Jonathan Ochshorn

© 2010 Jonathan Ochshorn.

Following is my summary and critique of the Green Building Design & Construction Reference Guide, 2009 Edition. Commentary on the Reference Guide can be found in these red boxes, sometimes within each of the chapter links immediately above, but mostly in my summary and critique of the prior version: Version 2.2 NC.

Intent: Like the title says -- minimum IAQ.

Requirements: Two cases: (1) For mechanically ventilated spaces, satisfy ASHRAE Standard 62.1-2007 (with errata but not addenda) sections 4-7, using the "ventilation rate procedure" or any local code if more stringent. Note that ventilation rate procedure is prescriptive ASHRAE option (with IAQ procedure being more performance-based) based on minimum ventilation rates for various types of occupancies. (2) For naturally ventilated spaces, same standard, but only satisfy section 5.1 (with errata but not addenda): this includes the standard historic building code boilerplate requiring openable (vent) area equal to 4% of the net occupiable floor area. Also, such space must be within 25 ft. of openings to the outdoors.

1. Benefits/issues. Same as overview. Emphasizes the need to introduce outside air, per ventilation rate procedure. Raises issue of additional energy costs ("higher energy use"), presumably compared with the option of using less energy by harming the occupants. Most jurisdictions are governed by these ASHRAE provisions in any case.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. ASHRAE Standard 62.1-2007.

4. Implementation: Use some combination of mechanical and/or natural ventilation.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations. Refer to the ASHRAE Standard.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: active = mechanical ventilation; air-conditioning treats air to control temperature, humidity, cleanliness; breathing zone is above 3 ft., lower than 6 ft., and away from walls or HVAC registers; contaminants; IAQ is relative (defined as air that does not exceed legal contaminant concentrations and that does not bother 80% of the occupants); natural ventilation; off-gassing = emission of VOCs (volatile organic compounds) from material; outdoor air; thermal comfort; ventilation.

Intent: Reduce impact of ETS directly on occupants, but also on ventilation air and indoor surfaces.

Requirements: Two cases, the first for all buildings, and the second for residential/hospitality occupancies only. For Case 1, there are two options. Either: (1) No smoking in the building or within 25 ft. of openings/air intakes with signage designating outdoor areas either for smoking or no smoking; or (2) Designated smoking areas within the building, with same outdoor area stipulations. Need to exhaust smoking air directly outside, and maintain negative pressure in such zones. [This seems to allow for the entire building, or a substantial portion, to be designated as a smoking zone.] For Case 2 (residential/hospitality only): No smoking in "common areas." Weatherstrip doors and windows. Seal walls/floors between units. Reiterates outdoor stipulations from Case 1 (seems redundant since Case 1 applies to all buildings).

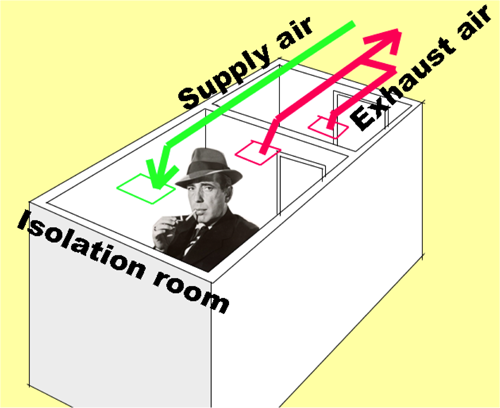

Bogart is isolated in LEED-compliant smoking room.

1. Benefits/issues. Reduces negative impacts of second-hand smoke (ETS). Also economic issues: more cost for separate areas and energy (ventilation) use; but greater employee productivity and less illness, insurance costs.

[From Version 2.2 critique] This is a bit strange to have in a sustainability guideline, since it is impossible to assess its impact. Nothing prevents the current building owner, or a new owner, from changing a smoking policy. On the other hand, smoking is already prohibited in many buildings by state or local law.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. Need to measure "tightness" of separations for smoking areas, or between residence units: (ANSI)/ASTME-779-03 Standard Test method for Determining Air Leakage Rate by Fan Pressurization; also Residential Manual for Compliance with California's 2001 Energy Efficiency Standards (For Low Rise Residential Buildings), Ch. 4.

4. Implementation: Use some combination of mechanical and/or natural ventilation.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations. Refer to the ASHRAE Standard

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples. Reiterates the type of separation and ventilation required for a smoking area: separate ductwork to exhaust contaminated air; floor to deck partitions; weatherstripped doors to maintain negative pressure differential. See diagram, PDF page 447.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations. Some states/cities already have various smoking regulations in place.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: ETS (Environmental Tobacco Smoke) = second-hand smoke with 4000+ airborne particles, some of which are carcinogens; mechanical ventilation; ventilation.

Intent: Checks that outdoor air component of ventilation is actually what it should be (monitoring).

