Building Bad: How Architectural Utility is Constrained by Politics and Damaged by Expression

contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 9 |

10. EXPRESSION OF UTILITY

Most of what counts as the expression of utilitas—that is, the expression of those utilitarian functions or activities that a building is intended to support—has developed incrementally, over time, within particular cultures. This happens to the extent that the forms associated with particular activities became familiar and recognizable as such: gas stations look a certain way (like gas stations), and so the form becomes an expression of—a symbol of—"gas station." Elementary schools look a certain way (like elementary schools), and so the form becomes an expression of—a symbol of—"elementary school." Office buildings look a certain way (like office buildings), and so the form becomes an expression of—a symbol of—"office building"; and so on. If this appears tautological, it is because this type of expression is nothing more than the equation of the appearance of a building type with the symbolic expression corresponding to that building type's appearance. This type of self-evident expression permits humans within a given time and place to read (understand) the utilitarian functions assigned to much of the built environment.

To the extent that utility fosters expression through this simple process of association, such expression simply communicates a self-evident purpose or function. A more radical tradition in architectural theory goes further, equating utility with venustas, or fitness with beauty, mostly through an analogy to natural form. The idea is that when something is designed, or evolves to fit its purpose precisely, it then requires no further ornamentation or elaboration: it will be beautiful because it is functional. Joseph Gwilt, to cite but one example of the articulation of this principle, writes in the 1867 edition of his Encyclopedia of Architecture:

Throughout nature beauty seems to follow the adoption of forms suitable to the expression of the end. In the human form, there is no part, considered in respect to the end for which it was formed by the great Creator, that in the eye of the artist, or rather, in this case the better judge, the anatomist, is not admirably calculated for the function it has to discharge; and without the accurate representation of those parts in discharge of their several functions, no artist by means of mere expression, in the ordinary meaning of that word, can hope for celebrity.1

By the early 20th century, this type of form, created in a manner analogous to natural processes, was given the name "organic," as described in 1907 by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in his Essays and Lectures on Shakespeare:

The form is mechanic, when on any given material we impress a predetermined form, not necessarily arising out of the properties of the material; as when to a mass of wet clay we give whatever shape we wish it to retain when hardened. The organic form, on the other hand, is innate; it shapes, as it develops, itself from within, and the fulness of its development is one and the same with the perfection of its outer form. Such as the life is, such is the form.2

Several years later, in 1914, Frank Lloyd Wright adopted the word "organic" to describe his own architecture ("By organic architecture I mean an architecture that develops from within outward in harmony with the conditions of its being as distinguished from one that is applied from without."3), and, 25 years later, in his George Watson Lectures delivered in London, Wright fleshed out the idea that beautiful (organic) form was the "common-sense" outcome of function and materials:

So here I stand before you preaching organic architecture: declaring organic architecture to be the modern ideal and the teaching so much needed if we are to see the whole of life, and to now serve the whole of life, holding no 'traditions' essential to the great TRADITION. Nor cherishing any preconceived form fixing upon us either past super-sense if you prefer, present or future, but—instead—exalting the simple laws of common sense—or of—determining form by way of the nature of materials, the nature of purpose so well understood that a bank will not look like a Greek temple, a university will not look like a cathedral, nor a fire-engine house resemble a French château, or what have you? Form follows Function? Yes, but more important now Form and Function are One.4

The idea that a logical and precise attention to functionality will inevitably lead to beauty can be seen as a middle ground between two extreme positions. At one extreme is the idea of "mechanic" form articulated by Coleridge, implying an independence between utilitarian function and beauty. This idea can be traced all the way back to Vitruvius, who argued that "if we do not gratify [the eye's] desire for pleasure," then the outcome will be "clumsy and awkward." A building's form ought to be tweaked, according to Vitruvius, not to more precisely meet some utilitarian objective, but simply to make it more beautiful, for example, to "counteract the ocular deception [corresponding to the observation of corner columns] by an adjustment of proportions."5

