contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits |

INTRODUCTION

This is a book about architectural failure. In addition to some general observations and an occasional digression, the heart of the book is a rather detailed examination of dysfunction, inflexibility, fire hazard, nonstructural failure, and unsustainable design in Milstein Hall at Cornell University, the flagship building designed by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) for Cornell's College of Architecture, Art and Planning.

The choice of Milstein Hall is both arbitrary and pragmatic: arbitrary because many other buildings might have served as case studies for the particular problems I enumerate; pragmatic because, as a member of Cornell's faculty since 1988, I have had special access to the building's planning, design, construction, and occupancy.

In fact, I have been thinking and writing about Milstein Hall since 2009, when the college dean sent out an email requesting feedback about the proposed building—whose fate was potentially in limbo at the time due to fallout from the financial crisis of 2008. The dean argued that "it is essential that the faculty weigh in on the project" since "there is apparently an impression that AAP faculty, and the architecture faculty in particular, are divided or even apathetic about the need for the project."1 Well, I did weigh in at that time, and continued to criticize the building plans as they developed, as the building was being constructed, and after the building was occupied.

In spite of my obvious antipathy to the building design, the dean approved my proposal to create a series of Milstein Hall construction videos: my intention was to shadow the contractors, ask lots of questions, and videotape the work in progress with a low-resolution Flip Video camera. It is likely that my proposal was approved because—and here I'm speculating—an "educational" component that was included as part of the contractor's contractual obligations in constructing Milstein Hall elicited no other competing faculty proposals. So I made a series of ten informal videos,2 and learned quite a lot about the building in the process.

I also eventually, and with great effort on my part, got hold of a set of Milstein Hall working drawings. In fact, I wrote a screenplay in two acts, describing the painful ordeal of gaining access from the college, called "Half-Life of a Working Drawing"—a cautionary tale concerning academic freedom compiled verbatim from emails exchanged between 2012 and 2013—but I haven't yet had the courage to make it public. In any event, having access to a working drawing set, especially when combined with my numerous Milstein Hall site visits to document the construction process, proved to be quite valuable in understanding how this building was put together and why it has had so many problems.

Although my questions to Cornell facilities staff about Milstein Hall were, and remain, often unanswered, I was able to obtain additional information about interactions among Cornell's project managers, Milstein Hall's architects and consultants, and City of Ithaca code enforcement officials—based on minutes of meetings and email correspondence—by submitting freedom of information law (FOIL) requests to the City of Ithaca.

Finally, writing and researching my monograph from 2021, Building Bad: How Architectural Utility is Constrained by Politics and Damaged by Expression,3 provided a useful theoretical base for the present work, which is, in effect, a case study in building bad. The competition driving dysfunctional modes of expression and the political/economic calculations that effectively constrain durability and safety—both of which increase the probability of building failure—are theorized in Building Bad. And this theory applies to most avant-garde architecture, including the architecture of Milstein Hall. The present book does not rehash the underlying theoretical arguments for nonstructural failure that appeared in Building Bad; instead, it examines what such failure looks like in a single building—as a case study.

Similarly, there is no attempt in the present book to systematically link each instance of architectural failure in Milstein Hall to the theorizing of Rem Koolhaas and OMA-AMO (AMO being the "research, branding and publication studio of the architectural practice"4). In a few instances, connections between the design of Milstein Hall and the architects' design philosophy are briefly noted: Bill Millard's explanation of inflexibility in the work of OMA is discussed in chapter two. Contradictory attitudes toward large, interconnected spaces and atriums in Milstein Hall—based on Koolhaas's essay on "Junkspace"—are analyzed in chapter six. Finally, Koolhaas's embrace of fiction and false facts in Delirious New York provides some context for the various "fictions" that show up in published commentary on Milstein Hall, enumerated in chapter seven. But all these observations are incidental; this book is not intended as a comprehensive analysis of Koolhaas or his writing. Rather, my hope is that this book helps reorient architectural criticism away from subjective responses to form and expression, and toward more objective analyses of utilitarian functionality in buildings.

There are 26 chapters in the book organized into four parts—with each part corresponding to one category of architectural failure:

- Part I (Dysfunction and Inflexibility) includes detailed discussions of function, flexibility, privacy, lighting, acoustics, circulation, orientation, and access.

- Part II (Nonstructural Failure) offers a theoretical analysis of peculiarity and redundancy as parameters affecting nonstructural failure, as well as an examination of thermal control, rainwater control, and sloppy, dysfunctional, and dangerous details in Milstein Hall.

- Part III (Fire Hazard) discusses the many ways in which Milstein Hall contravenes normative fire safety standards, focusing on its excessive floor area; inadequate or nonexistent fire walls and fire barriers; and unsatisfactory egress from assembly spaces.

- Part IV (Unsustainable Design) is in equal part a critique of Milstein Hall's sustainability and the cynical use of the LEED Reference Guide as validation for Milstein Hall's "green" credentials—structured around LEED's sustainability categories: site, water, energy, materials, indoor environmental quality, and innovation.

Some topics have confounded my effort at systematic organization— discussion of egress, for example, can be found not only in Part III on fire hazard, but also in Part I (e.g., chapter five on circulation) and Part II (e.g., chapter 12 on dangerous details). And certain chapters could well have been moved—thermal control, for example, ends up in Part II (on nonstructural failure) but would have worked just as well in Part IV (on unsustainable design).