Requirements: Two cases, the first for mechanically ventilated spaces; the second for naturally ventilated spaces. For Case 1, with mechanical ventilation, put CO2 monitors in breathing zone (3-6 ft. above floor) in spaces with 25 or more occupants per 1000 sq.ft.; and measure outdoor airflow (within 15% of target rate per ASHRAE 62.1-2007) in cases where 20% or more of supply is for non-dense spaces (less than 25 occupants per 1000 sq.ft.). For Case 2, with natural ventilation, put CO2 monitors in breathing zone for all spaces; multiple spaces may be monitored by a single CO2 sensor where airflow is induced through all spaces without human (occupant) intervention.

1. Benefits/issues. High CO2 concentrations indicate poor air quality, i.e., inadequate outdoor air input (with 300 to 500 ppm ambient outdoor levels common).

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. Basic ASHRAE Standard 62.1-2007.

4. Implementation: Fan-tracking or pressure measurements do not take the place of actually measuring outdoor airflow. Airflow monitor must provide visible or audible signal when outdoor air falls below required rate. CO2 sensors also need to send signal when concentration exceeds 1000 ppm (or higher, when in compliance with ASHRAE 62.1-2007 -- see Users Manual Appendix A, especially for "demand control ventilation"). Multiple CO2 monitors better (but more expensive) than a single monitor in the return duct. One can alternatively put CO2 sensors indoors and outdoors, and trigger greater outdoor air when the difference equals or exceeds 530 ppm, or use assumed (conservative) 400 ppm for outdoor value.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: breathing zone; CO2, demand control ventilation refers to a flexible HVAC system that can supply lower outdoor air rates when occupancy is lower than the design value; densely occupied space (40 sq.ft. or less per person); HVAC systems; IAQ; ventilation; occupants; outdoor air; ppm = parts per million; return air is removed from a space; thermal comfort is subjective measure of satisfaction; ventilation; VOCs.

Intent: Improve IAQ (for more health, comfort, productivity) by providing more outdoor air.

Requirements: Two cases, the first for mechanically ventilated spaces; the second for naturally ventilated spaces. For Case 1, with mechanical ventilation, exceed outdoor air by 30% over prerequisite rates (based on ASHRAE 62.1-2007). For Case 2, with natural ventilation, there is a requirements and then 2 options. The requirement is to satisfy "Good Practice Guide 237" (1998) of the Carbon Trust; and to confirm that natural ventilation is appropriate per Figure 1.18 of Applications Manual 10:2005 (Natural ventilation in non-domestic buildings) of the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE). The 2 options are either: (1) Confirm with calculations or diagrams that the requirements of the CIBSE manual are met; or (2) Confirm that natural ventilation will satisfy ASHRAE 62.1-2007 ventilation rates for 90% of the occupied spaces, based on "macroscopic, multizone, analytic model" for room-by-room airflow.

1. Benefits/issues. Balance between costs (installation plus energy) and user comfort/productivity. Consider heat-transfer devices so that fresh air is pre-heated or -cooled by return air leaving building.

[From Version 2.2 critique] This increased ventilation rate is admittedly lower than what research findings suggest would be necessary to achieve acceptable IAQ, i.e., 25 cfm/person ventilation rates, equivalent to an increase of 50% over the ASHRAE (and Credit 1) requirements. The LEED commentary admits that "30% was chosen as a compromise between indoor air quality and energy efficiency." In other words, one can get 2 LEED points for IAQ without adequately protecting occupant health. The idea that increased ventilation rates necessarily improve indoor air quality is however — and paradoxically — questionable. Joseph Lstiburek writes: "My insider's perspective (on Standard 62.2 at least) is that there is a lot of mileage to be made by scaring people about underventilation, and folks are rising to the occasion. Unfortunately, overventilation in hot, humid climates has led to more indoor air problems due to mold resulting from part-load issues than underventilation anywhere else... Doesn't anyone at the U.S. Green Building Council know anything about energy and part-load humidity?" (ASHRAE Journal, August 2008, p.64).

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. ASHRAE Standard 62.1-2007 and CIBSE Applications Manual 10-2005.

4. Implementation: Similar to prerequisite. The CIBSE Manual flow chart shows whether natural ventilation is feasible. To be a candidate for natural ventilation: a) Max heat gains no more than 30-40 W/m2 (or can be redesigned to that standard). b) Building has a narrow plan dimension or courtyards to reduce maximum dimension to about 15 m (45 ft). c) Outdoor noise and pollution levels are "acceptable" for opening windows. d) Occupants can "adapt conditions with weather changes" [not clear what this means].

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations. Similar to Prerequisite 1.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations. More practical for mild climates.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: air-conditioning; breathing zone; conditioned space; contaminants; exfiltration (indoor air leakage); exhaust air; HVAC; IAQ; infiltration; mechanical ventilation; mixed-mode ventilation (combines natural and mechanical modes); natural ventilation; off-gassing; outdoor air; recirculated air; supply air; ventilation.

