avenue to the north; and Milstein Hall to the east. Fall Creek does indeed exist north of University Avenue, but there is no functional connection between Fall Creek and Milstein Hall's plaza (fig. 6.2).

Second, the idea of making visual or conceptual connections to the Gorge is a tired trope having little if any value. As I argued in a blog post from 2013:

It's both a bit weird, but also quite expected, to see the same design tropes appearing over and over again within the same time period at the same place. I hinted at this phenomenon in my 2009 song, "Prisoner of Art."2

Two examples from the Cornell campus follow. The first is based on the idea that, because Cornell is situated between two gorges, the idea of the gorge should somehow be expressed in new campus construction. So not only do we get the West Campus dorms designed by Kieran Timberlake referencing the glacial topography of the Finger Lakes, but also more literal representations of the gorges in Bailey Plaza (Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates: "A tilted, striated bluestone fountain presents a mysterious dark pool at its base, making material reference to Ithaca's famous gorges") and the Pew Engineering Quad (EDAW, Inc.: "The created landscape will dramatize the topography by adding landscaped slopes that recall the natural character of the nearby Cascadilla Gorge").3

Figure 6.1. Milstein's "plaza" in relation to the Fall Creek Gorge.

Figure 6.2. Milstein's plaza has no functional connection to Fall Creek Gorge, but rather sits awkwardly on the edge of a sunken garden and stair tower (right) with a loading area and parking lot to the west (left).

All such architectural or landscape instances of this trope miss the essential nature of Cornell's unique siting. Fall Creek and Cascadilla Gorges are natural barriers that separate Cornell from adjacent commercial and residential areas. As such, they create a "protected" zone for academic life, irrespective of their spectacular natural features, i.e., the trails, waterfalls, flora, fauna, and the characteristic siltstones, sandstones, and shales that define their steep rocky walls. But those natural features of the gorge do not themselves factor into the academic life that they bracket and contain. Rather, the protected and isolated "ivory tower" draws upon the conventions of traditional campus design, especially the quadrangles traversed by functional paths and bounded by understated brick or stone buildings; the quads serve as both circulation and gathering points for faculty and students. Kermit Parsons, former dean of Cornell's College of Architecture, Art and Planning, argued that views of the Cayuga Lake valley from traditional academic quadrangles were the primary site planning considerations of the founders, rather than connections with the two gorges: "Ezra Cornell wanted as many durable, useful buildings as he could get. He wanted to make it possible for Cornellians to survey the sweeping landscape of the Cayuga Lake valley, and he wanted the town to see University buildings on the hill against the skyline. Andrew D. White, though he was a scholarly revolutionist in most matters of higher education, admired the traditional ordered beauty of collegiate quadrangles."4

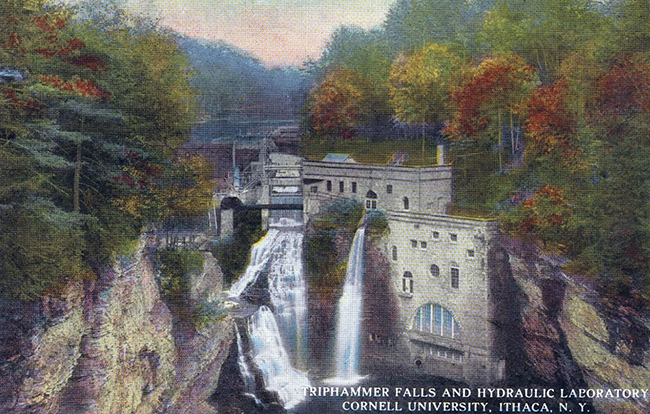

Such an academic vision, however clichéd, neither requires nor benefits from the literal intrusion of the gorges' natural features. These natural features, if brought literally or even metaphorically into the campus, would only distract from the academic tasks at hand and contravene the vision cultivated by the original campus designers. The gorges were, and are, certainly appreciated as natural attractions, but their utilitarian function— providing water power for nineteenth-century mills and hydraulic investigations—was more relevant (fig. 6.3).

Figure 6.3. The gorges bounding Cornell were appreciated as scenic attractions, but their utilitarian aspect, providing power for mills and water for hydraulic experiments—the Hydraulic Laboratory in Fall Creek from around 1898 is shown here—was more important for early campus planning. Tragically, this amazing structure was allowed to decay and collapsed in 2009.

When Ezra Cornell "worked as the manager, mechanic, and millwright at Colonel Jeremiah Beebe's mills at the foot of Ithaca Falls, he superintended the blasting of a long tunnel through the rock wall of the gorge to tap the water power of Fall Creek, and he built a stone dam at Triphammer Falls to conserve the Creek's water supply. He had built sawmills, and now he built machinery, workshops, and several houses, including his own, near the mills."5

Third, the idea that architecture or landscape ought to serve as an icon—a facile didactic signifier of some nearby and notable environmental feature—is (and here I'm using the most charitable word possible) questionable. The main formal consequence of the two gorges that bound Cornell's main campus is their sublime and unexpected presence in the landscape. One comes upon these natural wonders by crossing them (to enter or leave campus) or by descending into them (on various trails). It is precisely the contrast between the normative landscape of the adjacent campus/city and the gorges' dramatic rifts within that landscape that makes the experience so special. Abstracting and replicating the form of the gorge within the adjacent context only serves to trivialize this experience.

Fourth, the very idea of establishing some sort of public zone on the service side of Sibley Hall is flawed. Campus academic life is organized around the Arts Quad; Cornell's main buildings for the College of Architecture, Art and Planning are fortunate to have prime real estate fronting on this quad. The traditional campus buildings on the Arts Quad have a public face (on the quad) and a backside for servicing. This creates an appropriate and useful density of students and faculty on the Arts Quad, as well as optimal conditions on the quad for orientation, circulation, and causal leisure activities where one can watch and be watched. It also maintains the class-based distinction between a pedestrian-only enclave for elite student and faculty interactions versus the required servicing of this enterprise with cars, parking lots, trucks, dumpsters, and so on. Reducing the density and intensity of the pedestrian-only activities by creating a rival entrance and plaza away from the quad is therefore counterproductive from two standpoints. First, it damages the traditional quad by removing desired activity and circulation. Second, the new node of activity and circulation that has been placed away from the quad becomes dysfunctional in two ways: it mimics the form of an active gathering and circulation space associated with a real plaza without providing the necessary density of people to make the plaza "work"; and it places any student-faculty activity in the plaza side by side with the "back-door" requirements of servicing, thereby compromising the carefully cultivated image of Ivy League campus life.