At the other extreme is the "functionalist" view that beauty is not even a relevant criterion for designing buildings. Such a view—that not only is beauty not an inevitable outcome of a logical and utilitarian design process, but that beauty is not even a relevant criterion for architectural design—turns out to be more of a straw man in the history of architectural theory than a serious protagonist. Adrian Forty makes this point, writing that

while some of the views about function expressed by German-speakers in the late 1920s might seem straightforwardly mechanistic—for example Hannes Meyer's often-quoted article 'Building' that begins 'All things in this world are a product of the formula: function [funktion] times economy'—the foregoing discussion makes it clear that … this was by no means a generally held point of view, and was no more than an extremist's polemic within the context of a larger debate about the extended meaning of 'function.'6

Forty criticizes Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson, authors of the influential book, The International Style, arguing that "in order to present modern architecture as a purely stylistic phenomenon, they had to invent a fictitious category of 'functionalist' architecture to which they consigned all work with reformist or communist tendencies. In fact," Forty continues, "their categorization of the 'functionalists' as those to whom 'all aesthetic principles of style are … meaningless and unreal' bore so little relation to what had been happening in Europe that they succeeded in finding only one architect, Hannes Meyer, who fitted their description."7

Yet Meyer, though certainly in the minority, was not entirely wrong about the possibility of designing buildings on the basis of function and economy alone. In fact, buildings are often designed and constructed in this way; the presupposition of "socially necessary" normative form—buildings designed and intended to satisfy merely utilitarian requirements, at least as understood within a given culture—is taken, by analogy, from Marx's concept of "socially necessary labor," allowing us to be precise about varying and unstable social conditions that otherwise would be impossible to pin down.8 Whether or not designers or beholders attribute non-utilitarian qualities to such normative utilitarian buildings does not invalidate the premise; they are simply attaching a "utility equals beauty" disclaimer to the "functionalist" bugbear. This elaboration of Meyer's argument shows up whenever "primitive," "indigenous," "vernacular," or "engineering" works are cited as sources of inspiration, for example, in Bernard Rudofsky's celebration of Architecture Without Architects or in Le Corbusier's invocation of utilitarian grain elevators in Vers une architecture, notwithstanding the fact that Le Corbusier painted over—retouched—the images to remove decorative embellishments: "Each of the borrowed grain elevator pictures was painted with a mixture of pigment, natural gum, and water known as gouache. The gouache allowed Le Corbusier to remove imperfections, reshape buildings, and produce a cleaner, less-granulated photograph than either Gropius or the Atlas Portland Cement Company had been able to achieve."9

Aside from the trivial type of expression that simply becomes associated with utilitarian forms through repeated exposure, it is also possible that building designers intend the buildings' functions or activities to be expressed (symbolized) with more nuance or subtlety, or that beholders attribute to the buildings' functions or activities something symbolically more nuanced or subtle. In that case, we enter into a different, contentious, and subjective territory whose gatekeepers are the critics and connoisseurs seeking to establish new, often arcane, and typically class-based frameworks within which architecture can be analyzed and judged.

One persistent trope is the idea that formal qualities of enclosure systems provide information about, or evidence of, the structural or constructional characteristics of interior spaces. For example, the 19th-century German architectural theorist Karl Bötticher, eager to explain (justify) the mimicking of wooden joists on the surface of Greek temples constructed of stone, proposed a theoretical scheme in which a superficial or decorative "art-form" represents or expresses a necessary and internal "core-form." The art-form, according to Harry Mallgrave, "came to be seen as the artistic dressing applied to the core-form, symbolizing in effect its mechanical or structural function."10

This metaphorical notion of transparency is hardly unique to the 19th century but emerged in the Middle Ages and continued into 20th-century modernism. The historian Erwin Panofsky argues that

as High Scholasticism was governed by the principle of manifestatio, so was High Gothic architecture dominated—as already observed by Suger—by what may be called the 'principle of transparency.' … And so did High Gothic architecture delimit interior volume from exterior space yet insist that it project itself, as it were, through the encompassing structure; so that, for example, the cross section of the nave can be read off from the façade.11

That the spatial logic of interior spaces should be "transparently" revealed (expressed) on a building's exterior surfaces was also a tenet of 20th-century modernism. This can be seen, for example, in the argument made by Alan Chimacoff and Klaus Herdeg in their scathing criticism of I.M. Pei's Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University, published in Cornell's student-run newspaper in 1973 (and, in slightly revised form, in Herdeg's The Decorated Diagram: Harvard Architecture and the Failure of the Bauhaus Legacy, ten years later):