Intent: Reduce IAQ problems due to construction process itself, while protecting occupants and construction workers.

Requirements: Make a plan to a) meet or exceed SMACNA IAQ guidelines for occupied buildings under construction [Sheet Metal and Air Conditioning National Contractors Association]; b) protect absorptive materials from moisture; and c) use MERV 8 filters at return grilles on any air handlers used during construction that are intended for the occupied building [MERV = Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value], per ASHRAE Standard 52.2-1999 (with errata but not addenda).

1. Benefits/issues. To ensure good IAQ, one must start during construction.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. SMACNA IAQ Guidelines for Occupied Buildings under Construction, 2nd edition, Ch 3, Nov.2007; (ANSI) ASHRAE Standard 52.2-1999 Method of testing general ventilation air-cleaning devices for removal efficiency by particle size.

4. Implementation: Make a plan, hold meetings, educate the contractors. In general, it is better to use temporary construction ventilation rather than using the final building system (which has implications for the system warranty). Seal all ducts and equipment during construction; or use temporary filters with MERV 8 or better. Then replace all filters just before occupancy. Control VOCs or other toxic materials. Clean up frequently; isolate spaces from those with contaminants.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: construction IAQ management plan; HVAC; IAQ; MERV ratings are established in ASHRAE 52.2-1999 and range from "minimum efficiency reporting values" of very low efficiency (MERV 1) to very high efficiency (MERV 16).

Intent: Reduce IAQ problems due to construction process itself, while protecting occupants and construction workers.

Requirements: Two options. Either: (1) Flush out the building by ("path 1") providing new filters just before occupancy and supplying 14,000 c.f. outdoor air per sq.ft. floor area at internal temperature of min. 60 degrees and max. relative humidity of 60%; or ("path 2") spread out the flush-out air before occupancy (3,500 c.f. outdoor air per sq.ft. floor area) and during occupancy (greater of 0.30 cfm per sq.ft. of building area -- not outside air as written -- or design min. rate per Prerequisite 1) beginning each day 3 hours early until the total outside air volume of path 1 is reached; OR (2) Actually test the air per EPA Compendium of Methods for the Determination of Air Pollutants in Indoor Air as modified in these LEED guidelines. Then flush-out only as needed to bring contaminated areas into compliance, as follows:

* the test for 4-PCH is only done if carpets/fabrics with styrene butadiene rubber (SBR) latex backing are used.

Movable partitions/workstations should be in place but don't have to be. Sample at rate of 1 sample per 25,000 sq.ft. of contiguous floor area for each part of the building with a separate ventilation system (which should be operating in the normal manner, but without occupants). Sample in breathing zone (3-6 ft. above floor) and for 4-hr. minimum time period.

1. Benefits/issues.

[From Version 2.2 critique] The LEED rationale for improving IAQ is that increasing worker productivity translates to "greater profitability for companies…" at least relative to those businesses that prefer to save energy by supplying stale air to building occupants. This trade-off between energy cost and indoor air quality is made explicit elsewhere in the LEED guidelines, so that the claim here that IAQ improvements, in and of themselves, lead to "greater profitability" is contradicted by the admission that the added costs of heating and cooling fresh air may outweigh any productivity gains. The idea that increased IAQ necessarily leads to greater productivity is also questionable, especially where workers do not get paid sick leave (this includes approximately half of all full-time private sector workers in the U.S.). When sick workers don't get paid, productivity (a measure of output per amount invested) doesn't necessarily suffer, since either remaining workers will pick up the slack (actually increasing productivity), or temporary workers will fill in (leaving productivity unchanged).The suffering of workers — admittedly increased by conditions of poor air quality — cannot simply be equated with reduced productivity of capital.

Even where a certain allowance is made for sickness (e.g., company policies or legislation mandating a certain number of "sick days"), this simply becomes the new "baseline" factored into business calculations; in this context as well, improved worker health due to improved IAQ does not necessarily translate into increased rates of output (productivity). Studies that purport to show productivity gains due to increased indoor air quality are often flawed, in that they do not actually measure productivity, but rather measure health improvements which are then carelessly extrapolated into productivity claims. For example, given a potential reduction in respiratory illness of 9% to 20% based on improved indoor air quality, one scholarly study [PDF] concludes that "16 to 37 million cases of common cold or influenza would be avoided each year in the US. The corresponding range in the annual economic benefit is $6 billion to $14 billion." This so-called "benefit" is calculated by multiplying the average wages of the workers studied (apparently $375 per sickness) by "16 to 37 million" incidents of colds or flu per year. But it is not at all clear that this "benefit" is lost, or, if it is lost, who the loser is: to repeat the point made above, when sick workers are not paid, productivity may actually increase (as fellow workers pick up the slack), or at least stay more or less the same as replacement workers are hired.

Another criticism of productivity claims — according to Anne Whitacre's letter in the February 2008 issue of The Construction Specifier — is that "worker productivity goes up when employees move to a new office space, but that the result is often short-lived." She concludes that "since most green buildings have been around for less than five years, any long-term studies of costs and productivity are simply not yet available." I haven't been able to independently confirm this claim.