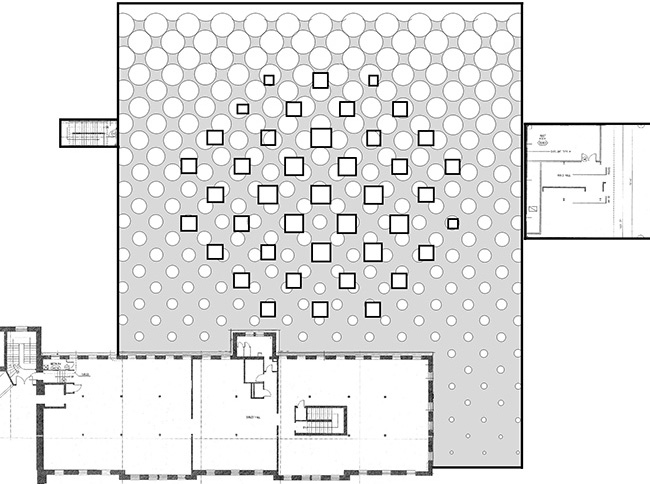

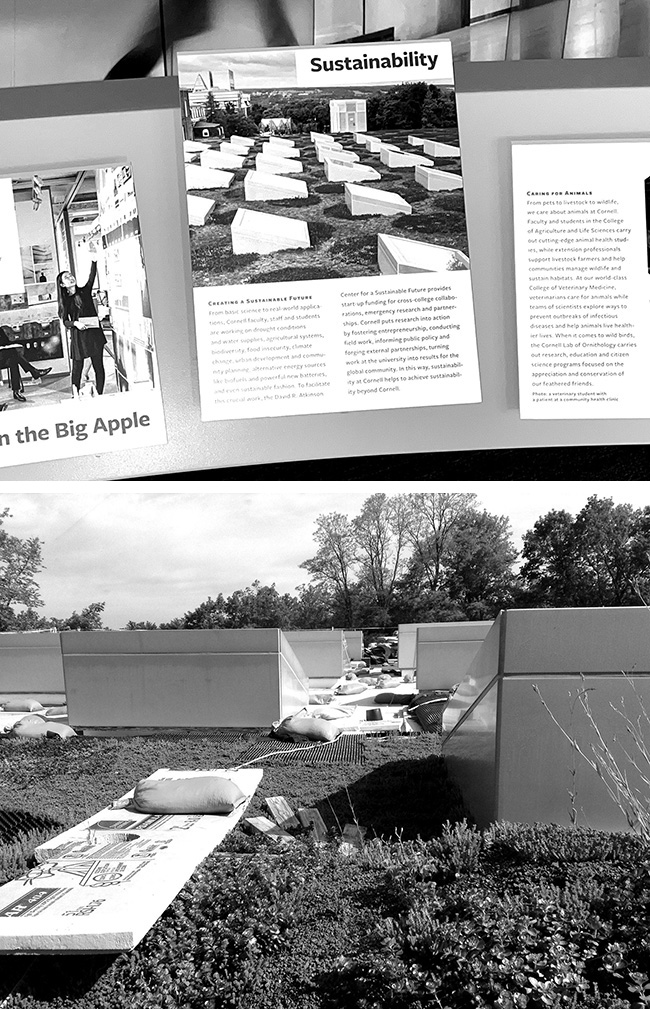

The tired trope of Cornell's Fall Creek Gorge shows up not only in the "public plaza" placed on the service side of Sibley Hall—this can at least be explained by the donor's presumed desire to give the Milstein Hall addition not only its own name but also its own identity—but also in the inane arrangement of colored sedums planted on Milstein Hall's green roof: "The entire roof, with the exception of the skylights, is vegetated in a graphic pattern of two types of sedum plantings. The sedum 'dots' gradually increase in diameter as they approach the gorge, creating a landscape that is orderly and structured nearest the Arts Quad, and a denser, less structured field as it reaches the gorge."6 First, it was quite clear when this idea was first revealed that any such arrangement of colored sedums would be transformed over time into an entirely random pattern, given the vicissitudes of natural vegetative processes and the necessity of constant roof repair. With close to 24,000 individual sedum plants initially planted by hand in the colored pattern described above (fig. 6.4), there was never going to be a maintenance budget large enough to continually restore that pattern as it was inevitably compromised over time.

Figure 6.4. Milstein Hall's inaccessible green roof is planted with about 24,000 sedums in two colors, with a pattern of dots that gradually increase in size toward the Fall Creek Gorge. The squares in the center of the roof are skylights.

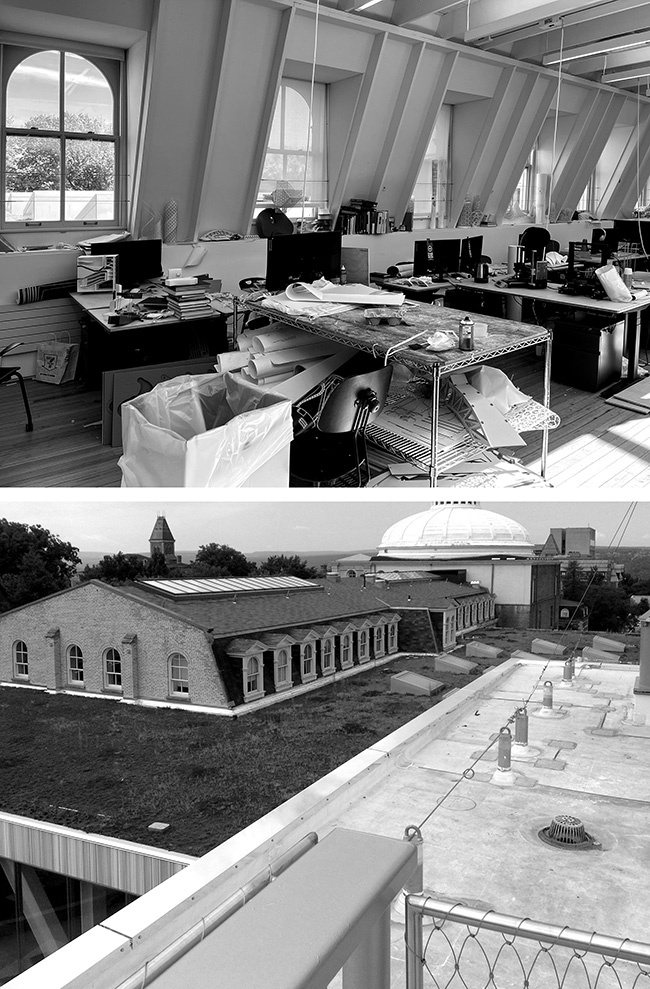

Second, the roof itself is hardly visible, except from third-floor studios in adjacent Sibley Hall and obliquely from Rand Hall's roof terrace (fig. 6.5).

Figure 6.5. Milstein Hall's green roof cannot be seen, except from the third-floor studios in Sibley Hall (top) and obliquely from a corner of the rooftop gallery in Rand Hall (bottom). What appear to be green-roof plantings visible from Sibley Hall's third-floor studios are, in reality, trees located across University Avenue on the edge of Fall Creek gorge.

