contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 4 |

5. CIRCULATION

General principles

Circulation—describing the movement of people in, outside, and between buildings—is central to both function and flexibility. In the built environment that exists outside of buildings, an array of connected streets, sidewalks, plazas, and similar pathways are most often established in the public rights-of-way that simultaneously define the boundaries of privately or publicly owned parcels of land while enabling the unfettered movement of people, goods, and services between these parcels. Within buildings themselves, circulation facilitates the movement of people horizontally on any floor level through lobbies, corridors, hallways, aisles, or rooms that enable access to all the functionally separated spaces or rooms on that floor; and vertically between all floor levels, using stairs, elevators, ramps, and escalators. A system of emergency exits and exit access (parts of the means of egress) is a specialized form of horizontal and vertical circulation designed for fire safety that may utilize the building's normal circulation routes or rely, in part, on specially designated emergency-only routes, sometimes protected with fire-resistance-rated enclosures.

A key characteristic of circulation systems in buildings is that they function analogously to the rights-of-way that legally define circulation zones outside of privately held parcels of property on which buildings are built. The status of rights-of-way as public zones, permanently available for free passage, is fundamental to the ability of private property to function. Clearly, if the public right-of-way was controlled privately and speculatively, i.e., organized for the advantage of its owners, the entire system of private property—relying on unfettered circulation systems to gain access to the world of goods and services, and vice versa—would cease to exist. The public rights-of-way also benefit from being organized into a coherent system of sidewalks, roads, utilities, and various other transportation modalities that facilitates orientation and efficient movement.

In the same way, functional circulation systems in buildings have the quality of "public" zones to enable free movement of people, goods, and services among the "private" rooms and spaces in the building, and also to facilitate orientation and efficient movement. Filling a building with rooms and spaces is clearly not enough, no matter how compelling their programmatic juxtapositions and adjacencies may seem: without an independent ("public") system of circulation to which all these rooms and spaces are linked, movement within the building—between and among the rooms and spaces—is forever constrained by the requirement to move through one room to get to another.

To provide a reliable and permanent framework for movement, circulation systems in buildings—much like enclosure systems that define the outside boundary of buildings—are less likely to be moved than, for example, the nonstructural partitions that define the boundaries of individual rooms, especially in multi-story buildings. This is because the vertical circulation components—things like stairs, elevators, ramps, and escalators—cannot easily be moved once they are constructed. They rely on shafts (holes) that penetrate through floors, creating unique structural and spatial conditions that, once constructed, cannot easily be altered. Horizontal circulation systems like corridors are also relatively difficult to reconfigure once established, in part because they sometimes have special fire-resistant construction on all four surfaces (walls, floors, and ceilings) but more importantly, because they tend to be connected, ideally in a rational and efficient manner, to the fixed vertical circulation nodes on each floor. Horizontal circulation systems, and even vertical circulation, can certainly be changed to accommodate new configurations of rooms and spaces on any particular floor, but doing so is often an expensive and disruptive exercise: imagine changing the location of elevators in a multistory office building in order to make room for one large conference room on an upper floor. In general, flexibility is enhanced when the circulation system in a building is carefully configured at the outset to anticipate the types of spatial changes that might occur in the future.

Aside from inadequate means of egress for the Crit Room, discussed in chapter 16, general circulation systems in Milstein Hall contradict these fundamental principles in numerous ways.