Practices that damage worker health have always been perfectly compatible with both productivity and profitability (see, for example, this NY Times Op Ed by Susan J. Lambert from Sept. 19, 2012). It is always state intervention (40-hour week, child labor laws, and so on) that establishes the baseline conditions for acceptable damage to worker health, compatible with growth of the economy as a whole. While it may be true that competition for the highest-level elite workers impels owners in such industries to offer higher-quality interior environments, low levels of indoor air quality for the rest of the work force threaten neither productivity nor profitability.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. EPA Compendium of Methods for the Determination of Air Pollutants in Indoor Air.

4. Implementation: Flush-out can use the HVAC system, but also a temporary system (fans in windows) works if it meets the temperature and humidity requirements. Note that minimum flush-out rate of 0.3 cubic feet per minute per sq.ft. of building area (Option 1, path 2) may exceed the capacity of the HVAC system; this needs to be considered during the design phase.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations. As described above.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations. In certain more extreme climates, the flush-out could be more problematic, so scheduling during appropriate seasons is a consideration.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: construction IAQ management plan; contaminants; HVAC; IAQ; off-gassing; outdoor air; thermal comfort; ventilation.

Intent: Reduce IAQ problems due to odorous, irritating, or harmful contaminants (for both occupants and construction workers).

Requirements: This applies only to newly applied sealants and adhesives on the inside of the buildings weatherproofing system. South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD) Rule #1168 governs adhesives, sealants and sealant primers; VOC limits are based on rule amendment date 1/7/05 and are expressed in g/L units (after subtracting water). Green Seal Standard for Commercial Adhesives GS-36 (effective 10/19/00) governs aerosol adhesives* and the units are in VOC percentage by weight.

1. Benefits/issues. VOCs are bad for occupants and for the environment (smog, air pollution). Some low-VOC materials are more expensive or hard to find.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD) Rule #1168 governs adhesives, sealants and sealant primers; VOC limits are based on rule amendment date 1/7/05 and are expressed in g/L units (after subtracting water). Green Seal Standard for Commercial Adhesives GS-36 (effective 10/19/00). See requirements above.

4. Implementation: Applies to all surfaces in contact with indoor air, including furnishings and material above suspended ceilings, and inside wall/floor cavities. Includes caulk in windows and wall/ceiling cavity insulation.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations. Aside from absolute limits on VOC content in each material, it seems possible to exceed certain VOC guidelines for individual elements, as long as the total "VOC budget" is maintained. In this case, calculate the totals used by multiplying g/L times number of liters (volume) for both the "baseline" and "design" cases and compare. The baseline application rate should not exceed the design rate (this stipulation is unclear...).

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: adhesive; aerosol adhesive (include spray adhesives, mist spray, and web spray); etc.; ozone = O3, usually created as chemical reaction between VOCs and NOx in sunlight; VOC.

Intent: Reduce IAQ problems due to odorous, irritating, or harmful contaminants (for both occupants and construction workers).

Requirements: For "architectural" paints and coatings applied inside the waterproofing "envelope" of the building, meet Green Seal Standard GS-11 (Paints, 1st edition, May 20, 1993) VOC limits; for anti-rust/corrosive paints used on ferrous metal, meet Green Seal Standard GC-03 (anti-corrosive paints, 2nd edition, Jan. 7, 1997) VOC limit of 250 g/L; for wood finishes (stains, primers, shellacs, etc.), meet South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD) Rule 1113 (Architectural coatings, in effect Jan. 1, 2004) VOC limits

1. Benefits/issues. Same as for prior credit: VOCs are bad for occupants and for the environment (smog, air pollution). Some low-VOC materials are more expensive or hard to find.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. Green Seal Standards GS-11 (architectural paints) and GC-03 (anti-corrosive/rust paints). South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD) Rule #1113 governs wood and other finishes and has a set of effective dates for various types of finishes. The current effective dates (and VOC limits) for a sample of selected finishes from LEED Table 1 are as follows:

* g/L minus water and exempt compounds

4. Implementation: Same as prior credit.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations. Same as prior credit.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: anticorrosive paints (used to prevent corrosion of ferrous metals); coating; contaminants; IAQ; paint ("liquid, liquifiable, or mastic composition that is converted to a solid protective, decorative, or functional adherent film after application as a thin layer"; primer (applied to substrate so that next coating sticks better); VOC.

Intent: Reduce IAQ problems due to odorous, irritating, or harmful contaminants (for both occupants and construction workers).

Requirements: Two options. Either:

(1) Comply with the following standards for appropriate material:

[alternative path: all non-carpet finished flooring meets FloorScore criteria and must be min. 25% of finished floor area.] | |

* includes vinyl, linoleum, laminate, wood, ceramic, rubber flooring and base

OR

(2) All floor materials may meet the California Dept. of Health Services Standard Practice for the Testing of Volatile Organic Emissions from Various Sources Using Small-Scale Environmental Chambers (with 2004 addenda).