Third, the roof is inaccessible, so viewing Fall Creek Gorge from the northern edge of the roof is impossible, except for maintenance workers strapped securely in place with OSHA-certified personal fall arrest systems.7 In the final analysis, Milstein Hall's vegetated roof, with its obscure reference to the "order" and "structure" of vegetation in Fall Creek Gorge versus the Arts Quad, becomes nothing more than an expensive and transient branding tool—a one-time photo op for greenwashing (fig. 6.6).

Figure 6.6. Milstein's green roof, as a branding device for "Sustainability" at Cornell's Martin Y. Tang Welcome Center (top); and as it has devolved over time (bottom).

A dysfunctional arcade

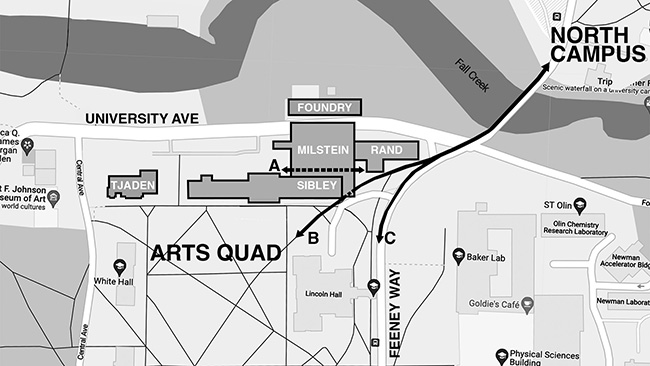

There are two primary reasons that the Duane and Dalia Stiller Arcade, located between Sibley Hall and Milstein Hall at ground level, is almost always empty. First, it doesn't provide a useful connection to anywhere in particular, so it is rarely used as a shortcut or path from somewhere to someplace else. The primary circulation paths at this end of campus—labeled "B" and "C" in figure 6.7—connect the Arts Quad (and also the rest of the campus, accessed via Feeney Way, formerly East Avenue) with undergraduate dormitories in North Campus. There is virtually no reason for anyone to circulate through the arcade, labeled "A."

Figure 6.7. Campus circulation in the vicinity of Milstein Hall: Path "A" is the Duane and Dalia Stiller Arcade; paths "B" and "C" connect North Campus dormitories with the Arts Quad and the rest of campus.

Second, it meets none of the criteria for being a successful outdoor space in its own right: it is dark and dismal, it is freezing in the winter, there is often no seating (the infantile plastic "bubbles" set into the concrete dome might work in a nursery school setting, but are inexplicable in the context of a major research university), and there is no compelling activity generated in the arcade from adjacent buildings (fig. 6.8).

Figure 6.8. The arcade in Milstein Hall, with seating bubbles visible in the background, is almost always empty.

It is instructive to compare Milstein Hall's underutilized outdoor arcade with that of Duffield Hall, a nearby and heavily used enclosed arcade that was created between two campus building on the Engineering Quad. Both Milstein Hall and Duffield Hall were additions to existing buildings and, as such, had similar design challenges in joining a new with an existing building. Zimmer Gunsul Frasca (ZGF), the architects for Duffield Hall, activated the connection to the existing building (Phillips Hall) by creating a covered arcade bounded by Phillips Hall on one side and the new Duffield Hall on the other side. In this space, they designed useful seating areas in which students can study or collaborate in relative privacy, but with visual connections back to the main circulation spine of the arcade, so that both those seated along the perimeter of the arcade and those circulating down the middle feel active and engaged. Naturally, there is also food available, and plenty of places to sit, eat, and drink (fig. 6.9).

Figure 6.9. The arcade in Duffield Hall is constantly filled with activity.

The architects for Milstein Hall, in contrast, left the arcade space between Sibley Hall and Milstein Hall unenclosed and unpleasant, with no collaborative seating, no ability to see and be seen, no compelling activities visible in the adjacent buildings, and—as a result—with no particular reason for anyone to enter (fig. 6.8). The images in figure 6.9 and figure 6.8 show the two arcades at the same time on the same day (Tuesday, March 21, 2023, at noon), but this contrast in functionality could be demonstrated on virtually any day and any time when students are on campus.

Koolhaas's "Junkspace," written just a few years before OMA began the Milstein Hall project, may provide some insight into the origin of the arcade's dysfunction, although it is risky to allege such links between the office's theory and practice. In this article, a brilliant 7,500-word rant formatted into a single, continuous paragraph, the enclosed mall (aka Junkspace) comes under withering attack:

Junkspace seems an aberration, but it is the essence, the main thing… the product of an encounter between escalator and air-conditioning, conceived in an incubator of Sheetrock (all three missing from the history books). Continuity is the essence of Junkspace; it exploits any invention that enables expansion, deploys the infrastructure of seamlessness: escalator, air-conditioning, sprinkler, fire shutter, hot-air curtain… It is always interior, so extensive that you rarely perceive limits; it promotes disorientation by any means (mirror, polish, echo)…8

This hyperbolic descriptive text soon turns into an explicitly anti-atrium warning: "Note to architects: You thought that you could ignore Junkspace, visit it surreptitiously, treat it with condescending contempt or enjoy it vicariously… […] But now your own architecture is infected, has become equally smooth, all-inclusive, continuous, warped, busy, atrium-ridden…"9 And not only that, this atrium culture fosters complacency and destroys our ability to think: "Junkspace is political. It depends on the central removal of the critical facility in the name of comfort and pleasure."10 So it's possible that this ideological posturing had some influence on the decision to leave Milstein Hall's arcade unconditioned, unenclosed, and—most importantly—without any formal or functional references to the despised prototype of the atrium/mall.

On the other hand, the danger of taking such theoretical diatribes seriously as determinants of OMA's practical design strategies can be illustrated by the following passage from the same article, where the text disparages vast open spaces, not that dissimilar to Milstein Hall's studio floor—a space with no walls, except for a shimmering, mirror-like stainless steel electrical closet enclosure, that is penetrated and supported by huge hybrid trusses:

There are no walls, only partitions, shimmering membranes frequently covered in mirror or gold. Structure groans invisibly underneath decoration, or worse, has become ornamental; small, shiny, space frames support nominal loads, or huge beams deliver cyclopic burdens to unsuspecting destinations.11

Movement versus circulation

Just as abstract programmatic adjacencies are confused with circulation systems in the design of Milstein Hall, there is also an implicit conflation of a type of performative athletic movement—whether featuring trained dancers, "free runners," or skateboarders—with the type of movement in and around buildings that constitutes useful circulation. As far as I know, nothing has been produced for Milstein Hall comparable to Tomas Koolhaas's video of Chris Lodge "free running" through OMA's Casa De Musica building in Porto, Portugal,12 although not for lack of trying. For example, I was told that the choreographer William Forsythe, who had accepted a prestigious Cornell position as an A.D. White Professor-at-Large, was asked to stage an avant-garde dance performance in Milstein Hall shortly after it opened, but rejected the venue, preferring instead the unpretentious industrial aesthetic of Rand Hall next door.13

There has also been a love-hate relationship with skateboarders, who—even more than Forsythe and his dancers—would show how the building encourages kinesthetic movement, while also providing some street cred. Medina Lasansky describes the "multi-sensory appeal" of Milstein Hall to practitioners of the skateboarding craft, in particular their attraction to the curved surface the of the dome with its spherical bubbles. Yet, as Lasansky points out, "the rampant skateboarding has proven irksome to the college administration. Signs have gone up in an attempt to limit the boarding and a high-level official has been spotted scrubbing scuffmarks off the 'bubble bank' … Undoubtedly there are liability concerns, and worries about the extent to which skateboarders might damage the building."14 As illustrated in figure 6.10, skateboarders are indeed attracted to the building's curved and sloping surfaces, in spite of warning signs (which were put in place shortly after the building opened but then removed) and damage to the building itself (I can't confirm that the broken glass and light fixture were caused by skateboarders, but it seems likely).