Hypothetically, meaning could exist in two spheres. First, the physical expression of the building's functional organization (the famous shibboleth of Modern Architecture); second, the manifestation of an aesthetic and intellectual argument addressing itself to a range of historical and cultural issues which attach themselves to the project at hand. The Johnson Museum addresses itself to neither. With respect to the first sphere of meaning, it presents schizophrenic inconsistencies, the most blatant of which is the disposition of the gallery spaces themselves. The form of the building would suggest that the 'great north slab' contained spaces of similar and perhaps repetitive use, while the spaces assembled to the south of 'the slab' connote a contrasting, perhaps unique, set of uses. It appears contradictory that the gallery boxes are buried in 'the north slab' and sculpturally expressed within 'the great void.'12

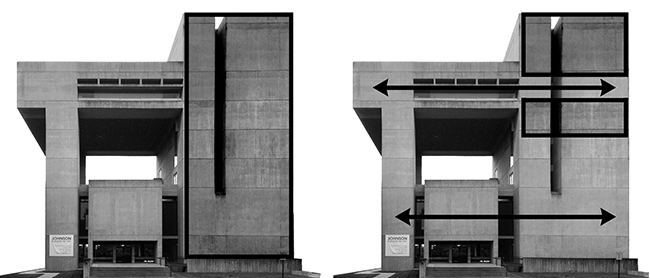

In other words, the museum's great crime was to have been designed from the outside, on the one hand, so that its "great north slab" would, through its massing, align with historic academic buildings on the north side of Cornell's arts quad, and, on the other hand, designed from the inside so that its complex, and somewhat contradictory, programmatic requirements could be met. Since there were not enough administrative spaces to fill the "great north slab"—which would have, per Chimacoff and Herdeg's logic, given it conceptual consistency by reconciling internal programming with external form—and since the form of the "great north slab" was nevertheless desired because its external massing was considered of paramount importance, per the architect's logic, in relation to spatial patterns prevailing on Cornell's historic arts quad, I.M. Pei employed a design strategy which allowed the exterior form to "respond" to exterior conditions while allowing the interior spaces to independently "respond" to programmatic requirements (Fig. 10.1). Of course, it is possible that both criteria could have been met in a manner that reconciled the two imperatives. But, even so, the stipulation for such metaphorical "transparency" is quite arbitrary; one could just as easily praise the museum's design for eschewing such facile expression and, instead, embracing the contradictions of its site and program. In the final analysis, the contentiousness of arguments about the appropriateness—some might say the truthfulness—of such subjective determinations of expression is inversely proportional to the objective basis underlying the claims: nothing elicits more passionate and cut-throat criticism than arbitrary, subjective, and fleeting expressions of taste.

Figure 10.1. Viewed from the exterior, I.M. Pei's Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University is articulated into what Chimacoff and Herdeg call a "great north slab," shown (left) with a black outline that appears to contain "spaces of similar and perhaps repetitive use," in contrast to gallery spaces in the rest of the composition. Understood from the interior (right), it turns out that "gallery boxes are buried in 'the north slab' and sculpturally expressed within 'the great void,' " with only two floors of repetitive office and conference rooms, shown with black outlines, actually within the "great north slab."

In fact, Herdeg was quite willing to make an exception for such "schizophrenic inconsistencies" if he could identify an acceptably ironic attitude at work. For example, in approving Le Corbusier's house at Vaucresson, he admits that

all this posturing on the front facade makes it actually too large and apparently massive compared to the few rooms inside, its outside having little correspondence with what lies behind it in total opposition to the modern movement belief that the exterior of a building should reflect its interior, or that 'the plan should generate the facade,' as Le Corbusier was fond of saying.13

In instances like this, where irony trumps the literal or expressive correspondence between inside and outside, we discover the perfect non-falsifiable refuge of the connoisseur!