1. Benefits/issues. Same as for prior credit: VOCs are bad for occupants and for the environment (smog, air pollution). Some low-VOC materials are more expensive or hard to find.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. Carpet and Rug Institute (CRI) Green Label Plus Testing Program; South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCQMD) Rule 1168 (VOC limits) and Rule 1113 (Architectural coatings); FloorScore program of the Resilient Floor Covering Institute (RFCI); California Dept. of Health Services Standard Practice for the Testing of Volatile Organic Emissions from Various Sources Using Small-Scale Environmental Chambers (Standard 1350, Section 9).

4. Implementation: Same as prior credit.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: contaminants; hard surface flooring; indoor carpet systems; IAQ; occupant; VOC.

Intent: Reduce IAQ problems due to odorous, irritating, or harmful contaminants (for both occupants and construction workers).

Requirements: Fixtures, furniture and equipment are not counted here. The credit applies to particleboard, medium-density fiberboard (MDF), plywood, wheatboard, strawboard, panel substrates and door cores used inside the building weatherproofing, and requires that no added urea-formaldehyde resins are included either in the product, or in laminating adhesives used either on site or in the shop.

1. Benefits/issues. Same as for prior credit: VOCs are bad for occupants and for the environment (smog, air pollution). Some low-VOC materials are more expensive or hard to find.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. Carpet and Rug Institute (CRI) Green Label Plus Testing Program; South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCQMD) Rule 1168 (VOC limits) and Rule 1113 (Architectural coatings); FloorScore program of the Resilient Floor Covering Institute (RFCI); California Dept. of Health Services Standard Practice for the Testing of Volatile Organic Emissions from Various Sources Using Small-Scale Environmental Chambers (Standard 1350, Section 9).

4. Implementation: Same as prior credit.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: agrifiber board (composite material from agricultural waste fiber, e.g., cereal straw, sugarcane bagasse, sunflower husk, walnut shells, coconut husks, etc.); composite wood (wood fibers bonded using synthetic agent, including plywood, OSB, etc.); contaminants; formaldehyde (naturally-occurring VOC Ð carcinogen and irritant); indoor composite wood or agrifiber; IAQ; laminate adhesive; off-gassing; urea-formaldehyde (combines formaldehyde and urea to make glue; can emit formaldehyde at room temperature); pheno-formaldehyde (used in exterior glues, off-gasses only at high temperatures, and can be used in interior applications).

Intent: Reduce IAQ problems due to particulates and chemical pollutants.

Requirements: Don't let pollutants indoors by doing these 4 things:

Provide 10 ft. long entryway dirt/particulate-capturing grate, grill, etc. that can be cleaned underneath (mats OK if cleaned weekly).

Exhaust those spaces that generate pollutants such that negative pressure is established relative to adjacent occupancies (garages, print rooms, laundry, etc.), at least when the door is closed. Specifically: 0.5 cfm exhaust to create average 5 Pa pressure difference and 1 Pa with closed doors. Floor-to-deck partitions and self-closing doors (optional) also needed.

Provide MERV 13 filters for return air and supply-outside air installed before occupancy.

Store chemical-mixing hazardous liquid wastes in "regulatory compliant" storage area (outside if possible for, e.g., science lab, janitorial).

1. Benefits/issues. May cost more money, but it's important.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. (ANSI) ASHRAE Standard 52.2-1999 Method of Testing General Ventilation Air-Cleaning Devices for Removal Efficiency by Particle Size.

4. Implementation: For entryway systems, exceed Fire-retardant ratings DOC-FF-1-70 (such as NFPA-253 Class I and II); have electrostatic propensity level less than 2.5 kV. Convenience printers/copiers excluded from this credit.

6. Calculations.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples. See diagram, PDF p.544.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations. Could affect type of entryway system.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: air-handling units; entryway systems; IAQ; MERV; regularly occupied space; walk-off mats.

Intent: Let individuals or groups control lighting levels to improve their comfort and productivity.

Requirements: Do 2 things: a) make available lighting controls for 90% of occupants for their individual tasks; and b) make available controls in multi-occupant spaces that can be adjusted by the groups using the spaces.

1. Benefits/issues. Better for productivity, comfort, and flexibility (different tasks), plus saves energy (less heat generated, less light needed) with a strategy of low ambient light throughout and task lighting for individuals. But has potential to waste electricity if lights are uncontrolled by sensors, or occupants are not properly educated about the system. Strategic reflective/non-reflective surface design can reduce number of required fixtures.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards.