Figure 6.10. Skateboarders are warned away from Milstein Hall's dome (top left) but show up anyway (top right); lighting fixtures and glazing panels have been damaged (bottom left and right), possibly from collisions with skateboards.

Orientation, and signage

Circulation presupposes orientation, and orientation can be enhanced both by signage as well as by the clarity and coherence of the building's circulation system. In general, orientation is facilitated by hierarchical elements (major circulation axes, or open atriums) which provide easy-to-read clues relating where one is to where one was and where one wants to be. In contrast, buildings with a maze of corridors, or multiple symmetries that confuse front-back or side-to-side relationships, make it easy to get lost—disoriented—in a building.

Milstein Hall's connection to Sibley Hall and Rand Hall, according to OMA, was intended to remedy a problem of spatial incoherence in the college's existing buildings caused by "linear, corridor-based buildings that segregate the AAP's disciplines in closed rooms behind a labyrinth of entrances, security codes and dead ends."15 In fact, the opposite is true. Before Milstein Hall was constructed, circulation into and within the four existing college buildings was absolutely straightforward and clear: Tjaden, Sibley, and Rand Halls each had main entry doors facing the Arts Quad (Tjaden and Sibley Halls) or the main circulation path connecting the Arts Quad to North Campus (Rand Hall); while each of these buildings had secondary service entrances facing University Avenue. The Foundry, "originally designed as a blacksmith shop in the 1860s by Charles Babcock, the first professor of architecture at Cornell,"16 was always isolated from the main campus buildings surrounding the Arts Quad, and remains so, even after the addition of Milstein Hall.

With the addition of Milstein Hall, circulation into and within the college buildings became much more confusing. First, connections between all three of the interconnected buildings happen only at the second floor, and—as argued above—there is no coherent system of circulation at that level, but instead only a diagram of abstract adjacencies that actually inhibits circulation. Second, even if the three buildings were linked at the second floor with a coherent and articulated circulation system, there is no appropriately designed connection of such a system to the first-floor entrances of Sibley and Rand Hall. Third, the multiple entries and exits for Milstein Hall's auditorium create a truly labyrinthian circulation system that is confusing even to seasoned users of the space. All in all, the auditorium has six entrances at three levels, none of which appear to be hierarchically more important than the others—in other words, there is no apparent main entrance to the auditorium. Of the six doors, three are required fire exits, so their doors swing outward from inside the auditorium space, as is required. Unfortunately, the other doors either swing inward, or slide horizontally, which could create a life-safety problem in the event of a fire, even though it is technically legal to have "extra" doors not designated as fire exits. The only interior connection from Sibley Hall to the auditorium in Milstein Hall, without going through the second-floor design studios, is through the basement. From Rand Hall, which has no basement, the only interior connection is at the second floor, through the Fine Arts Library in Rand Hall and the design studios in Milstein Hall.

Circulation systems can be so complex that movement and orientation require a comprehensive system of signs. In some cases, e.g., in the Port Authority Bus Terminal in New York City, signs are needed to compensate for an otherwise incoherent system of circulation. In other cases, e.g., in Grand Central Terminal in New York City, signs are needed even when the system of circulation is coherent and memorable, simply because there are so many interconnected activities and destinations: surrounding streets, ticket machines, train tracks, subways, stores, restaurants, bathrooms, and so on (fig. 6.11).

Figure 6.11. Signs are needed in Grand Central Terminal (left) and at the Port Authority Bus Terminal (right), both in New York City.

Milstein Hall has a system of signage to direct people both to the adjacent connected buildings and to internal programmed spaces like the auditorium and gallery. These signs were subcontracted to 2x4, a "global design consultancy headquartered in New York City," whose mission is to "identify and clarify core institutional values and create innovative, experiential, participatory and visually-dynamic ways to engage key audiences worldwide."17 Given this mission, one can only wonder how the college's "core institutional values" were translated into floor-mounted signs torched directly onto Milstein Hall's concrete floors, where they are stepped on, abused by cleaning protocols, and—as a result, in many instances—damaged or destroyed (fig. 6.12).

Figure 6.12. Milstein Hall's signage system is assembled with individual letters and symbols that are placed on the concrete slab (top-left), torched onto the concrete surface (top right), and then left to be damaged or destroyed by foot traffic and cleaning protocols (bottom left and right).

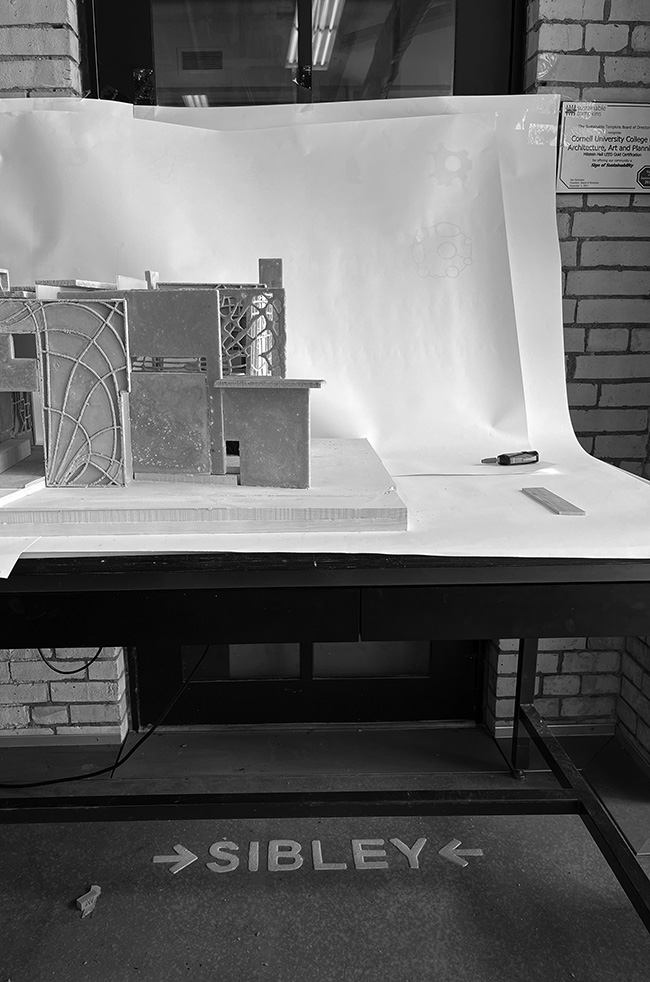

The permanence of these torched-on letters becomes particularly absurd in the context of Sibley Hall's locked doors (fig. 6.13).