Compromised right-of-way

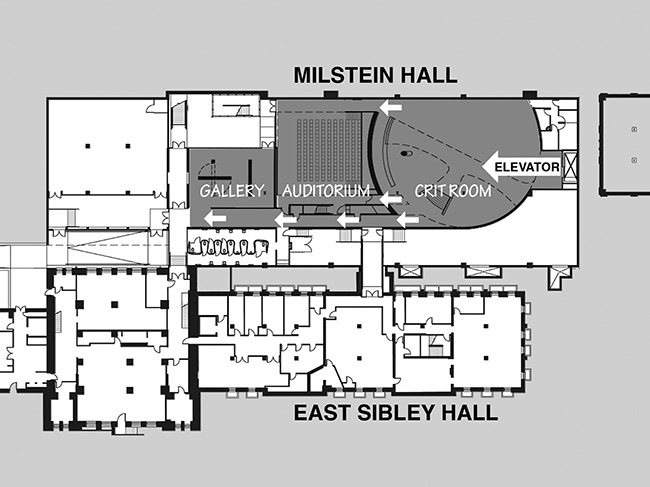

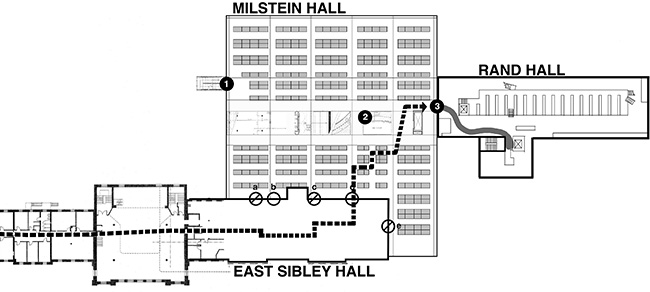

Milstein Hall's circulation system violates the essential requirement of acting as a "right-of-way" to provide "public" access to all the various rooms and spaces in the building. This is true not only because the entry-lobby-bridge has no visual or acoustic separation from studio and Crit Room spaces above and below, but, more fundamentally, because Milstein Hall's glass elevator has been designed so that users are forced to pass through the Crit Room in order to gain access to either the auditorium or the gallery at the lower level (fig. 5.1). The middle level of the auditorium can be accessed directly from the entry-level bridge without using the elevator, but this level does not provide an accessible path to the lectern or lower-level seating. These design decisions effectively preclude having independent events occurring simultaneously in the Crit Room and either the auditorium or the gallery.

Figure 5.1. Taking the elevator to the gallery or auditorium in the basement of Milstein Hall requires passing through the Crit Room.

Second-floor circulation system

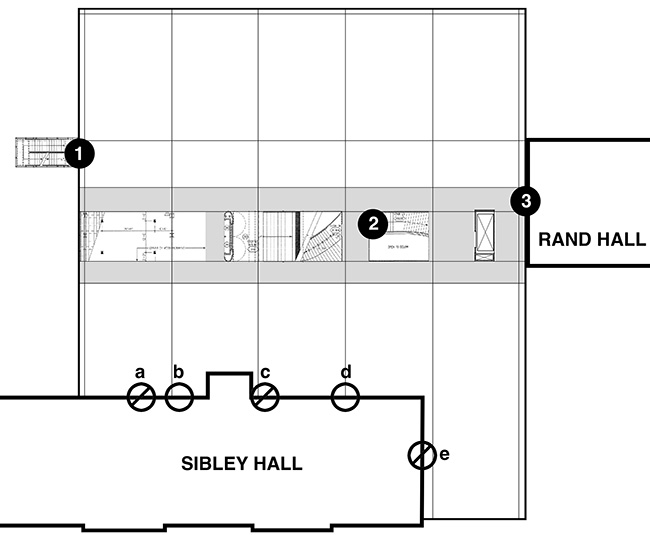

Looking only at the second-floor studio level, we see that the main horizontal circulation aisles, shown as a gray tone on either side of the interior exit access stairway labeled No. 2 in figure 5.2, are not logically connected to the outdoor vertical circulation/egress stair labeled No. 1, which is offset to the north. Because the plan is "open," without fixed horizontal hallways or corridors, it is certainly possible to get from these parallel circulation aisles to egress stair No. 1, but the connection is awkward. Moreover, the discontinuity between the main horizontal circulation path and this required fire stair would make future subdivisions of the space more difficult since some sort of formal corridor would need to be created linking the main east-west exit access to this vertical exit.

OMA, on their website, describes Milstein Hall's second-floor studio level as a "type of space currently absent from the campus: a wide-open expanse that stimulates the interaction of programs, and allows flexibility over time."1 If Milstein Hall were a stand-alone building with its second floor programmed exclusively for a vast array of studio desks—a "wide open expanse" with no privacy, acoustic separation, or individual control of lighting levels—the circulation system designated by the gray aisles in figure 5.2 would be almost adequate; Stair No. 1 still compromises the functionality of the studio desks in its vicinity since it functions as a vertical circulation node without being connected to the horizontal circulation system.