4. Implementation: Strategy is repeated (general ambient with task lighting). Task lighting should have some controls to automatically turn off (or turn on), and should itself be adjustable. Design should meet IESNA illumination standards (Illuminating Engineering Society of North America). High contrast between illumination levels in different areas not good.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations. For 90% requirement, the minimum control is on-off; but it is better to allow re-positioning, and adjustable light levels. Where daylighting is included, provide controls for darkening and for glare-reduction. Use light-colored ceilings 9-1/2 ft. above floor, 90% reflectivity.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations. Regions with "strong sunlight" can use passive design strategies, but need controls to mitigate against fluctuations.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: audiovisual media; commissioning = a verification/documentation process to make sure systems are operating as intended; controls; daylighting; glare; individual occupant spaces; nonoccupied spaces; outdoor air; group multi-occupant spaces; sensors.

Intent: Let individuals or groups control thermal comfort systems to improve their comfort and productivity.

Requirements: Do 2 things: a) make available individual comfort controls for 50% of occupants (this can consist of operable windows satisfying ASHRAE 62.1-2007 for occupants located within a rectangle 10 ft on either side of the window and 20 ft. away from the window); and b) make available controls in all multi-occupant spaces that can be adjusted by the groups using the spaces.

Note that ASHRAE Standard 55-2004 (yes errata, no addenda) describe the elements of comfort as air temperature, radiant temperature, air speed, and humidity.1. Benefits/issues. Better for productivity and comfort. Potential for abuse of individual controls, so occupant education important. Potential to upset the calibration of the HVAC system.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. ASHRAE 62.1-2007 Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality for natural ventilation requirements (e.g., 4% floor area for operable window area); ASHRAE 55-2004 Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy (for making 80% of occupants happy).

4. Implementation: Individual controls can consist of thermostats, or individual diffusers, or individual radiant panels. Sensors can turn down temperature and/or airflow when unoccupied.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

Example of variable volume air distribution on typical office floor

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations. Operable windows may not be appropriate in extreme climates, or where outside pollution levels are high.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: building envelope; comfort criteria; commissioning; controls; daylighting; HVAC; individual occupant spaces; natural ventiliation; nonoccupied spaces; outdoor air; regularly occupied spaces; group multi-occupant spaces; sensors; thermal comfort.

Intent: Make the environment comfortable for comfort and productivity.

Requirements: Meet ASHRAE Standard 55-2004 (yes errata, no addenda) Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy for HVAC systems and building envelope (compliance documentation section 6.1.1 must also be followed).

1. Benefits/issues. Better for productivity and comfort. The envelope can be especially important for the comfort of occupants on the perimeter, as well as for lowering energy costs. Combinations of natural and mechanical ventilation may cost less to build and to operate.

[From Version 2.2 critique] The contradiction ("challenge") of reducing energy while promoting indoor air quality is acknowledged in the LEED guidelines, but not resolved. Energy and IAQ are, in fact, linked; yet LEED allows them to be treated independently. There is no penalty under the LEED guidelines for choosing to save energy at the expense of indoor environmental quality. At the extreme, even if none of the 12 EQ credits [now 15 points possible in "IEQ" credits in 2009 version] are complied with, there are still plenty of points left for platinum certification.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. ASHRAE 55-2004 Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy (for making 80% of occupants happy); CIBSE (Chartered Institute of Building Services Engineers) Applications Manual 10-2005 Natural ventilation in non-domestic buildings (British standard).

4. Implementation.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations. No calculations, but provide description of how comfort is achieved.

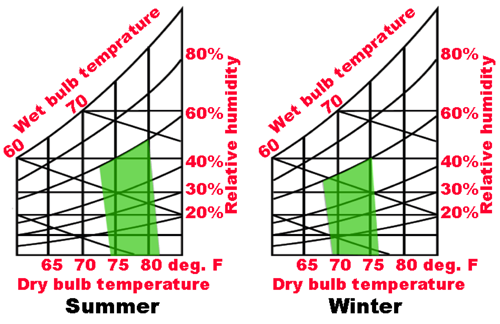

Psychometric charts show summer and winter "comfort zones"

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples. Comfort determined not only by building design (temperature, humidity, etc.) but also by occupancy and occupants (metabolic rate, clothing). Psychometric charts show comfort zone relative to temperature and humidity. (See PDF page 568, 569)

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations. Especially important when natural ventilation is used; also expectations of indoor comfort are related to outdoor conditions.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: comfort criteria; commissioning; mechanical/natural ventilation; mixed-mode ventilation; occupants; predicted mean vote (to rate thermal comfort subjectively); relative humidity (partial density of vapor divided by saturation density at same temperature and pressure); thermal comfort.

Intent: Verify occupant thermal comfort.

Requirements: Anonymously survey occupants 6-18 months after occupancy to determine satisfaction with thermal conditions; promise to make corrective plan if more than 20% responses are negative (measured per ASHRAE 55-2004); and create a "permanent monitoring system" to assure than the criteria in IEQ Credit 7.1 are met. Residential projects cannot get this credit.