Figure 6.13. Torched-on directional signs point to a permanently locked door to Sibley Hall.

Front and back: formal and service systems

Circulation systems have a political content, to the extent that they are designed to separate various classes of people, both to facilitate the utilitarian functionality that such class-based separation entails, and also to express the ideals embedded in this type of separation. Examples can be found at the urban scale as well as within individual buildings.

At the urban scale, the separation of circulation systems shows up, of course, in the purely functional differentiation between incompatible modes of transport: sidewalks for pedestrians; streets for cars, taxis, buses, trucks, service vehicles, and bicycles (if they have not been provided with separate paths); rails for trains and streetcars; helipads, airports, and so on. But there is also a political and ideological type of separation in which we find circulation systems that explicitly separate servicing functions from the formal public domain. Mews and other types of back alleys are organized to the side of, or more commonly behind, public entrances so that the class-differentiated functions of servicing—garbage collection, recycling, maintenance, storage, and so on—can operate out of sight. Similar "front-back" separations of services (in the back) from public circulation (in the front) occur in many commercial buildings as well, so that the ideal image of public space is not compromised by the reality of trash storage, loading docks, and similar things.

Where urban street plans have been organized so that this type of back alley is not possible, separation can be organized on a temporal basis, with deliveries and garbage pickup scheduled for early mornings, before the public commercial business gets started. And where incremental growth, or changes in function over time, make it impossible to physically or temporally separate ceremonial, public circulation space from utilitarian, service-type circulation, we see awkward juxtapositions of public entrances and loading docks; front doors and trash barrels.

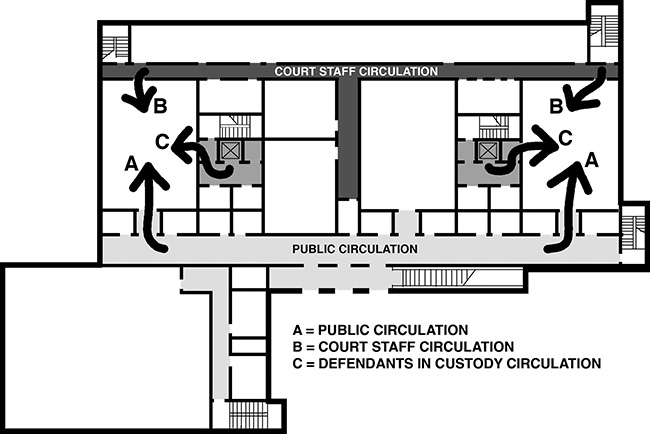

The same types of issues appear in individual buildings, for example with separate and isolated circulation zones for servants working, or sometimes living, in upscale residences—often connected with apartment kitchens. This explicit separation of public and service circulation also shows up in restaurants, shops, supermarkets, and shopping malls. At times, the separation of circulation becomes even more specialized, for example, in the design of modern courthouses, where a tripartite circulation scheme is often required to separate public visitors, court staff, and criminal defendants (fig. 6.14).

Figure 6.14. Courthouse circulation systems: public, court staff, and defendants in custody each have their own separate and distinct circulation system, all leading to the various courtrooms as shown by the arrows.

The separation of circulation systems into distinct pathways for menial workers and ordinary citizens (or into pathways for visitors, criminals, and judges) may appear natural, sensible, and even inevitable, yet it presupposes a social organization in which not only are classes of people differentiated from each other, but also in which a social ideal—often implemented on the basis of racial or religious differences, but in any case abstracted from the low-wage activities that allow the system to function—is expressed.

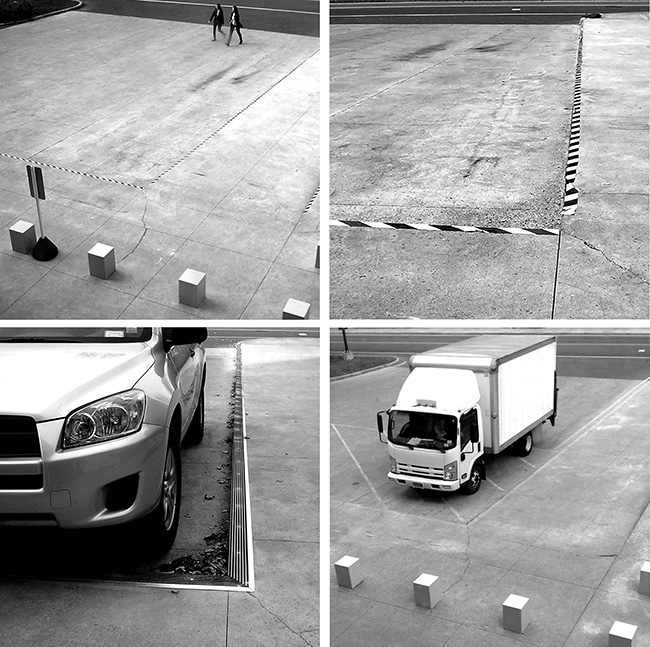

With the construction of Milstein Hall, what had been a clear separation between front and back—i.e., between formal versus service zones—has become muddled and dysfunctional. The plaza constructed on the back side of Milstein Hall, with no connection to the Arts Quad, is hopelessly compromised by its adjacency to a loading area and parking lot. Even adorned with concrete seating elements (and later with the addition of a food truck and several Jason Seley sculptures18), the space cannot overcome the same problems that compromise the arcade: it is often in shadow (being on the north side of Sibley Hall and the west side of Milstein Hall), and "people watching" is not possible since people use neither University Avenue nor the arcade as primary circulation paths (fig. 6.15).

Figure 6.15. Milstein Hall's plaza, north of Sibley Hall, has gained some lunchtime activity with the addition of sculpture, food truck, tables, and chairs that were not part of the original design; but even with these added elements and its proximity to the arcade, the plaza remains hopelessly compromised by being isolated from activity on the Arts Quad, being often in shadow, and being adjacent to a loading area, parking lot, and University Avenue.