As to why someone might be interested in reading such a detailed examination of architectural failure in a single building, the primary reason is this: failure, as Henry Petroski has demonstrated in numerous books and articles on engineered structures, is a necessary prerequisite for success. Designers, clients, and users of architecture, having confronted the errors in this building, may be less inclined to repeat them. A second reason, also quite important, is that language used to explain architecture can be deceptive and dangerous—worse than mere puffery in that it is often taken seriously—so being exposed to such deceptions, even in a single building, might serve as a kind of inoculation against the disease.

***

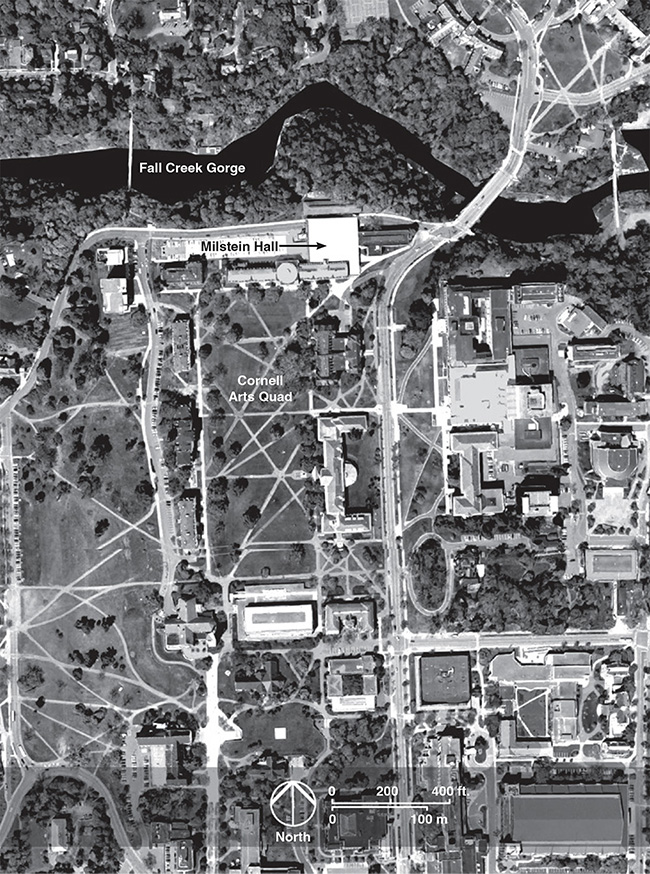

Milstein Hall—on Cornell University's Ithaca, New York, campus—is sited just south of Fall Creek Gorge, the largest of many spectacular tributary streams that feed into Cayuga Lake, as shown in figure 0.1.

Figure 0.1. Topographic map of Ithaca, New York, with Milstein Hall at Cornell University in the center.

A closer look at the Cornell campus, with Milstein Hall visible just north of Cornell's Arts Quad, appears in figure 0.2.

Figure 0.2. Milstein Hall and the Cornell campus.

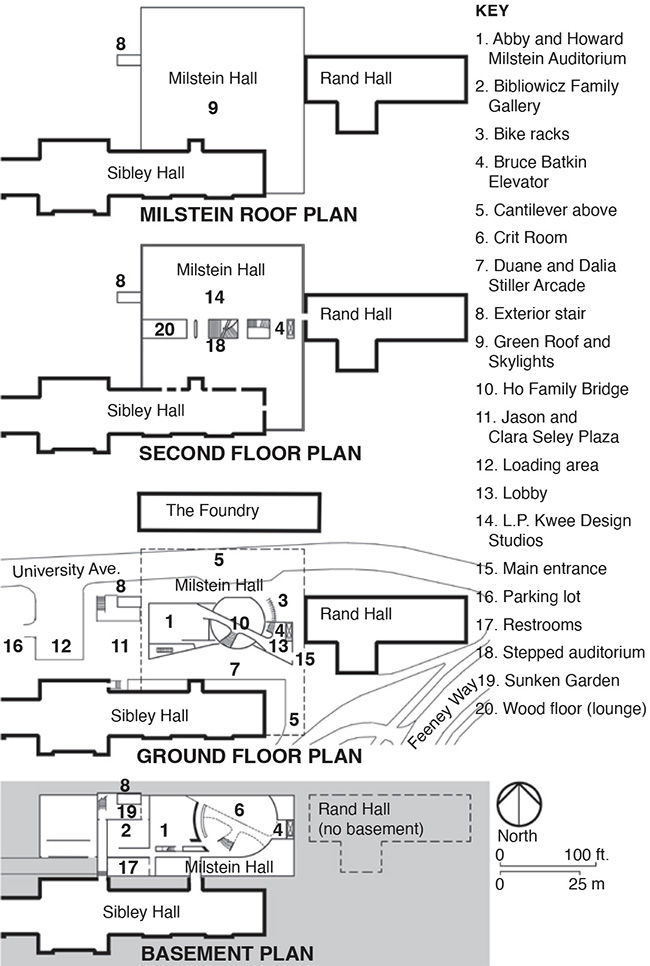

Finally, looking closer still, schematic building plans for Milstein Hall (and adjacent Sibley and Rand Halls) are assembled in figure 0.3 with rooms and spaces inside and outside of the building identified for future reference.

Figure 0.3. Schematic plans for Milstein Hall, in the context of Sibley and Rand Halls.

Notes

1 Email from Kent Kleinman, dean of Cornell's College of Architecture, Art and Planning, to college faculty, Feb. 6, 2009.

2 For links to my Milstein Hall construction videos on YouTube, see Jonathan Ochshorn, "Milstein Hall Construction Videos," here.

3 Ochshorn, Building Bad.

4 "AMO: Company—Rotterdam, Netherlands," Spatial Agency, here.

contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits |