Jonathan Ochshorn

© 2014 Jonathan Ochshorn.

Following is my summary and critique of the USGBC's LEED Building Design & Construction Reference Guide, v4 [with bracketed comments on version 4.1 beta]. Commentary on the Reference Guide can be found in these red boxes, sometimes within each of the chapter links immediately above, but also in my summary and critique of the prior versions: Version 2.2 NC and Version 3.0.

This section was previously part of the "sustainable sites" category, but has now achieved independence. It values and rewards "thoughtful decisions about building location," placing a premium on site density and diversity, along with something called "alternative" transportation (presumably anything other than private gasoline-powered automobiles).

Granting independence to this subsection has two immediate benefits. First, it creates a category analogous to the "LEED for Neighborhood Development" rating system, thereby facilitating the automatic achievement of credits for projects located within such "neighborhoods." Second, it separates the two contradictory imperatives of "urban density" and "open space," both of which are validated within the LEED guidelines: but instead of having the credits for these contradictory practices uneasily linked within the same "sustainable sites" category, they are now placed in different sections. Of course, nothing is done to resolve the contradiction, but perhaps the folks at USGBC hoped no one would notice if the two credits were placed farther apart...

The premise that developing new buildings within established urban areas is somehow a "sustainable" practice is taken as self-evident within the LEED guidelines. In fact, new building always puts more of a strain on resources (materials needed to build the new building and demolish what was previously there), energy, and infrastructure, especially to the extent that new building is correlated with growth, rather than with the mere replacement of existing buildings. LEED seems oblivious to the idea that unplanned and unlimited growth is, ipso facto, unsustainable. Yes, agriculture has gotten far more efficient as human population has increased, but — even from that standpoint — there are practical limits to what can be sustained on a single planet. Capitalist growth may well be economically sustainable, but such growth is, and has always been, damaging to human and environmental resources. This is because its only criterion for success is the accumulation of wealth, and because the competition to succeed in this manner demands the cheapest possible costs of production (e.g., burning coal to generate electricity). Apologists for this type of activity love to point out that the harmful practices that they endorse are less harmful than other, more harmful practices that they identify: sure it's bad, but it's a lot better than what's going on in [fill in the country, or century]. They also point to profitable developments with "sustainable" attributes to prove that things are changing, as if providing better working conditions for certain high-end workers represents the leading edge of a new paradigm.

Intent: Reduce vehicle miles; avoid development on "inappropriate" sites; and encourage physical activity (walking and cycling).

Requirements: If the project is located in a development that is certified under LEED for Neighborhood Development, then the project can get 8 points (if certified), 10 points (if silver), 12 points (if gold), or 16 points (if platinum). However, if these points are taken, then no other points under the "Location and transportation" section can be taken, as they cover essentially the same ground. In some cases, it may be advantageous to eschew the points available through this credit and to take the individual points available in the other LT credits: like deciding whether to itemize or take the standard deduction on your taxes, the only way to know for sure is to calculate both scenarios and make a decision. The LEED Guide advises that, even in cases where more points are available by taking the individual credits, one must also consider the extra effort it would take to document all those credits versus the "as-of-right" (no documentation required) assignment of points under this credit.

Intent: Protect environmentally sensitive land from development.

It should be pointed out that the entire history of urban development would not have been possible if this LEED criteria were followed. It is therefore just a tad ironic that — in creating a rule that would have prevented all urban areas from even existing — this same rule actually encourages development in these very urban areas. It's like advocating for the rights of indigenous populations — after they've been effectively wiped out. The basic problem with this, as with many other LEED credits, is that all forms of social planning are eschewed; instead, all decisions are made by individual property owners, based on their own self-interest. With such an attitude, it is impossible to make rational decisions about the development of greenfields, brownfields, or any other parcels of land.

Requirements: There is really only one option — do not locate the project on undeveloped land unless it is not sensitive land: i.e., not prime farmland, in a floodplain, habitat for threatened or endangered species, within 100 feet of a water body, or within 50 feet of a wetland*. For some reason, this LEED credit provides another option, which is just a subset of the first: build on previously developed land.

This credit makes a mockery of all attempts at rational planning. Any piece of property can achieve points under this credit if it was previously developed, even if the prior (or proposed) development is environmentally damaging. On the other hand, so-called "sensitive" land cannot be developed under this credit, even if its development would be environmentally or socially useful. But don't worry: you can still get LEED points by developing greenfield sites in the next LEED section, under the Sustainable Sites "Protect or Restore Habitat" credit.

If the "property" contains sensitive areas, a project can still achieve this credit by avoiding the sensitive areas within the site.

* Note that the requirements for 100 foot and 50 foot buffers between a project and a water body or wetland are the reverse of the requirements in the 2009 LEED Reference Guide.

Intent: Encourage development in locations with what are euphemistically called "development constraints."

Requirements: There are two options worth 1 point, and a third option worth 2 points.

Option 1: For 1 point, the project must be in an available site within a historic district (i.e., one can't just tear down a historic building and replace it with your project; there must be a suitable "infill" site available — probably because someone else tore down the historically valuable building previously).

Option 2: For 1 point, the project must be in a site that is "sponsored" by various agencies — typically with financial incentives provided — such as the EPA National Priorities List, or a Federal Empowerment Zone, etc.

Option 3: For 2 points, the project must be on a brownfield site (with soil or groundwater contamination) where the required remediation is part of the project's scope of work.

Intent: Prioritize urban development (i.e., anti-sprawl) to protect greenfields, induce "physical activity," and so on.

Requirements: There are two options, both of which can be satisfied for a maximum of 5 points.