Discontinuities: single steps and curbs

The curb separating Milstein Hall's plaza from the adjacent loading area was intended to create a discontinuity in an otherwise continuous concrete slab. Unfortunately, the lack of any further articulation of the curb edge—an articulation ordinarily created by the use of contrasting curb materials, or by contrasting concretes (asphaltic- and Portland cement-based) for the upper and lower paved surfaces, or by the use of grass or stone strips separating the upper pavement from the curb edge—makes the vertical discontinuity difficult to see and, as a result, creates a tripping hazard at the curb edge. This is especially true in the late afternoon and evening when western sunlight hits the vertical face of the curb directly and no shadows are cast that would otherwise help define a more visible boundary (fig. 6.16).

Figure 6.16. The discontinuity of Milstein Hall's plaza and the loading area, even with the addition of tactile circular discs, is extremely hard to pick up, especially in the late afternoon or early evening when there are no shadows cast by the western sun.

Temporary yellow safety tape was eventually applied to the curb edge, and this expedient was soon after replaced with a metal curb edge that provided some functional differentiation between the upper and lower concrete pavements. Inexplicably, that protection was later removed, so that the curb—at this writing—remains problematic (fig. 6.17).

Figure 6.17. After a curb with no articulation was constructed at the loading dock for Milstein Hall, temporary yellow warning tape (top left and top right) was placed over the "invisible" edge; later a textured metal curb cover (bottom left) was installed, but later removed, so that the current condition as of this writing (bottom right) has the same lack of articulation as the original.

While this particular curb condition was configured in a functionally unsafe manner, building codes offer only indirect guidance for such curb design. Single steps along egress paths are explicitly forbidden, since they "may not be readily apparent during normal use or emergency egress and are considered to present a potential tripping hazard," but a curb in this context does not constitute a "step" within a means of egress. Even so, the logic underlying the prohibition of single steps is applicable to this curb condition, and architects familiar with egress requirements and their rationale would be more likely to avoid such errors.

Instead of single steps within a means of egress, the International Building Code Commentary recommends that a ramp be used whose presence is "readily apparent from the directions from which it is approached. Handrails are one method of identifying the ramp's change in elevation. In lieu of handrails, the surface of the ramp must be finished with materials that visually contrast with the surrounding floor surfaces. The walking surface of the ramp should contrast both visually and physically."19

The code requirement to use a ramp rather than a single step was not followed by the architects of Milstein Hall at a pedestrian passage between Rand Hall and Milstein Hall along University Avenue. Even though this single step is outside Milstein Hall proper, it is still within the building's means of egress, since the means of egress includes the so-called exit discharge between the main entrance to Milstein Hall (which is also an exit) and the so-called public way (which, in this context, is University Avenue). An exception to this rule for single risers "at locations not required to be accessible" does not apply because this single stair links the main entrance to Milstein Hall (and its auditorium) to public transportation stops on University Avenue and therefore constitutes an "accessible route."20

But the point is not whether the fine print in the building code does or does not prohibit single steps in this context. The question is why an architect—unconstrained, for example, by difficult existing conditions in which non-accessible and relatively dangerous details are impossible to avoid—would purposely design such a condition. As shown in fig. 6.18, the single step (left actual as-built image) could easily have been replaced with a continuous ramp (right, photoshopped image).

Figure 6.18. The single step at the end of a ramp leading from the Main entrance (exit) from Milstein Hall to University Avenue represents a noncompliant elevation change (left, as-built image); simply extending the ramp to the University Avenue sidewalk would have eliminated that problem (right, photoshopped image).

Accessible paths

Many aspects of accessibility have become second nature for architects after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990 made them requirements for all commercial and institutional buildings. Things like necessary turning radii for wheelchairs, ramps, and elevators are routinely provided for in new construction, even if "mainstreaming"—the idea that people with disabilities should not be singled out by creating a building with, for example, monumental stairs in the front and a "handicapped entrance" around the back—still has a ways to go. However, as I have written previously:

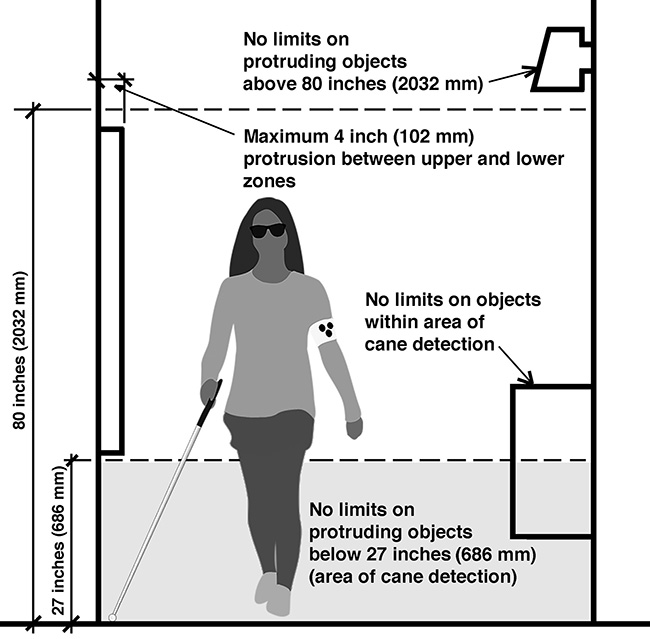

One element in the standards—created to accommodate people with vision disabilities—remains widely misunderstood and ignored: constraints placed on protruding objects, that is, objects that extend ("protrude") into circulation paths in such a way that they cannot be detected by people with vision disabilities and thus present a hazard … This issue has become increasingly important as works of architecture manifest non-orthogonal geometries in which elements, designed to challenge the orthodoxy of traditional vertical or horizontal surfaces, extend into circulation paths above the cane-sweep zone used by vision-impaired individuals to maneuver safely through the built environment. 21

There are numerous instances in Milstein Hall where sloping structural elements, fenestration, and even works of art create protruding objects within the path of egress. The 2002 New York State Building Code regulates protruding objects, not in its "Accessibility" section, but in its section on "Means of egress," requiring a "minimum headroom of 80 inches (2032 mm)" and the provision of a barrier whose leading edge is at most 27 inches (686 mm) above the floor in cases "where the vertical clearance is less than 80 inches (2032 mm) high."22 The federal Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) clarifies that any protruding object that is neither within the cane sweep zone—from the floor to a point 27 inches (686 mm) above the floor—nor higher than 80 inches (686 mm) cannot protrude more than 4 inches (100 mm), as illustrated in figure 6.19.23

Figure 6.19. Graphic illustration showing limits of protruding objects.

Although the building code prohibits protruding objects only in means of egress, the term "means of egress" is defined in the code as a "continuous and unobstructed path of vertical and horizontal egress travel from any occupied point in a building or structure to a public way,"24 so pretty much all walking surfaces inside and outside of Milstein Hall must comply. The United States Access Board guidelines on protruding objects, referencing the ADA, make it clear that these requirements "apply to all circulation paths and are not limited to accessible routes. Circulation paths include interior and exterior walks, paths, hallways, courtyards, elevators, platform lifts, ramps, stairways, and landings."25 Numerous instances of noncompliant protruding objects can be found throughout Milstein Hall. Some examples follow:

Milstein Hall's hybrid trusses consist of inclined steel elements that protrude into the circulation path. Some of these protruding structural elements are "protected" by cane-detection guards—painted steel assemblages resembling wire-frame renderings of rectangular solids— that are permanently anchored into the floor slab (fig. 6.20).