Figure 5.2. Circulation patterns on the second floor of Milstein Hall are defined by required fire exits (No. 1 is an outdoor stair; No. 2 is an open exit access stairway; and No. 3 is an exit into Rand Hall) and by five connecting doors into East Sibley Hall (a, b, c, d, and e), two of which are open (b and d), two of which are locked at all times (a and c), and one of which—on the eastern wall of Sibley—has been removed (e).

But such an arrangement is hardly flexible, unless "flexible" is taken to mean moving around studio desks within the open spaces between the columns and hybrid trusses. The type of flexibility that this arrangement does not support is the type of change typical in academic campus buildings: subdividing large spaces into smaller ones or combining small spaces into larger ones to account for changes in what programs are to be housed in the space (e.g., to accommodate art, planning, real estate, or any number of unanticipated departmental or college entities) and how existing programs are expected to operate (e.g., with drafting tables, laptops and monitors, 3-D printers, large groups, small groups, and all the variables that define desired levels of thermal, acoustic, and visual comfort and control).

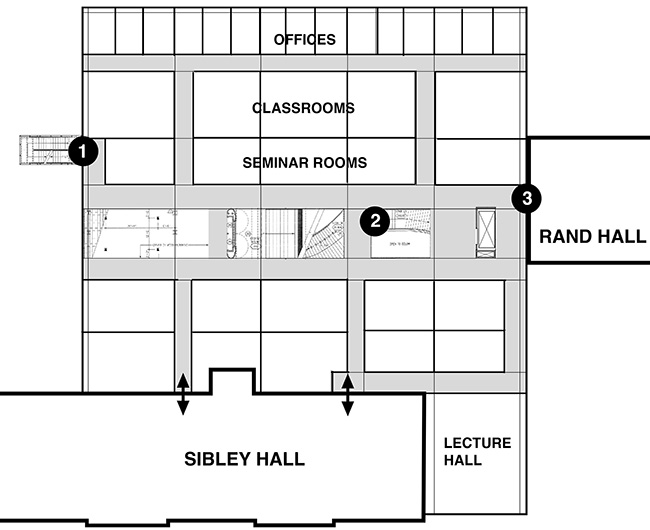

The particular geometry—the "wide open expanse"—that distinguishes Milstein Hall's second floor from typical academic building layouts makes it difficult to plan alternative arrangements of rooms within the space. For example, my schematic and unsolicited subdivision of the studio floor into offices, classrooms, seminar rooms, and lecture halls (fig. 5.3) would create many interior rooms with no windows, and a rather awkward circulation system whose constraints include the offset location of Stair No. 1, the position of existing doors into Sibley Hall, and at least three fire-safety concerns: the requirement to limit dead-end corridors to 50 feet (15 m); the requirement to limit common path of egress travel distances to 100 feet (30 m); and the need to configure large lecture rooms so that the distance between their two required exit doors is at least half the diagonal length of the room itself. Of course, other subdivisions of Milstein Hall's studio floor are possible, and might even be necessary—depending on specific programmatic needs that may arise in the future—but the basic constraints illustrated in figure 5.3 would remain.

Figure 5.3. Milstein Hall's second floor shown subdivided into offices, classrooms, etc. The three required fire exits are labeled Nos. 1, 2, and 3; existing connections into Sibley Hall are shown with double arrows.

Milstein-Sibley connection

In Milstein Hall, the proliferation of doors on the second-floor studio level within the Sibley Hall fire barrier (described in chapter 15) creates an appearance of flexibility, but, in reality, not only makes circulation between Milstein and Sibley Hall more difficult, but also makes it difficult to efficiently configure space in both buildings. A system of circulation should facilitate movement of people, goods, and services by enabling "public" access to the various "private" rooms and spaces on both sides of the fire barrier wall separating the two buildings. But rather than create such a permanent and coherent "right of way"—a true horizontal circulation system—connected to the nodes of vertical circulation in both Sibley Hall and Milstein Hall, the architects instead designed an abstract and idealized diagram of programmatic adjacencies without any consideration of the need for "public" access to the as-yet-unspecified and "private" programmatic content in both buildings.