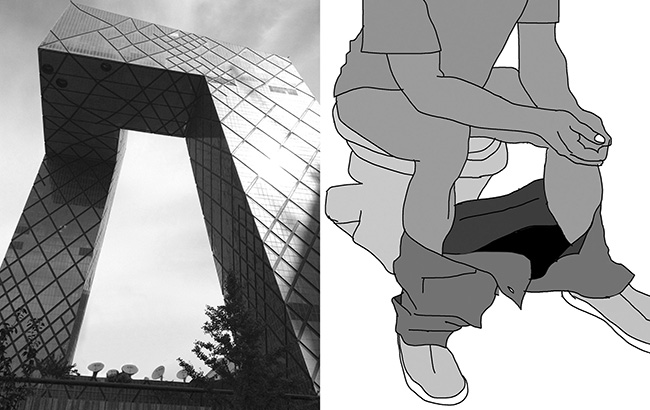

This type of expression is, by definition and design, subjective and obscure. Only critics, connoisseurs, and their initiates can read such designs "properly," although this does not prevent such designs from taking on any number of (unintended) symbolic/expressive values. Consider the CCTV tower in Beijing, designed by Rem Koolhaas, as one example among many. In an interview with Spiegel, Koolhaas argued that the intended expression of the building's function was, naturally, quite nuanced and sophisticated: "Now that it's almost complete, the way it functions becomes clear. It looks different from every angle, no matter where you stand. … That was what we wanted: To create ambiguity and complexity, so as to escape the constraints of the explicit."14 Yet this type of expressive framework is not easily internalized by the uninitiated masses, at least at first: "Mocking monuments, a form of architectural appropriation, is common to the Chinese construction culture, but the most recent invention—referring to CCTV as the 'Big Underpants' Building'—has caused a stir and a laugh on several websites"15 (Fig. 10.2) .

Figure 10.2. The intended expression of Koolhaas's CCTV headquarters in Beijing was nuanced and sophisticated (left), yet the expression of "Big Underpants" prevailed within the popular imagination (right).

Of course, initial popular reception does not necessarily persist over time. Before its unveiling at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, the Eiffel Tower was famously scorned by "forty-seven of France's most famous and powerful artists and intellectuals [who] signed their names to an angry protest letter," calling it a "dizzily ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a black and gigantic factory chimney, crushing [all] beneath its barbarous mass … which even commercial America would not have."16 Yet it has turned into a symbol of "enduring glamour and popularity" and is ubiquitous "as a globalized image" of Paris and France.17 The point is not that OMA's CCTV building, by analogy to Eiffel's Tower, will also come to be embraced as a glamorous symbol of Chinese modernity; rather, the point is that symbolic expression—except for the trivial case of conventional building form symbolically representing functions that have come to be associated with such forms—is neither determined by the designer of the form nor intrinsically related to the form itself.

While this might seem non-controversial, there are still theorists and social scientists who are eager to prove the opposite: that, in fact, certain forms are inherently expressive or symbolic to all humans, irrespective of time, place, or culture. This idea, promoted by Charles Osgood and his collaborators in 1975, was discussed in Chapter 9. Yet even Osgood implicitly admits that, when it comes to artistic expression, it is the cultural framework one inherits that determines the meaning, rather than some innate quality in the work itself. After finding "that artists have highly polarized and emotional reactions to abstract paintings," Osgood turns his attention to ordinary non-artists evaluating the same works and finds that "semantic chaos results. … When non-artists judge a set of abstract paintings, there is very little structuring of the judgments—as if they had no frame of reference for the task."18

