Building Bad: How Architectural Utility is Constrained by Politics and Damaged by Expression

contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 8 |

9. INTRODUCTORY CONCEPTS

There is a tension between the art and science of architecture originating in the suspicion that focusing too intently on practical and utilitarian considerations could overwhelm the conceptual and abstract fantasies that increasingly characterize architectural style.1 The Roman architect, Vitruvius, would not have understood the basis for such a fear, as he considered the formal or abstract qualities of architecture (manifested in venustas, or beauty) to be a complementary function of architecture, along with utilitas and firmitas (utility and strength). From his standpoint, there was no conflict between the expressive and utilitarian functions—the art and science—of architecture. So why is there one now? The short answer is that architects, and their clients, are driven by competition to exploit the inexhaustibly mutable expressive potential of buildings. Modernist abstraction, discussed in Chapter 11, has become increasingly disengaged not just from conventional elements of construction, for example, columns, walls, windows, roofs, and so on, but more importantly from an appreciation of structural and control layer theories, to the extent that these building science principles may appear to threaten the hegemony of unfettered architectural expression.

It is this implicit threat that drives a wedge between the rigors of building technology and the freedom of design, affecting not only speculative or "theoretical" unbuilt projects, but also the production of real buildings. At the extreme, the result—for both architecture students and practitioners who have internalized a design method almost completely disengaged from conventional building science principles (aka "reality")—may be a palpable antipathy toward the disciplines of structure, control layer theory, and even the rudiments of what might be called sustainable design.

To dig deeper into this conundrum, one must examine the nature of venustas, the most subjective and contentious element within Vitruvius's functional triad. The first thing one uncovers is the difficulty in pinning down its relation to functionality. This is because the word "function" is used in two ways. First, function is used to identify purely utilitarian qualities. For example, the function of a chair, in this sense, would be to provide a structurally and ergonomically adequate surface for sitting. Second, function is used in a broader sense, to include not only utilitarian aspects, but also subjective and expressive qualities. For example, the chair might also function as an article of conspicuous consumption, or as a means of aligning its owner with a particular stylistic tendency, and so on. Denise Scott Brown has fashioned a similar argument using a table, rather than a chair: "It seems that the functions of so simple and general an object as a table may be many and various, related at one end to the most prosaic of activities and at the other to the unmeasurable, symbolic and religious needs of man."2

Difficulties and confusion emerge when these two meanings of function are not made clear. For example, if "functional" architecture is defined as something, per Hermann Muthesius, without "superficial forms of decoration, a design strictly following the purpose that the work should serve,"3 one can always argue that precisely those things excluded—decoration, ornament, or any other "superficial" elements or strategies—are also part of "the purpose that the work should serve." But this apparent paradox is just an artifact of the alternative meanings of function, nothing more. One must be careful when arguing that the utilitarian meaning of function excludes both gratuitous and symbolic elements. More precisely—since one can neither exclude "symbolism" nor, in general, prescribe what subjective responses will arise in the presence of a work of architecture—this first, utilitarian, meaning of functionality excludes only those elements considered "decorative" or gratuitous and therefore non-utilitarian.

A decorative element embedded in an architectural facade really is an element of the building—it is actually present, can be seen, and consists of tangible material like brick or stone or paint—whereas a so-called symbolic element is little more than a theoretical sleight-of-hand in which a subjective interpretation of a building is given a tangible basis, as if it is actually present (as an "element") in the materials of the building itself. We tend to say: "This food is delicious," as if being delicious is an absolute quality of the food, rather than saying: "I find this food delicious," thereby acknowledging the subjectivity of taste.

Physical or formal aspects of a building may well trigger various subjective responses in individual beholders. And just as a chef cannot create a dish that is objectively delicious, it is the beholders of architecture, rather than the building's designers, who "construct" its meaning. This does not preclude a special role for critics and connoisseurs, but, on the other hand, neither does it give their (often contradictory) opinions an objective status. And designers, working within a subculture in which particular formal strategies are recognized and valued, may well provide precisely the types of coded forms of expression that are recognized as such within those architectural subcultures. However, even in such cases, the formal codes to which they subscribe are external to the forms themselves and must be internalized by the beholder if the intended expression is to be "properly" understood. Those without knowledge of, or interest in, such codes will interpret the same forms through a different lens.