Before Milstein Hall was constructed, the rooms in Sibley Hall were deployed on either side of a double-loaded corridor, with the potential for larger assembly spaces (e.g., lecture halls) at the ends of the building. After Milstein Hall was constructed, four connecting doors were created by enlarging window openings in Sibley Hall's brick loadbearing wall that became a fire barrier separating (and connecting) the two buildings. A fifth door was inserted in Sibley Hall's eastern wall, not simply by enlarging an existing window opening, but by removing a long section of loadbearing brick wall and replacing it with a steel beam acting as a large lintel spanning the opening. A dramatic fire-rated glass wall and door were intended for this large opening, but instead, an ordinary steel door was specified, and the remainder of the opening was unceremoniously covered up with drywall (fig. 5.4). That situation persisted for a decade or so; at the time of this writing, the door has been removed, and all evidence of its intended grandeur has been covered up entirely with fire-rated drywall. Circulation through this door has been foreclosed.

Figure 5.4. The fifth door connecting Milstein Hall and Sibley Hall was changed from a glass wall and door in Sibley Hall's eastern loadbearing wall—the opening was created at great expense to allow for this expanse of fire-rated glass—to an ordinary steel door with the adjacent space unceremoniously filled with fire-rated gypsum board. At the time of this writing, the door has been removed and the opening has been covered with fire-rated drywall.

In any case, to allow circulation through the four remaining doors connecting Sibley Hall and Milstein Hall, the rooms adjacent to these openings would need to be reconfigured as circulation space, thereby effectively destroying their utility as rooms. Initially, this problem was solved by simply locking all four doors: this was done because East Sibley Hall, at that time, was home to the Fine Arts Library and the security of books and other library materials precluded such unfettered circulation into Milstein Hall. When the library was moved into Rand Hall, it became possible to open the doors, at least until it was discovered that doing so compromised the functionality of spaces in Sibley Hall, which could not simultaneously facilitate "public" circulation between the two buildings while serving their own needs as "private" rooms. At the present time, an awkward compromise has been reached: two doors have been locked and disabled; a third door opens into a new IT support space in Sibley Hall (fig. 5.5) and a fourth door opens into a room used for trimming large-format prints (fig. 5.6).

Figure 5.5. One of the four doors linking Milstein and Sibley Halls provides access to an IT support room, visible behind the glass door (right); in Milstein Hall, the circulation aisle to this door is bisected by a row of steel columns (left).

Figure 5.6. A second unlocked door between Milstein and Sibley Halls provides access to a room used for trimming large-format prints, shown as viewed from Milstein Hall (top right) and from Sibley Hall (bottom right). The latter view shows how other potential uses such as office and classroom space are precluded by the need for spaces that can function for circulation. Both views also show that this door, a protected opening in a fire barrier that is required to be closed, has been improperly (and dangerously) propped open to facilitate access between the two buildings; the danger is heightened by the mass of combustible material left on tables and on the floor of Sibley Hall, and by the iron on the table adjacent to the door (left).

In these two latter cases, the rooms in Sibley Hall with functioning doors into Milstein Hall have effectively been turned into "servant spaces" for Milstein Hall. This is problematic for the same reason that using adjacent Rand Hall for "servant spaces"—bathrooms, egress stair, and mechanical room—is problematic: it compromises the flexibility of the "servant" buildings by assigning their spaces to Milstein Hall and it compromises the flexibility of the "served spaces" in Milstein Hall by placing required functions in adjacent buildings in ways that may constrain future renovations, upgrades, or unanticipated types of changes.

For example, the mechanical room for Milstein Hall that was placed in Rand Hall is now permanently boxed in by the Mui Ho Fine Arts Library, and cannot easily be expanded or even upgraded without affecting the adjacent library. Similarly, neither the circulation system for Sibley Hall's second floor nor the circulation system for Milstein Hall's second floor can be altered without impacting the other building. This would not be such a problem if the three conjoined buildings were actually treated as a single building and designed accordingly, but as is typical in privately endowed universities, each building maintains its own identity, especially in relation to upgrades and changes made possible by donors. Money for Milstein Hall, partially funded by a gift from the Milstein family, was restricted, in large part, to that building alone.2 Similarly, money for the Mui Ho Fine Arts Library was allocated only for Rand Hall. And when it comes time for an upgrade to East Sibley Hall, one can confidently predict that the money will be used only for East Sibley Hall.