1. Benefits/issues. Complaints about thermal comfort should be addressed, even if energy costs rise as a result.

[From Version 2.2 critique] A survey conducted six months after occupancy will not necessarily reveal thermal problems that are seasonal in nature, e.g., overheating in the summer, or cold indoor temperatures in the winter. It will also not guarantee that building operators will maintain adequate comfort levels in the years after such a survey is conducted.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. ASHRAE 55-2004 Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy (for making 80% of occupants happy).

4. Implementation. Must satisfy IEQ Credit 7.1 to get this credit. Survey should have 7 point scale with 3 levels of "satisfied" and 3 levels of "unsatisfied" (0 being the neutral point), where any of the "unsatisfied" levels counts in the measure of dissatisfaction. Lighting/acoustics questions may be included, but are not required.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

9. Exemplary performance. N/A

10. Regional variations. Especially important when natural ventilation is used; also expectations of indoor comfort are related to outdoor conditions.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions (same as IEQ Credit 7.1): comfort criteria; commissioning; mechanical/natural ventilation; mixed-mode ventilation; occupants; predicted mean vote (to rate thermal comfort subjectively); relative humidity (partial density of vapor divided by saturation density at same temperature and pressure); thermal comfort.

Intent: Make indoor-outdoor "connection" consisting of daylight and outdoor views.

Requirements:

There are 4 options for providing 75% regularly occupied spaces with daylight:

(1) Using computer simulation: required illumination levels between 25 and 500 fc (footcandles) in clear sky, Sept. 21 at 9am and 3 pm, with "view-preserving" glare-control devices OK as long as min. 25 fc is maintained.

(2) Using a prescriptive method: VLT x WFR = daylight zone between 0.150 and 0.180; where VLT is visible light transmittance and WFR is window-to-floor area ratio, with window area used no less than 30 in. above floor. Other criteria apply: the triangular zone in front of the window making an angle with the floor of tan-1(1/2) must be unobstructed; some sort of "redirection" or glare control must be provided.

For skylights (top-lighted daylight zones), the daylight zone extends beyond the "footprint" of the skylight by the lesser of 0.7 x ceiling height (35 degrees from vertical), or half the distance to the next skylight, or distance to a partition "farther than 70% of the distance between the top of the partition and the ceiling" (i.e., to any partition interrupting the 35-deg. envelope); between 3-6% of roof area is skylit with minimum VLT of 0.5; distance between skylights no more than 1.4 x ceiling height; any skylight diffuser must have "measured haze value" more than 90% per ASTM D1003 with no direct line of sight to the diffuser (see PDF page 579 for diagram).

(3) Using measurement: Prove by measurement on 10-ft. grid that 25 fc is achieved (no times, dates specified here). Use glare-control as needed.

(4) Using combination of above methods. Use glare-control as needed.

1. Benefits/issues. Can reduce need for electric lighting (up to 50-80%). Need to balance heat loss/gain, glare, fluctuations. Consider various shading devices, light shelves, atriums, courts, interior finishes (reflectance). Avoid bird collisions. Costs offset by increased productivity.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards. ASTM D1003-07e1 Standard test method for haze and luminous transmittance of transparent plastics.

4. Implementation. Shallow floor plates help, or courts, atriums, skylights, clearstories. (see PDF diagram p.581) Automatic controls are possible to balance electric and daylight. Bird-collision control measures: exterior shading devices, fritted glass or etched patterns; differentiated materials, etc. to fragment reflective patterns, reducing apparent area of transparency or reflectivity. Glare-control measures: exterior shading devices, light shelves (inside or out), blinds/louvers/draperies, fritted glass, "electronic blackout glazing."

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations. Explain if any areas should be excluded (because daylighting hurts their functionality). Any area within a room that has at least 25 fc counts, but exclude any portion of room area that is noncompliant.

Option 1. Simulation: 5-ft. grid for measurement at work-level height (e.g., 30 in. above floor). Use equinox date (Sept 21 or March 21 at 9 am and 3 pm) and clear skies. Need glare control for each window. Establish min. (25 fc) and max. (500 fc) for any space that is counted; divide areas of acceptable spaces by total area to see if the 75% criteria is met.

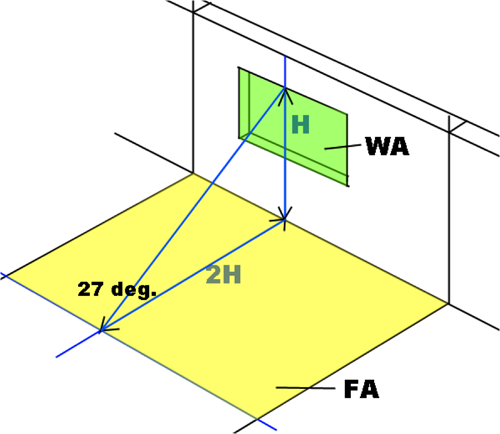

Option 2. Prescriptive. For side lighting in conventional conditions, take typical bays for each orientation, and corners. [this seems to apply to typical curtain walls with continuous strip windows?]