That symbolic expression cannot be found in the physical materials of art or architecture does not mean that such expression does not exist and has no function within artistic production. It is possible to admit some common understandings of symbolic expression within subcultures or even entire cultures, always, however, with the disclaimer that such subjective interpretations can be fractured, revised, or otherwise transformed by individuals or by entire groups. Tracing such movements of subjective phenomena is at best a speculative task, and probably hopeless, given the idiosyncratic psychological content that directs any individual perception towards some subjective interpretation. The Rorschach test, to cite but one example, exploits precisely this indeterminacy in attempting to draw psychological conclusions from the multiplicity of subjective interpretations that can be made from the same formal design.

Commentators on fashion and taste also challenge the idea that it is possible to "design" symbolic content. Joshua Rothman, discussing the "vision" of J. Crew, suggests that the meaning of certain clothing items during "the Obama years" changed when Donald Trump became president: "During the Obama years, nostalgia might have seemed harmless, even admirable, but today it feels like a troubled and doubtful impulse. Does it make sense for young, urban men to dress up like Rust Belt factory workers, or for women to embrace the style of Hyannis Port in the nineteen-sixties? The answers to those questions have changed over the past six months."4 One year later, analysts concerned with the symbolic content of fashion had an even more explicit conundrum: what meaning to attribute to the "I Really Don't Care" jacket worn by Melania Trump, the First Lady, on her way to a children's shelter in Texas. Was it "insensitive," "heartless," and "unthinking"; or was it just a jacket with "no hidden message"? The divergent theories that emerged in the aftermath of "Jacket-gate" reinforce the notion that it is the "beholders" that assign meaning to an object, even one—in this case—where the apparent meaning is literally written on the back of the jacket. Clearly, then, the artists themselves (or the clients who display the "artwork") also have no magic power to embed meaning in the object. Even when an intention may be present in the artist's (or client's) mind, there is no way to guarantee that the intended meaning will be properly understood. In the case of Ms. Trump, "between intention and analysis an enormous gulf can exist" and whatever she may have been thinking, "this time it may have backfired."5 Even the meaning of a plain white coat—the type often worn by doctors and other health care workers—is subject to evolving and diverging symbolic interpretations. While some doctors continue to think of the white coat in positive terms "as a defining symbol of the profession," others—influenced by studies showing that these garments "are frequently contaminated with strains of harmful and sometimes drug-resistant bacteria associated with hospital-acquired infections"—find the meaning far more ominous.6

There is, nevertheless, a tendency to think of aesthetic objects (buildings, paintings, songs, etc.) either as potentially expressive, solely on the basis of their form, or as communicative devices, analogous to language. In the first case, we could cite the mythology propounded by architects like Le Corbusier that Platonic solids are intrinsically beautiful. In the second case, Charles Osgood and his co-authors make the "communication" argument explicitly in their seminal book from 1957, The Measurement of Meaning:

Like ordinary linguistic messages, the aesthetic product is a Janus-faced affair; it has the dual character of being at once the result of responses encoded by one participant in the communicative act (the creator) and the stimulus to be decoded by the other participants (the appreciators). Aesthetic products differ, perhaps, from linguistic messages by being more continuously than discretely coded (e.g., colors and forms in a painting can be varied continuously whereas the phonemes that discriminate among word-forms vary by all-or-nothing quanta called distinctive features). They also differ, perhaps, in being associated more with connotative, emotional responses in sources and receivers than with denotative reactions. … But nevertheless, to the extent that the creators of aesthetic products are able to influence the meanings and emotions experienced by their audiences by manipulations in the media of their talent, we are dealing with communications.7