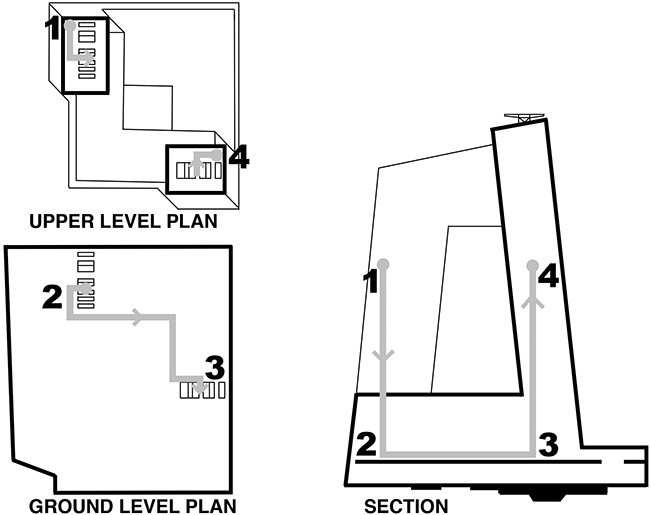

Whatever frame of reference underlies the evaluation of a painting's artistic expression, no threat is posed to the painting itself or the functionality of the physical space it occupies. The painting remains safely confined within its literal frame. Yet the expression of architectural utility is hardly confined in the same way and, in some cases, such expression may actually compromise the building's functionality. An example can be seen in the "looped" circulation system within Koolhaas's CCTV Tower in Beijing. From a purely utilitarian standpoint, circulation systems are needed to facilitate interrelationships among activities associated with various internal rooms and spaces, whether at a residential scale (hallways connecting bedrooms, bathrooms, kitchen, living areas) or at a commercial/institutional scale (corridors connecting offices, meeting rooms, elevators, egress stairs; or vestibules, lobbies, and waiting rooms providing transitional spaces in service of other rooms or areas). In some cases, they can be so complex that movement and orientation require a comprehensive system of signs. A building like Grand Central Terminal in New York City, for example, could not function without utilitarian signs pointing users to subways, food courts, trains, restrooms, ticket counters, and so on (Fig. 10.3). Such "signed" circulation systems function adequately to the extent that movement between any two given points is not needlessly constrained. To get from the upper to the lower level, one just goes down one level, rather than being forced to first go up one level and then down two levels.

Figure 10.3. Without signs literally painted on the stone arches at Grand Central Terminal in New York City, orientation and circulation would become impossible.

Yet Koolhaas argues that precisely such dysfunctional circulation—going up in order to go down, or vice versa—is a feature rather than a flaw in the CCTV Building: "The interesting thing to us is that all these entities at CCTV [referring to production, scriptwriting, business, etc.] are in one single structure and that they can be organized in a loop, so that every part is connected to another."19 First, it is not clear why a "loop" is beneficial in connecting the various parts of the CCTV organization. In his humorous series of "patent" drawings, the intention of CCTV's circulation system is said to avoid "the isolation of the traditional high-rise by turning four segments into a loop," because "a loop of building can be generated that unites and confronts its population in a single whole and cements a coherence of elements, isolating and separating them."20

Aside from the incoherence of this explanation (how is "isolating and separating them" consistent with "a single whole [that] cements a coherence of elements"?), it can be easily shown that this loop is relatively dysfunctional, and not only because it requires duplication of vertical circulation systems (elevators and egress stairs). This duplication is necessary since there are, in fact, two disconnected floor plates at most levels. Yet in spite of this duplication, it is still quite difficult for people in different offices to find each other. To get from floor 30 in Tower 1 to floor 30 in Tower 2, one must go down from the 30th floor of Tower 1 to the lobby level, walk across from the Tower 1 to the Tower 2 elevator banks, and take another elevator up to the 30th floor of Tower 2 (Fig. 10.4). This is no different from organizing the CCTV offices in two separate towers, connected only at the ground level, and much less efficient than organizing the entire program in a single tower.

Figure 10.4. To get from point 1 to point 4, two offices on the same level in OMA's CCTV Tower in Beijing, it is necessary to first go to the lobby level (point 2), walk across to the elevator bank for the other tower (point 3) and then take another elevator up to point 4.

Remarkably, Koolhaas thinks that this expression of circulation is a logical outgrowth of a functional analysis—a "serious effort"—and resents any comparison of his looped tower with buildings, such as Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, that he characterizes as mere "architectural spectacles."21 In fact, this insistence that the spectacular architecture routinely created by his office is somehow different from—more serious than—that produced by his peers is a current that runs through much of his commentary: Peter Eisenman is similarly dismissed as someone whose "subversive" work is really just "another fiction or fairytale," that is, "a style and nothing more."22