So much for the two doors that facilitate circulation between Milstein Hall and Sibley Hall. The other two doors that are now permanently locked have created a fire safety problem—not because they are masquerading as exit doors that turn out to be locked, but because they were built with a lower fire-resistance rating than that required for the fire barrier wall in which they function as "openings." This lower fire-resistance for openings in fire barriers is permitted by building codes, but this permission is based on an assumption that such doors are functioning as doors, rather than as walls. The rationale is explained in the International Building Code Commentary as follows: "The fire protection rating required for an opening protective is generally less than the required fire resistance of the wall … This is based upon the ability of the wall to have material or a fuel package directly against the assembly while fire doors and windows are assumed to have the fuel package remote from the surface of the assembly."3 Combustible material (constituting a "fuel package") is often placed directly in front of the openings in the fire barrier separating Milstein Hall and Sibley Hall, as shown in fig. 5.7.

Figure 5.7. Combustible material placed in front of locked doors and windows in the fire barrier wall between Milstein Hall and Sibley Hall.

Enabling college-wide circulation

The design architects for Milstein Hall have characterized the building as "a connecting structure: a large elevated horizontal plate that links the second levels of Sibley and Rand Halls and cantilevers over University Avenue, reaching towards the Foundry building."4 When the college's Fine Arts Library was moved into Rand Hall from East Sibley Hall shortly after Milstein Hall was completed, the argument that Milstein Hall was a "connecting structure" became more urgent, since the departments of Art and Planning could not otherwise circulate easily into this allegedly integrated college facility. In fact, the idea of some internal college connection linking the Fine Arts Library to all the college's departments was deemed so important that the argument showed up explicitly in a "Site Narrative" prepared by the library's architect:5

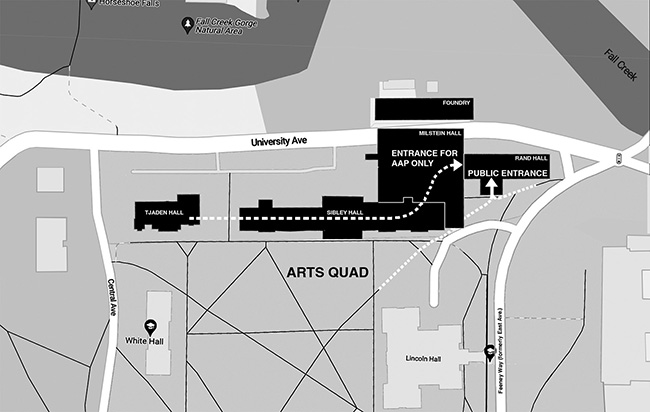

In this document, the internal college connections to the library are shown as an arrow originating in Tjaden Hall, home of the Department of Art, and then moving from west to east through the Department of City and Regional Planning in West Sibley Hall, the architecture facility in East Sibley Hall, and finally curving into Rand Hall by way of Milstein Hall (fig. 5.8). I describe the difficulty of actually maneuvering through these perimeter doors in my critique of the Fine Arts Library Site Narrative that was prepared by its architect:6

Figure 5.8. Site plan showing college buildings and purported circulation paths to the Fine Arts Library in Rand Hall.

What's peculiar about this plan diagram is the fiction that some sort of purposeful path connects the three departments of AAP (art, planning, and architecture) to the second-floor "AAP" library entrance. The … dotted line shown on the site plan, starting with Tjaden Hall (Art) on the left, actually crashes through a side wall of the art facility, not bothering with the formality of using an actual door, then enters into the basement of West Sibley Hall through a locked exit-only door, then presumably takes a stair or elevator to the second floor, where it moves through the Sibley Dome into E. Sibley, from which it enters Milstein Hall's architecture studio and finds its way into the Rand Hall library. The path through Milstein Hall is not well-defined by hallways or corridors; rather, one must figure out a way to move diagonally through the orthogonal studio layout without invading the privacy of the studio classes. In spite of all the talk about Milstein Hall being designed for the "college" and creating a "sense of connection across disciplines" ("Walkways and doorways connecting Milstein Hall to Rand and Sibley halls provide the practical advantage of moving through the college's buildings along with promoting a sense of connection across disciplines"7), it's clear that the second floor level of Milstein Hall which connects to the proposed library in Rand Hall is an architecture-only space, making it more than a bit awkward for faculty and students from the two other departments to avail themselves of this special AAP entry.