Yet this notion that a work of architecture—or any aesthetic object—can have a particular meaning embedded in it—meaning which, by analogy to language, is both intended by the architect and able to be decoded by the beholder (or "appreciator," using Osgood's term)—is flawed. Mark Gelernter traces the origin of the idea that material objects do not actually contain "secondary" qualities of beauty or expression to Galileo (1564–1642) who wrote that "tastes, odors, colors and so forth are no more than mere names … and that they have their habitation only in the sensorium." John Locke (1632–1704) borrowed Galileo's distinction between such primary and secondary (subjective) qualities; and the Scottish philosophers Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746) and David Hume (1711–1776) continued this line of reasoning, the former concluding that "were there no mind with a sense of beauty to contemplate objects, I see not how they could be called beautiful," and the latter writing that "it is almost impossible not to feel a predilection for that which suits our particular turn and disposition. Such preferences are innocent and unavoidable, and can never reasonably be the object of dispute, because there is no standard by which they can be decided."8

Even the premise that artists have "intentions"—that they "know" what they intend to communicate—and that decoded responses of beholders are somehow reliable cannot be substantiated. Unlike the denotative function of language where, for example, the sentence "That is a cat" has no likely ambiguity in its intention (as a description) or in its decoding by a beholder, architecture has no denotative function, except in the trivial sense that gas stations, elementary schools, office buildings, and so on communicate their utilitarian functions through their form (see Chapter 10). Architecture as an expressive art, however, is analogous to the connotative use of language, which proves, not that architecture communicates like language, but rather that language can also be employed aesthetically, like architecture.

But in this latter case, neither language nor architecture is being created with explicit and objective intentions and neither language nor architecture can be decoded with any sense of objective certainty. This is because it is impossible to ascertain the motivations of architects that inform their creative process, and it is equally impossible to validate the process of decoding through which beholders assign meaning to works of architecture. Without being certain about the architect's and beholder's motivation in creating particular expressive forms or assigning meaning to a work of architecture, the whole project of intentionality crashes to the ground. According to Erich Fromm:

Courageous behavior may be motivated by ambition so that a person will risk his life in certain situations in order to satisfy his craving for being admired; it may be motivated by suicidal impulses which drive a person to seek danger because, consciously or unconsciously, he does not value his life and wants to destroy himself; it may be motivated by a sheer lack of imagination so that a person acts courageously because he is not aware of the danger awaiting him; finally, it may be determined by genuine devotion to the idea or aim for which a person acts, a motivation which is conventionally assumed to be the basis of courage. Superficially the behavior in all these instances is the same in spite of the different motivations.9

Just as it is hardly clear whether courageous people are aware of their own (true) motivations, or whether beholders of courageous acts can properly decode the true intentions underlying such acts, it is similarly unwise to draw any conclusions about the intention—the meaning—underlying works of architecture. Nor is it necessary to invoke an "unconscious" source for this uncertainty as does Fromm, following Freud. The false consciousness of both architects (with respect to their creative processes) and beholders of architecture (with respect to their conclusions about architecture's meaning) is sufficient to explain both intentions and judgments about architectural meaning without recourse to unconscious motives: "When people put their definitely free will into practice on the basis of false consciousness, they are doing nothing other than making their individuality obedient to the dictates of capital and state in any number of different ways."10 It is within this larger context that the underlying meaning of architecture—building made fashionable for competition—will be discussed in Chapter 15.

E.H. Gombrich refers to a "function of art" in explaining the radical transformation within Greek art between the 6th and 4th centuries B.C.: "Surely," he writes, "only a change in the whole function of art can explain such a revolution."11 That such artistic functionality carries over to works of architecture is a commonplace in architectural writing, although confusion in the use of the term "function" is equally common. For example, Christian Norberg-Schulz, in discussing three functions (he calls them "purposes") of architecture, lists "the functional-practical, the milieu-creating and the symbolizing aspects"—in other words, he considers being "functional" as but one of three functions of architecture. The two other functions of architecture are, in this formulation, not "functional."12

Other writers on architecture insist that being "functional" is not even architecture's primary function. Sigfried Giedion, according to Karsten Harries, "reaffirmed what he took to be the main task [i.e., the main function] facing contemporary architecture, 'the interpretation of a way of life valid for our period.'"13 Along these same lines, Harries proposes to extend to architecture Paul Valéry's claim that the function of poetry is "to create an artificial and ideal order of a material of vulgar origin." Harries writes that the theorists Tzonis and Lafaivre "proclaim that 'the poetic identity of a building depends not on its stability, or its function, or on the efficiency of the means of its production, but on the way in which all the above have been limited, bent, and subordinated by purely formal requirements.'"14 In other words, according to Tzonis and Lafaivre, the function of a building (to create a "poetic identity") comes about by subordinating its utilitarian function to formal concerns.