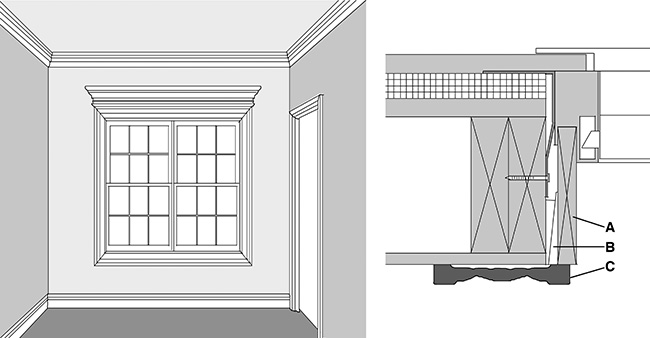

The expression of utilitarian function has one more variation, in which utility is expressed with such exuberance that its underlying functionality is obscured. Under this category are things like trim and molding, whose utilitarian function is simply to mediate between two surfaces that are, on their own, incapable of being easily, or cleanly, joined together. This often occurs, for example, when doors or windows are inserted into so-called rough openings, leaving a space for leveling and shimming that must be covered up somehow (Fig. 10.5). It also often occurs at the intersection of perpendicular surfaces like walls and ceilings or walls and floors, where baseboard or ceiling molding is sometimes employed to finesse what otherwise might be an awkward intersection. The awkwardness comes about for different reasons: sometimes two surfaces are difficult to join together because they need room to expand and contract; sometimes because their surface textures (rough vs. smooth) are not compatible; or sometimes because the tolerances commonly accepted in construction leave gaps between them. Sometimes baseboards are desired, irrespective of these compatibility issues, simply to protect wall surfaces from floor cleaning protocols involving brushes, brooms, vacuum cleaners, and mops that might otherwise damage an unprotected wall surface. Over time, such utilitarian "sliding joints" have evolved into formal devices that are commonly used, or sometimes eschewed, on the basis of their stylistic or aesthetic meaning, irrespective of their underlying utility.

Figure 10.5. The expressive quality of moulding and trim evolved from the utilitarian need to cover shimmed spaces or awkward intersections of perpendicular surfaces. This can be seen in the perspective sketch showing window and door trim, as well as baseboard and ceiling mouldings (left). The detail of an ordinary window (right) shows the window's jamb extension (A), the open, shimmed space between the finished window frame and the rough opening behind it (B), and the moulding or trim (C) whose underlying utilitarian function is to cover the otherwise open, shimmed space.

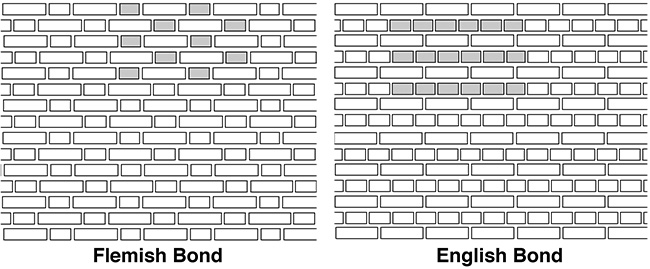

Another example of the elaboration of utilitarian functions into expressive systems occurs in traditional loadbearing brick walls, where multiple layers (wythes) of brick must be physically tied together, or bonded, so that the multi-wythe walls behave structurally as single, monolithic units (strong) rather than as multiple independent and disconnected units (weak). To tie a multi-wythe wall together, some bricks are turned perpendicular to the wall surface, so that they span between two wythes and in that way bond the wythes together. These perpendicular "header" bricks may well form a repeating pattern, and various nations have lent their names to the distinctive designs that have evolved as expressive bonding strategies within their own brick-laying cultures (Fig. 10.6). Needless to say, one can also find such patterns employed in contemporary single-wythe brick cladding, where the traditional bonding function from which these patterns emerged no longer exists.

Figure 10.6. The utilitarian function of bonding multiple layers (wythes) of a loadbearing brick wall using header bricks—shown shaded—has evolved into an expressive function with variations corresponding to different national brick-laying cultures.