Figure 6.20. Typical cane-detection guard at inclined (protruding) structural element in Milstein Hall.

However, many other inclined structural elements in Milstein Hall are either not protected at all, or are inadequately protected (fig. 6.21).

Figure 6.21. Cane protection guards are consistently missing at inclined elements of the hybrid trusses on the second floor of Milstein Hall that are adjacent to curtain walls or, as illustrated here, are close to the brick walls of Rand and Sibley Halls (left); other inclined elements have inadequate cane-detection guards, as illustrated in this image (right) where the guard only protects people to a height of 64 inches (1626 mm) instead of the required 80 inches (2032 mm).

If it is claimed that angled structural elements along the outside edge of the second-floor plate in Milstein Hall are not in the means of egress because they form a boundary to the egress pathway, it should be noted that without a cane-detection barrier, the boundary remains invisible to those with visual impairments, and becomes especially dangerous if the room fills with smoke—precisely the reasons for requiring cane-detection boundaries around such protrusions. These protruding objects create a hazard, not just for the visually impaired, but for all building users. Everyone, at one time or another, may become distracted and unaware that they are approaching such dangerous objects within the circulation space. Smartphone texting, in particular, is a known impediment to pedestrian safety on sidewalks and roads;26 the same dangers exist for people when surfaces of buildings protrude into circulation spaces.

There are other instances where cane-detection guards were installed incorrectly, so that the protrusions they were designed to guard against still presented hazards. In some cases, the guards were cut and extended after the building was occupied so that they would provide adequate protection (fig. 6.22).

Figure 6.22. This photo, edited with Photoshop, shows how a cane-detection guard in the Crit Room needed to be cut and extended after the building was occupied.

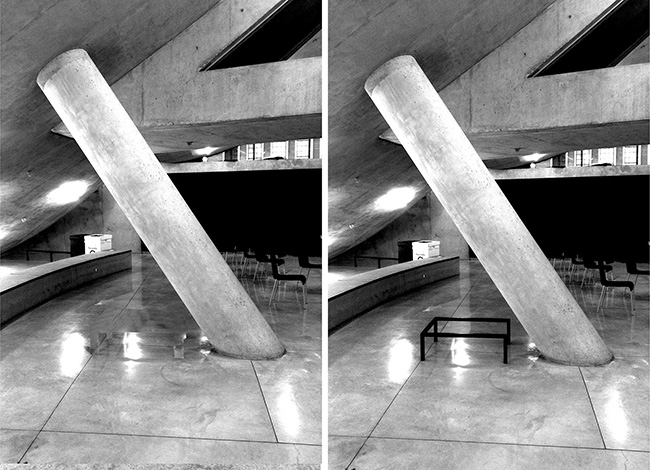

Several cane-detection guards were not specified at all, as part of the original design for Milstein Hall, but were installed after the building was built and occupied, apparently as a result of my complaints. Figure 6.23 shows how cane-detection guards were added to the sloping curtain wall in the arcade; figure 6.24 shows how cane detection guards were added to a sloping concrete column in the Crit Room.

Figure 6.23. Cane-detection guards were added to the sloping curtain wall in the arcade: before, simulated (left) and after (right).

Figure 6.24. Cane-detection guards were added to the inclined reinforced concrete column in the Crit Room: before, simulated (left) and after (right).

There are published images showing these sloping (protruding) elements before guards were installed (avant-guard?),27 but I have chosen to simulate the original conditions by editing my own "post-guard" photos, finding this photoshopping process more pleasurable than arranging permissions with the copyright holder.