Aside from assigning architecture the non-utilitarian function of expressing the idealized zeitgeist of the period or, perhaps, the tortured soul (poetic identity) of the individual artist, the early 20th-century concept of "defamiliarization" is also often invoked; here, the function of architectural expression is to "make strange" what otherwise might be taken for granted and therefore not really noticed. At the extreme, we enter into territory typically broached by charlatans, comedians, or logicians who gleefully relate linguistic paradoxes such as that of the Cretan who claims that all Cretans are liars (and so must be telling the truth). In the realm of architecture, the analogous condition is a building with the anti-heroic function of being dysfunctional. Alison and Peter Smithson, for example, proposed in 1957 that "the word 'functional' must now include so-called irrational and symbolic values."15 This sentiment gets echoed and even amplified by some contemporary architects and engineers: Rem Koolhaas writes that the work of engineer Cecil Balmond expresses "doubt, arbitrariness, mystery and even mysticism."16 A more conventional spin on the function of defamiliarization is attributed to the architect Le Corbusier, who is said to have "defined architecture as having to do with a window which is either too large or too small, but never the right size. Once it was the right size it was no longer functioning."17

This idea of defamiliarization would have been anathema to 19th-century theorists like John Ruskin, or his contemporary Edward Lacy Garbett; the latter would have seen only ugliness in buildings with such "immoral" qualities: "I cannot but regard the perfection of domestic architecture as an embodied courtesy," wrote Garbett in 1850. "And will any one dare to say that this courtesy is useless?"18 Well, yes: many architects—and not only in and after the 20th century—celebrated precisely this lack of courtesy, although their stance was contested. A classic confrontation over this issue occurred in a 1982 debate between Peter Eisenman and Christopher Alexander. In the following excerpt, the two architect-theorists discuss the Town Hall at Logroņo (Fig. 9.1) designed by Rafael Moneo in 1973–1974:

Figure 9.1. Rafael Moneo's Town Hall at Logroño.

CA: The thing that strikes me about your friend's building—if I understood you correctly—is that somehow in some intentional way it is not harmonious. That is, Moneo intentionally wants to produce an effect of disharmony. Maybe even of incongruity.

PE: That is correct.

CA: I find that incomprehensible. I find it very irresponsible. I find it nutty. I feel sorry for the man. I also feel incredibly angry because he is fucking up the world. … Don't you think there is enough anxiety at present? Do you really think we need to manufacture more anxiety in the form of buildings?

PE: … What I'm suggesting is that if we make people so comfortable in these nice little structures of yours, that we might lull them into thinking that everything's all right, Jack, which it isn't. And so the role [function] of art or architecture might be just to remind people that everything wasn't all right.19

Alexander, representing the forces of politeness and comfort, asks Eisenman: "Don't you think there is enough anxiety at present? Do you really think we need to manufacture more anxiety in the form of buildings?" Eisenman's response, justifying the disorienting or upsetting qualities of some avant-garde architecture, is that people are thereby reminded "that everything wasn't all right." A similar argument is made by Herbert Marcuse, the German-American philosopher and political theorist, who writes that

a work of art can be called revolutionary if, by virtue of the aesthetic transformation, it represents, in the exemplary fate of individuals, the prevailing unfreedom and the rebelling forces, thus breaking through the mystified (and petrified) social reality, and opening the horizon of change (liberation) … The aesthetic transformation becomes a vehicle of recognition and indictment. But this achievement presupposes a degree of autonomy which withdraws art from the mystifying power of the given and frees it for the expression of its own truth. Inasmuch as man and nature are constituted by an unfree society, their repressed and distorted potentialities can be represented only in an estranging form.20