The awkward circulation from Sibley Hall, through Milstein Hall's second-floor studios, to the Fine Arts Library's "college-only" entrance is directly related to the flawed notion that abstract and schematic plan adjacencies constitute, and can be substituted for, an actual circulation system. As shown in figure 5.9, the path often taken by students and faculty coming from Tjaden Hall or West Sibley Hall (i.e., from the Departments of Art and City and Regional Planning) or even from East Sibley Hall (i.e., from the Department of Architecture) winds its way through the IT service room in Sibley Hall and then through "private" studio spaces in Milstein Hall, in order to gain access to the Fine Arts Library in Rand Hall.

Figure 5.9. Actual circulation patterns at the second-floor level, to gain access to the Fine Arts Library in Rand Hall, require maneuvering awkwardly through the IT service room in Sibley Hall and "private" studio spaces in Milstein Hall. Numbers (1–3) refer to required exits from Milstein Hall.

Parasitic use of adjacent buildings

Exit No. 3 into Rand Hall (fig. 5.9) was not originally designed as a required means of egress from the second floor of Milstein Hall, but merely as a connection from one building to the other. This changed when the occupancy numbers for Milstein's second floor were recomputed—apparently to account for the increased occupancy of assembly areas like the wood-floored "studio lounge" (fig. 5.10)—and the path of least resistance (pun intended) was to use Rand Hall's existing interior exit stairway for the additional egress capacity now required for Milstein Hall.

Figure 5.10. Milstein Hall's wood floor area counts as an assembly space.

That being said, Exit No. 3 is problematic in its own way, even though it aligns with the primary horizontal circulation aisles in Milstein Hall on either side of Stair No. 2 (fig. 5.11). Because the Rand Hall exit stair is not directly connected to Milstein Hall, but rather is in the middle of Rand Hall, users of this stair coming from Milstein Hall must circulate through the Fine Arts Library, which was placed in Rand Hall after Milstein Hall was constructed. Aside from the incompatibility of some "Milstein" activities with the library occupancy in Rand—for example, bringing architectural models or materials from the first-floor Rand Hall shop up to the second-floor Milstein Hall studios in order to avoid going outside—the library is closed each night, while Milstein studios remain open.

Figure 5.11. The main horizontal circulation aisles in Milstein Hall align with the entrance into Rand Hall, Exit No. 3, shown here at the end of the circulation aisle.

This necessitated the construction of a sliding security shutter, to create a dedicated circulation aisle separated from the rest of the library, that must be rolled into place each night when the library is closed (fig. 5.12). This security shutter also allows 24/7 access to Rand Hall's second-floor bathrooms which, like Exit No. 3, must remain open to Milstein Hall's occupants at all times since bathrooms for the studio floor were not provided in Milstein Hall itself.

Figure 5.12. Milstein Hall egress and access to bathrooms in Rand Hall through the Fine Arts Library.

In other words, the open plan for Milstein Hall's second-floor studios was created by parasitically using adjacent Rand Hall as a dumping ground for utilitarian "servant spaces" that would have threatened Milstein Hall's openness: not only bathrooms and an exit stair, but also a second mechanical equipment room for the studio floor (the lower levels of Milstein Hall are served by a mechanical room in the basement, as described in chapter 3) were assigned to Rand Hall.

Aside from the arrogance of this strategy—the sublime contours of Milstein Hall were not to be sullied by such mundane necessities as mechanical rooms, bathrooms, and egress stairs—the flexibility of both Milstein Hall and Rand Hall is seriously compromised. This became evident when Rand Hall, soon after the completion of Milstein Hall, was redesigned as the Mui Ho Fine Arts Library: on the one hand, the design of the new Fine Arts Library was constrained by the presence of Milstein Hall's mechanical room on the third floor of Rand Hall; on the other hand, the construction of the library meant that both the egress stair and second-floor bathrooms in Rand Hall—both required for the continued operation of Milstein Hall—would be inaccessible for two years.