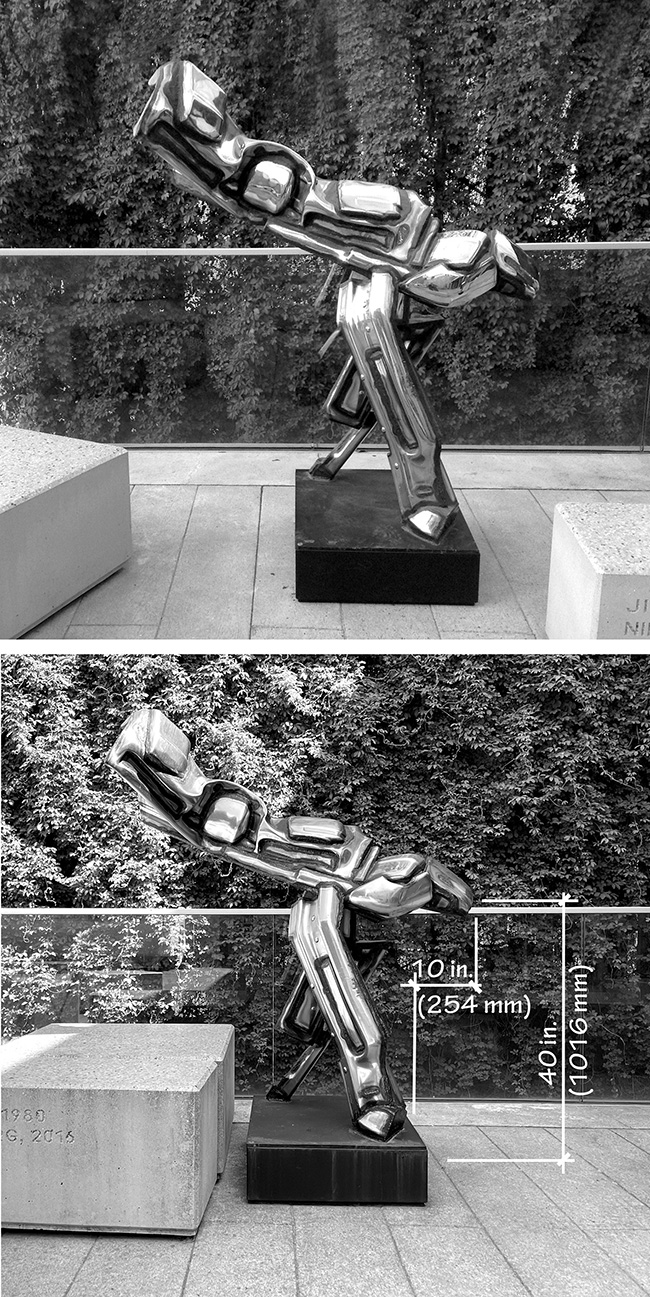

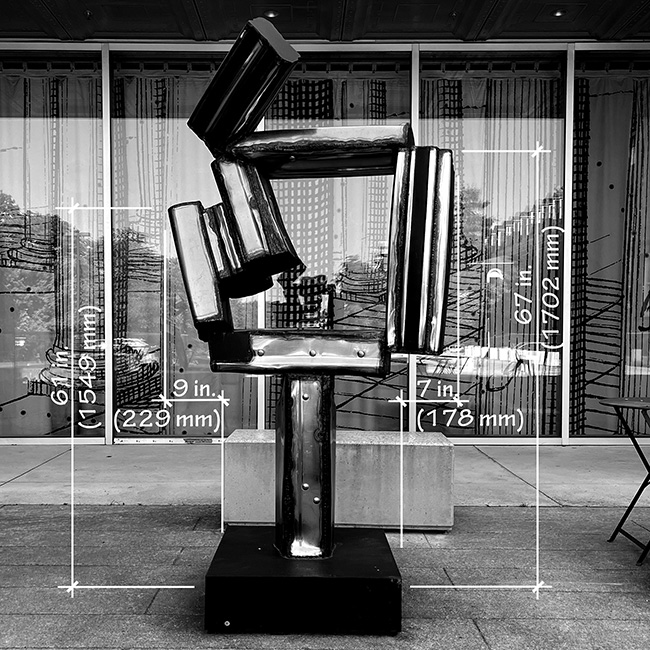

Accessibility issues involving protruding objects seem to keep popping up in Milstein Hall. Three works by the sculptor, Jason Seley, were placed in Milstein Hall's plaza in October 2017; one had a pedestal that acted as a cane-detection guard; the others did not. Eventually, concrete "benches" were moved below one of the offending sculptural protrusions after I brought the issue of ADA and code noncompliance to the attention of the college. But while this improvised cane-detection solution offered nominal protection on one side of the sculpture, the other side remains noncompliant (fig. 6.25).

Figure 6.25. Sculpture as protruding object. A sculpture by Jason Seley was placed on Milstein Hall's concrete deck, creating a protruding object hazard (top); eventually, the issue was "resolved" by moving two of the plaza's concrete benches below the protruding part of the artwork, which created a cane-detection guard on one side of the sculpture, but not on the other side (bottom), where the welded car bumpers still protrude 10 in. (254 mm) into the circulation zone.

A second Seley sculpture on the plaza is also noncompliant, with both sides protruding more than the allowable 4 inches (100 mm) beyond the pedestal (fig. 6.26).

Figure 6.26. This sculpture by Jason Seley has protruding elements in violation of the ADA and the building code.

In the same outdoor space, a food truck with dangerous and illegal protruding canopies was designed and installed after Milstein Hall was completed and occupied and, like the Jason Seley sculptures, was not part of the design brief given to OMA (fig. 6.27). Two and a half years after I complained about its ADA/code violation, Cornell finally modified the protruding canopy supports so that they would not extend beyond the 4-in. (100 mm) limit.

Figure 6.27. This sculpture by Jason Seley has protruding elements in violation of the ADA and the building code.

Notes

1 "Milstein Hall Cornell University."

2 For lyrics, music video, and other pertinent information about the author's song, "Prisoner of Art," here.

3 Jonathan Ochshorn, "Prisoner of Art (Again)," ImpatientSearch (blog), here.

4 Parsons, The Cornell Campus, 1–2.

5 Parsons, The Cornell Campus, 3.

6 "Milstein Hall's Innovative Design."

7 The requirement for workers to be strapped in makes routine maintenance of the vegetated roof cumbersome and expensive. There is no permanent guard rail at the roof perimeter that would have allowed maintenance workers free access; instead the architects disingenuously (and inaccurately) claim ease of maintenance on the basis of a required access stair: "On the west side of Milstein Hall an ivy-covered, open-air metal clad stair tower contrasts the long horizontal upper plate. The stair tower connects all levels of Milstein Hall and provides access to the green roof for ease of maintenance." "Milstein Hall's Innovative Design Cornell" (my italics).

8 Koolhaas, "Junkspace," 175.

9 Koolhaas, "Junkspace," 182.

10 Koolhaas, "Junkspace," 183.

11 Koolhaas, "Junkspace," 176.

12 Tomas Koolhaas, "Official trailer for 'Rem' Documentary," 2014, accessed April 18, 2023, here.

13 The director of Forsythe Productions GmbH confirmed this in an email to the author dated Sept. 25, 2023: "Having spoken with William Forsythe, since this was before my time working with him, he thought that the Rand Hall was more appropriate for the work that was being presented." Information on the performance itself can be found at Daniel Aloi, "Choreographer William Forsythe to visit, present new work in a Cornell space," Cornell Chronicle (March 1, 2012), here.

14 Lasansky, "Sensationalizing OMA's Milstein Hall," 104.

15 "Milstein Hall Cornell University."

16 "The future of The Foundry," Cornell Chronicle, February 10, 2023, here.

17 "About," 2x4, accessed April 18, 2023, here.

18 Undoubtedly related to Cornell's acquisition of these sculptures by the late professor Jason Seely, the plaza has been rebranded as the "Jason and Clara Seley sculpture court."

19 ICC, Code and Commentary, 10–8 (my italics).

20 Definitions and rules about means of egress, exit discharge, accessible routes, and elevation change (i.e., single steps) are taken from ICC, New York State Building Code, (2020). A means of egress includes the exit discharge, which is "that portion of a means of egress system between the termination of an exit and a public way" (Definitions, chapter 2); a public way is "a street, alley or other parcel of land open to the outside leading to a street, that has been deeded, dedicated or otherwise permanently appropriated to the public for public use and which has as a clear width and height of not less than 10 feet (3048 mm)" (Definitions, chapter 2). Regarding single steps: "Where changes in elevation of less than 12 inches (305 mm) exist in the means of egress, sloped surfaces shall be used. Where the slope is greater than one unit vertical in 20 units horizontal (5-percent slope), ramps complying with Section 1012 shall be used. Where the difference in elevation is 6 inches (152 mm) or less, the ramp shall be equipped with either handrails or floor finish materials that contrast with adjacent floor finish materials." There is an exception for single risers "at locations not required to be accessible by chapter 11" ("1003.5 Elevation change"). However, this location in Milstein Hall is required to be accessible since it connects Milstein Hall's main entrance (and its auditorium) to public transportation stops and therefore qualifies as a required "accessible route" ("1104.1 Site arrival points").

21 Ochshorn, Building Bad, 44–45.

22 ICC, "1003.2.5 Protruding objects," New York State Building Code, 2002, 202–203.

23 "Protruding Objects," Guide to the ADA Accessibility Standards, accessed June 3, 2023, here.

24 "Definitions," ICC, Building Code of New York State, 2020 (my italics).

25 "Protruding Objects," Guide to the ADA Accessibility Standards.

26 "Smartphone texting linked to compromised pedestrian safety," ScienceDaily, Feb. 3, 2020, accessed March 19, 2023, here.

27 For photos of Milstein Hall by Matthew Carbone, showing various protruding elements without cane-detection guards, see "Milstein Hall at Cornell University / OMA."

contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 5 |