But it is hardly clear that architecture has the necessary "autonomy" that Marcuse suggests it must have as a revolutionary medium. Unlike the production of literature—the art form that Marcuse is primarily interested in—the appearance of architecture (where appearance is used in the double sense of what it looks like, and its coming into existence) is contingent upon, first, a patron whose interests the architecture serves; and, second, the literal deployment of wealth and power in order to create (bring into existence) the physical elements of architecture. It is true that this first condition could elicit "revolutionary" form, where such formal qualities might serve the patron (client); but that alone cannot overcome the second criterion. It may well be that in literature the revolutionary thing is its printing and distribution as much as the aesthetics of the work itself. The relative ease of printing and distribution, compared to the creation of construction documents and then the actual construction of a building, is, at least in this respect, what separates literature from architecture.

Even if a "disturbing" work of architecture somehow comes into being, its power to "open up the horizon of change (liberation)," being based on the feelings it elicits rather than on conclusions drawn from a logical explanation, puts it immediately into competition with other emotion-based content supplied in much greater quantities by the ideologically driven representatives and apologists of wealth and power. Neil Leach describes how Walter Benjamin, for example, "explored the problem of how Fascism used aesthetics to celebrate war" and how "it could be extrapolated from Benjamin's argument that aesthetics," rather than opening up revolutionary horizons, "brings about an anaesthetization of the political."21

That symbolic content can and should be expressed by a building's outward form is nevertheless taken as self-evident in much architectural theorizing. Christian Norberg-Schulz, for example, writes: "During the great epochs of the past certain forms had always been reserved for certain tasks. The classical orders were used with caution outside churches and palaces, and the dome, for instance, had a very particular function as a symbol of heaven."22 He goes on to argue that not only did such forms correspond to particular social functions, but that there is a physiological (emotional) basis for assigning particular forms to these functions:

The psychologist Arnheim discusses this problem [i.e., the structural similarity between content and form] in detail and maintains that we have the best reasons to assume that particular arrangements of lines and shapes correspond to particular emotional states. Or rather we should say that particular structures have certain limited possibilities for receiving contents. We do not play a Viennese waltz at a funeral.23

Actually, we may well play up-beat music at funerals, for example, as part of the jazz funeral tradition in New Orleans. In other words, there is no intrinsic correspondence between functional activities and the manner in which they are expressed. Some people fear tight spaces; others open spaces. How could one possibly assign some singular meaning to space given the divergent ways in which the same space is experienced? Norberg-Schulz adds that the perception requires "training and instruction … A common order is called culture. In order that culture may become common, it has to be taught and learned. It therefore depends upon common symbol-systems, or rather, it corresponds to these symbol-systems and their behavioral effects."24 Well, of course, if one is told how to interpret a form, the connections can be memorized and regurgitated. Aside from internalizing the meaning of specific symbols, the mere suggestion of an expressive theory, however arbitrary and subjective, might well affect one's subsequent experience. For example, after reading historian Heinrich Wölfflin's argument that "we judge every object by analogy with our own bodies," and that therefore any "object—even if completely dissimilar to ourselves—will … transform itself immediately into a creature, with head and foot, back and front,"25 it is quite possible to start imagining such zoomorphic qualities in buildings or other objects.

Similarly, certain forms—by virtue of being uniquely congruent with the activities they support and, therefore, express—have a relatively stable and widely shared symbolic content. And it is also true that, within a given time and place, the expression of poverty, wealth, and other more subtle distinguishing marks of a class society may well be manifested by formal means. Cole Roskam, for example, makes the case that the characteristic constructional elements of traditional Chinese buildings "over time … took on greater representational significance. Clear hierarchical rankings of buildings determined the particular proportions used, which in turn informed column height, beam span, and the number of bracket sets."26