Find WA (window area) for a bay (only counting window area 30 in. above floor).

Find FA (floor area) by drawing 63-deg. triangle (so tangent = 1/2) from highest point on glass resulting in unobstructed line.

Find window-floor ratio (WFR) = WA/FA

Determine if VLT (visible light transmittance, now called Tvis) x WFR falls between 0.150 and 0.180 for ALL bays in the building.

Establish glare control measures (blinds, light shelves, etc.)

Prescriptive method calculations for daylighting based on window-floor ratio

For top-lighting: make sure skylight diffuser is more than 90%; confirm skylight roof coverage minimum; find daylight zones and confirm area is at least 75% of total occupied area.

Option 3. Measurement. Only count the portions of rooms actually conforming to the requirements. Deal with glare. Measure at task height (e.g., 30 in. above floor) on 10-ft. grid. Need 25 fc minimum to comply.

Include multipurpose rooms, but for dedicated theatres, only 10 fc is required.

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples.

9. Exemplary performance. Yes, if 95% occupied space meets criteria.

10. Regional variations. Region influences light potential and seasonal variations.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: daylighting; daylighting zone (meets criteria outlined in this credit); glare (excessively bright light creating discomfort or problems with seeing); regularly occupied space; visible light transmittance (Tvis = ratio of transmitted light to incident light; light meaning visible light); vision glazing is defined as portion of glazing between 30 and 90 in. above floor permitting a view to the outdoors; WFR (window-to-floor ratio) is measured using all window area above 30 in. and floor area (extent of floor area not defined here).

Intent: Make indoor-outdoor "connection" consisting of daylight and outdoor views.

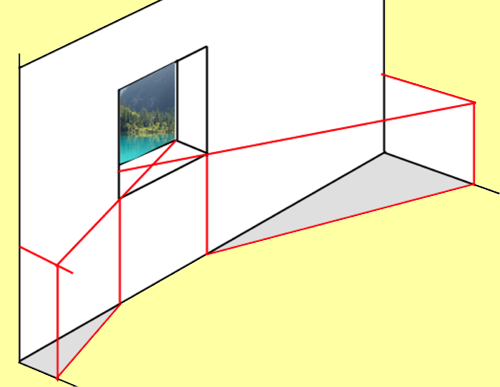

Requirements: 90% of regularly occupied area must have sight line to the outdoors, even if through 2 interior glazing planes. Must satisfy both plan and sectional criteria, where view must be through "vision glazing" between 30 and 90 in. above floor. An entire office area is counted if 75% of its area has a direct line of sight.

Determination of sight lines for view (plan criteria)

Determination of sight lines for view (sectional criteria)

1. Benefits/issues. Rationale for providing views and daylighting, in spite of relative energy inefficiency of glazed areas compared to solid walls, is that it increases productivity. Also, there may be an energy saving due to reduced need for electric lighting.

2. Related credits. Yes.

3. Referenced standards.

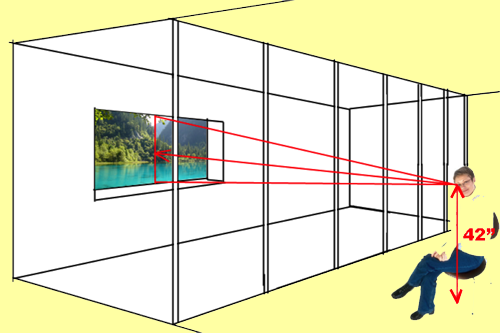

4. Implementation. Average seated line of sight begins 42 in. above floor for adults. Watch out for bird collisions.

5. Timeline and team.

6. Calculations. Create spreadsheet listing each space with the corresponding area that meets the sightline criteria based on plan view (with offices counting entirely if 75% of the area works). Then list "yes" or "no" based on meeting the sectional criteria, assuming a seated person with 42 in. above floor eye level. Only count those areas (based on plan) that meet the ("yes") criteria in section. Divide by the total appropriate area to test compliance for this credit (need 90%). (see diagrams on PDF pp. 595-6)

7. Documentation guidance.

8. Examples. In the example shown, the plan view angle through the glazed area considers the actual wall thickness for punched windows.

9. Exemplary performance. Yes, if any 2 of these 4 criteria are met:90% spaces have more than 1 line of sight at least 90-degrees apart;

90% spaces can see 2 of these 3 things: vegetation, human activity; objects 70 feet away from the glass;

90% spaces can see views "within the distance of 3 times the head height of the vision glazing";

90% spaces have view factor of at least 3 (per Heschong Mahone Group study, Windows and Offices, p.47).

10. Regional variations. Region influences heat loss and gain through vision glazing.

11. Operations/maintenance.

12. Resources.

13. Definitions: daylighting; direct line of sight to perimeter vision glazing; glare; regularly occupied spaces; vision glazing.

First posted 1 July 2010; last updated 21 September, 2012 [added link to NY Times Op Ed]