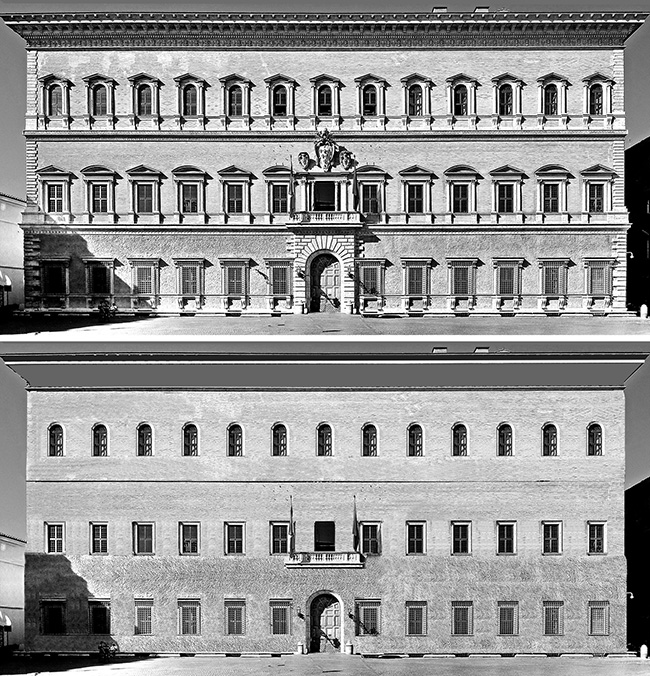

These examples, in which utilitarian functional elements have evolved into an independent expressive system, thus serve as a transition to the entirely gratuitous use of superimposed symbols in what Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour call decorated sheds.23 Both in the ordinary house shown in Figure 10.7 and in the Palazzo Farnese in Rome—a canonical example of the "decorated shed" provided by Venturi et al. and shown in Figure 10.8—various exterior elements have become literally detached from functional necessity and are applied to the surface of the facade as pure symbolic expression. In both the modest and monumental versions, the principle is the same.

Figure 10.7. The top image shows a house on which both exterior trim and roof elements have been applied to the exterior surface as elements of symbolic expression; the bottom image shows the same house—identical in form and utilitarian function—but with all gratuitous elements digitally removed.

Figure 10.8. The top image shows the Palazzo Farnese, a High Renaissance palace in Rome designed by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger beginning in 1515 (with Michelangelo redesigning the third story and cornice later in the sixteenth century); the bottom image shows the same facade, digitally stripped of its decorative elements.

Expressing utility in the manner illustrated in these examples was anathema to most of the heroic modernists at the beginning of the 20th century, since elaboration of moldings and decorative treatment of brick bonding were inconsistent with the ethos of geometric abstraction that formed the basis of their architecture. This ideological aversion to building elements like trim or copings—elements that were understood as traditional building elements rather than being subsumed within abstract systems of surface and void—is one of several factors that have led to a virtual epidemic of non-structural building failure. This phenomenon is further discussed in the following chapters.

Notes

1 Gwilt, Encyclopedia of Architecture, 796, quoted in De Zurko, Origins of Functionalist Theory, 122.

2 Coleridge, Essays and Lectures on Shakespeare, 46–47, quoted in De Zurko, Origins of Functionalist Theory, 118.

3 Wright, "In the Cause of Architecture, Second Paper," 406 (see footnote).

4 Wright, An Organic Architecture, 4.

5 Vitruvius, The Ten Books on Architecture, 84.

6 Forty, "Function," in Words and Buildings, 185, 187.

7 Forty, "Function," in Words and Buildings, 187 (ellipsis in Forty's excerpt, not in the original text).

8 Marx, "Results of the Immediate Process," 1019.

9 Tell, "The Rise and Fall of a Mechanical Rhetoric," 163–64.

10 Mallgrave, Gottfried Semper, 220.

11 Panofsky, Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism, 43–44.

12 Alan Chimacoff and Klaus Herdeg, "Two Cornell Professors: 'A Promise Unfulfilled,'" The Cornell Daily Sun, May 4, 1973. The same article, slightly revised, appears ten years later in Herdeg, The Decorated Diagram.

13 Herdeg, The Decorated Diagram, 18.

14 Stephan Burgdorff and Bernhard Zand (interviewers), "An Obsessive Compulsion towards the Spectacular," Spiegel International, July 18, 2008 (my italics), here.

15 Movingmaster, "Mocking the Monument: CCTV snapshots," MovingCities.org, December 10, 2008, here.

16 Jonnes, Eiffel's Tower, 26–27.

17 Jonnes, Eiffel's Tower, 311.

18 Osgood, Suci, and Tannenbaum, The Measurement of Meaning, 293.

19 Koolhaas and Obrist, "China Interview," in Rem Koolhaas, The Conversation Series, 6.

20 Koolhaas, "Universal Modernization Patent," 511.

21 Koolhaas and Obrist, "China Interview," in Rem Koolhaas, The Conversation Series, 6.

22 Koolhaas and Obrist, "Between-Cities Interview," in Rem Koolhaas, The Conversation Series, 51–52.

23 Venturi, Scott-Brown, and Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas, 64.

contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 9 |