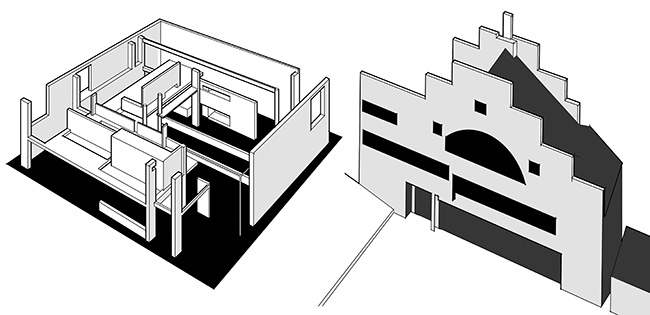

But this is an inadequate model for understanding contemporary societies, which are characterized by multiple and shifting subcultures. What, for example, would constitute the "common symbol-systems" of Peter Eisenman's House I and Venturi and Rauch's D'Agostino House (Fig. 9.2), both projects conceived in 1968? Any answer, in my view, must distinguish between formal modes of expression ("symbol-systems"), which are evidently quite diverse, and the overarching function of such expression, which—consistent with the competition that drives the multiplicity of formal outcomes—always serves to reinforce and validate the various ideologies associated with capitalist freedom: on one side of the coin, democracy and community; on the other side, wealth and power (more on this in Chapter 14). Yet the expression of freedom, triggered by the functional necessity to serve as a mode of competition, may well result in dysfunctional buildings (as argued in Chapter 15) .

Figure 9.2. Peter Eisenman's House I (left) and Venturi and Rauch's D'Agostino House (right), both projects conceived in 1968, provide some evidence that no single zeitgeist can be identified within contemporary societies.

In that sense, and in spite of differences in their formal attributes, the architecture of Eisenman and Venturi (and everyone else) has the same overarching cultural function. It is precisely in supporting that function that the task of reconciling the increasingly deviant manifestations of venustas with building science principles (utilitas and firmitas) grinds to a halt. Having reached this impasse, the struggle with reality experienced by both students and practitioners of architecture—struggling to become accomplices within this maladaptive mode of production—will not soon be assuaged.

Notes

1 A version of this chapter was previously published as Ochshorn, "Utility's Evil Twin."

2 Scott Brown, "The Function of a Table," 154.

3 "Function," in Forty, Words and Buildings, 181.

4 Joshua Rothman, "Why J. Crew's Vision of Preppy America Failed," New Yorker, May 3, 2017, here.

5 Vanessa Friedman, "Melania Trump, Agent of Coat Chaos," New York Times, June 21, 2018, here.

6 Austin Frakt, "Why Your Doctor's White Coat Can Be a Threat to Your Health," New York Times, April 29, 2019, here.

7 Osgood, Suci, and Tannenbaum, The Measurement of Meaning, 290.

8 Gelernter, Sources of Architectural Form, 118, 130–31, 147, 149.

9 Fromm, Man for Himself, 55.

10 "Psychology: Introduction," in GegenStandpunkt, Psychology of the Private Individual.

11 Gombrich, Art and Illusion, 127.

12 Norberg-Schulz, Intentions in Architecture, 22.

13 Giedion is quoted in Harries, The Ethical Function of Architecture, 2.

14 Harries, The Ethical Function of Architecture, 24.

15 "Function," in Forty, Words and Buildings, 187.

16 Koolhaas, "Preface," in Balmond, Informal.

17 Steil et al., "Contrasting Concepts." I cannot validate this attribution with a citation to the original quote by Le Corbusier, although there are numerous secondary references, all saying essentially the same thing, and probably each assuming that their own unattributed source was accurate. This one is from Peter Eisenman.

18 Garbett, Rudimentary Treatise, 9. Quoted in De Zurko, Origins of Functionalist Theory, 140–41.

19 Steil et al., "Contrasting Concepts."

20 Marcuse, The Aesthetic Dimension, xi, 9 (my italics).

21 Leach, "Architecture or Revolution," 114.

22 Norberg-Schulz, Intentions in Architecture, 17.

23 Norberg-Schulz, Intentions in Architecture, 71.

24 Norberg-Schulz, Intentions in Architecture, 72, 79.

25 Wölfflin, Renaissance and Baroque, 77. Quoted in Vidler, The Architectural Uncanny, 72.

26 Roskam, Improvised City, 13.

contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 8 |