Bathrooms and egress: a parody

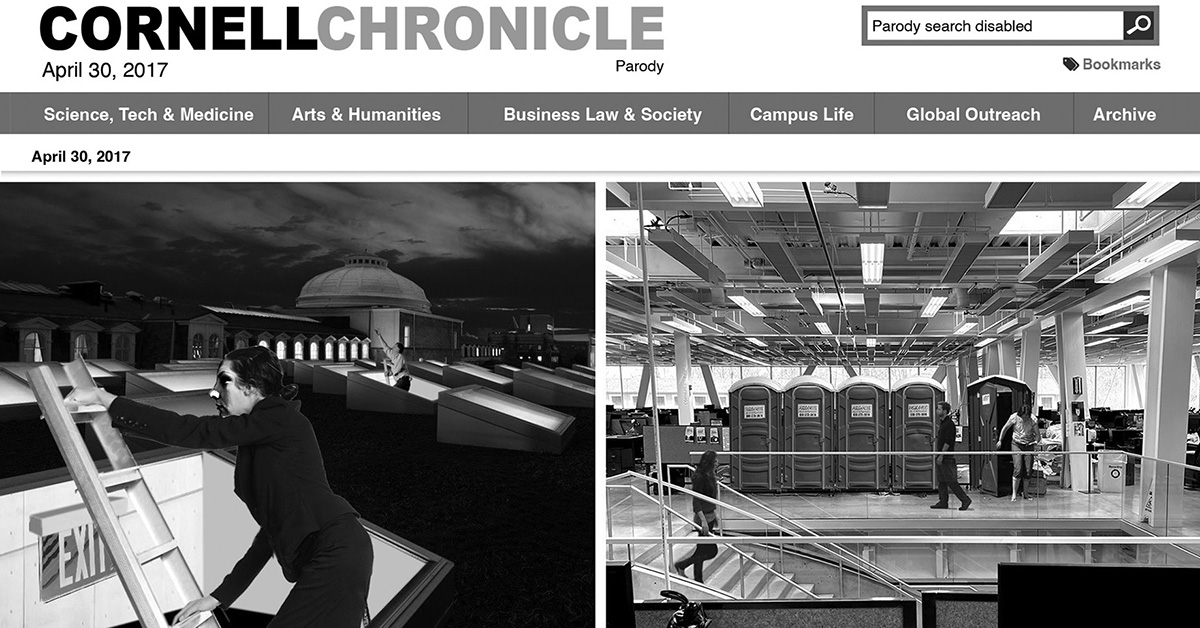

Rather than create temporary egress and bathrooms for Milstein Hall during the two-year construction period for the Mui Ho Fine Arts Library in Rand Hall, Cornell did what it does best when confronted with issues of building code noncompliance: it requested and received a code variance from New York State's Division of Code Enforcement and Administration (DCEA) to keep Milstein Hall open during the construction period, even with inadequate bathroom and exit capacity. I wrote a parody news article in 2017, reproduced below in lightly edited form. Much of the introductory text is taken verbatim from Guy Horton's "What's so Different about Koolhaas's Venice Biennale?" The photoshopped images in figure 5.13 accompanied the parody:8

Figure 5.13. Photoshopped parody images for Rem Koolhaas's proposal advocating architectural fundamentals in Milstein Hall: exits (left) and toilets (right) accompanied the parody article reproduced below.

Koolhaas proposes temporary toilets and fire exits in "flexible" Milstein Hall as Rand Hall closes for two years (parody)

When the 14th International Architecture Exhibition at the Venice Biennale, provocatively titled "Fundamentals," opened in June 2014, it was bound to produce controversy.

True to form, its director, Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, a master at harnessing the drama of the contrary, promised a Biennale quite different from those that had come before. Under his gaze, rather than spotlight the specific works of contemporary architects, his Biennale focused on larger historical dynamics, going back in time and, literally, back to the basics.

The operational theme, which Koolhaas called Elements of Architecture, covered basic, even mundane building parts like stairs and, of course, toilets. When asked by Cornell College of Architecture, Art and Planning (AAP) Dean Kent Kleinman to help with a temporary renovation of Milstein Hall—Koolhaas's signature building for AAP—he immediately agreed, seeing the project as a rare opportunity to test the conceptual framework he had proposed for Venice in a "real-life" situation.

"Because Rand Hall was parasitically used as a dumping ground for many of the nasty things—like mechanical rooms, toilets, and egress stairs—that would otherwise have diluted the conceptual clarity of the Milstein Hall design," he explained, "it is now impossible to make any alterations in Rand Hall without compromising the operation of the combined buildings." But, says Koolhaas, this was a deliberate strategy to make sure that his design would remain forever inflexible and resistant to change.

"My friend, Bill Millard," Koolhaas explained, "understood that OMA builds so-called 'ducks' to avoid the cost-cutting that inevitably threatens the aesthetic integrity of decorated sheds. Millard believes, and I agree completely, that the most striking feature of a building must now be the one that all the more mundane features require, the one whose subtraction would demolish the structure."9

Because Milstein Hall was designed, under the "Millard" doctrine, to make any subsequent changes virtually impossible, Koolhaas's current proposal cleverly invokes the newer strategy that he developed for the Venice Biennale: it goes "back to basics" with a radical scheme that brings toilet and egress capabilities into Milstein Hall itself. "This is necessary," according to AAP Dean Kleinman, "because with the construction of a new Fine Arts Library in Rand Hall, those very toilet and egress capabilities that had been parasitically placed in Rand Hall will be out of commission for at least two years."

Koolhaas justifies his new "back to basics" approach by arguing that architecture students will benefit from a process of defamiliarization in which the conventional, bourgeois concepts of "toilet" and "stair" are reframed in light of their basic, or fundamental, nature. "What is a toilet, after all?" asked Koolhaas, rhetorically. "And why does a fire stair need to always look like a conventional fire stair?" The essence of a toilet, says Koolhaas, "is just a hole in a horizontal surface with a pail to catch human excrement." And the experience of escaping from fire, he added, "will be much more primal and significant" when occupants are "forced to climb up ladders leading to Milstein Hall's green roof instead of dutifully filing down compartmentalized egress stairs like so many sheep being led to the slaughter. I doubt very much," he continued, "whether Cornell will ever want to go back to the old system once students and faculty experience the more fundamental processes that we have organized for these basic activities."

"Of course," Koolhaas continued, "I also launched the suggestion that after 25 years you could simply declare buildings redundant because they are so mediocre. Milstein Hall is only about one third of the way to total obsolescence; Rand Hall, being over 100 years old, must therefore be completely worthless."10

Notes

1 "Milstein Hall Cornell University."

2 The fact that limited work was done in Rand Hall as part of the Milstein project had much to do with the anomalous character of Rand Hall compared with other campus buildings: it was built as a type of utilitarian structure at the beginning of the twentieth century to house a machine shop, pattern shop, and electrical laboratory, and was slated to be emptied of the architectural design studios that had camped out there since the mid-1970s once Milstein Hall was completed.

3 ICC, Code and Commentary, 7–93.

4 "Milstein Hall Cornell University."

5 Wolfgang Tschapeller Architekt, "Site narrative," Cornell University Fine Arts Library 100% Schematic Design, Dec. 2, 2014, accessed April 17, 2023, but no longer here as of Feb. 2026; instead, use this link to my personal copy of the same document.

6 Jonathan Ochshorn, "The Cornell Fine Arts Library Site Narrative," Impatient Search (blog), here.

7 "Milstein Hall's Innovative Design."

8 Jonathan Ochshorn, "Koolhaas proposes temporary toilets and fire exits in 'flexible' Milstein Hall as Rand Hall closes for two years," Cornell Chronicle parody, April 30, 2017, here. This parody uses and alters much of the text from: Guy Horton, "What's so Different about Koolhaas's Venice Biennale?" Metropolis (March 27, 2014), accessed April 11, 2023, here.

9 For Bill Millard's recommendation to build ducks in order to avoid value-engineering cost cutting, see Millard, "Banned Words," 91.

10 Koolhaas's comment about buildings becoming obsolete in 25 years is based on a quote from Obrist, "Dynamic Labyrinth (Seoul)," 66.

contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 4 |