Option 1: For 2-3 points, locate in community with density of 22,000 square feet per acre (for 2 points) or 35,000 square feet per acre (for 3 points). Alternatively, density can be measured separately for residential (7 or 12 dwelling units per acre for 2 or 3 points respectively) and nonresidential (0.5 or 0.8 floor area ratio for 2 or 3 points respectively) development. As might be expected, there is a lot of fine print to define exactly what counts.

Option 2: For 1-2 points, locate within 1/2 mile of 4-7, or at least 8 (for 1 or 2 points respectively) "basic services," now called "existing and publicly available diverse uses" — e.g., bank, church, grocery, day care, cleaners, post office, museum, etc. Such acceptable uses are listed in LEED's Appendix 1 within five subcategories: food retail, community-serving retail, services, civic and community facilities, and community anchor uses (i.e., offices with at least 100 FTE jobs).

LEED allows office buildings that contain people who have "jobs" to count as a "diverse use," but not, for example, factories. Do the people who write these guidelines, and who presumably work in office buildings, believe that the only so-called "community anchors" where people might find employment are office buildings?

[From Version 2.2 critique] The LEED commentary suggests that such development improves worker productivity and occupant health: productivity because workers spend less time driving (as if workers somehow automatically live near their places of employment simply because a workplace is located within 1/2 mile of some residential area*; and as if workers with shorter commute times spend the "extra" minutes thereby obtained by arriving early at work and donating free labor to their employers); and health because of increased physical activity as people walk the 1/2 mile to the grocery store and carry back bread and pork chops to their homes (as if 1/2 mile walks seriously count as physical activity; and as if this small-town model of local grocery stores and daily walks to shop for fresh vegetables corresponds to actual life as we know it — this is clearly written by people who have never experienced the unrelenting exhaustion brought about by actually working, shopping, preparing meals, and raising families).

LEED introduces the concept of trade-offs here: the idea that there may be negative environmental consequences for following the advice leading to a particular credit. Specifically, the commentary notices that those who build in "dense" urban areas may encounter "limited open space and possible negative IAQ aspects such as contaminated soils, undesirable air quality or limited daylighting applications." But LEED has no mechanism for subtracting points corresponding to these, or other, potentially negative consequences of a particular development. Instead, each "credit" is considered independently, potentially leading to certification of a building that has numerous negative environmental features.

Note that maximizing urban development (high density) is rewarded here, while maximizing open space (low density) is rewarded elsewhere... The implicit argument that greenfields, unlike urban areas, should remain as undeveloped as possible only makes "sense" in the context of a planet carved up into parcels of privately owned real estate, each developed according to the calculations of its owner. Such a situation precludes examining the logic of consolidating development, even in greenfields.

Finally, LEED defends urban development by criticizing "sprawl," using two familiar arguments: first, commuters spend more time commuting (in cars), and may require additional cars to support their suburban lifestyles; second, by developing projects in cities, cities are restored and invigorated, which creates "a more stable and interactive community." Unfortunately, this second argument lacks historical perspective. It is precisely the congestion of urban areas that leads to the development of interstate highways and the redefinition of growth centered on the nodes created at the intersections of such highways (see Joel Garreau's 1991 Edge City). The ideal of living 1/2 mile from both one's workplace as well as "basic services" abstracts from the reality of work under capitalism: the city is useful precisely to the extent that physical proximity to a range of services and labor makes sense to a particular business; the attraction of such places to those who need to find work has a well-documented trajectory, but one that is entirely contingent upon the presence of businesses whose decisions to locate in a particular place have to do only with calculations concerning profitability. Whether workers move to follow jobs, or capital moves to reduce its costs, has nothing to do with supporting a "more stable... community." "Community" is a historically-bounded and unintended consequence of urbanization, neither its driving force nor its inevitable result. The suburban Desperate Housewives have as much sense of community as the urban Friends. Of course, both of these examples are fictional, but no more so than the "community" imagined in this LEED credit.

Note that a business may need to locate in an urban area for reasons that have nothing to do with preserving greenfields or fostering "community," and there may be no impact on "community" or on the preservation of greenfields (i.e., the nature of such a business may preclude development outside of urban areas so that greenfields, in any case, were never threatened) as a result of such development, yet the LEED credit is still awarded.

* The requirement that the project be no more than 1/2 mile from a residential development has apparently been deleted from the new v4 Reference Guide. The v4 Guide, however, retains the specious argument that urban density correlates with better health. This argument is made by referencing studies that show, for example, that "the probability of being overweight falls 5% for every half-mile (800 meters) walked per day." Of course, no evidence is cited showing that people in dense neighborhoods actually walk more than people in less dense neighborhoods, or are less overweight. In fact, it's easy to find evidence that the opposite is true — those in less dense rural neighborhoods are more physically active than those in urban areas. The relationship between urban density and weight (or activity) is hardly well-established, and much more nuanced than the LEED Reference Guide suggests. One study found that rural children were slightly more predisposed to be overweight than urban children, in spite of the fact that rural children were more likely to be physically active. More importantly, the study found that: "Minorities, children from families with lower socioeconomic status, and children living in the South experienced higher odds of being overweight." In other words, health and physical activity have very little to do with urban density, abstracted from questions of class and wealth.

Intent: Discourage use of cars (both from standpoint of pollution, global warming, and sprawl).

Requirements: Have building entrance within 1/4 mile walk of "bus, streetcar, or rideshare stops," or within 1/2 mile of "bus rapid transit stops, light or heavy rail station s, commuter rail stations, or commuter ferry terminals."

To qualify for points under this credit, one must meet thresholds for the minimum number of weekday and weekend trips. For "multiple transit types" including bus, streetcar, rail, or ferry, the requirements are as follows:

| Points | Minimum number of weekday trips | Minimum number of weekend trips |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 72 | 40 |

| 3 | 144 | 108 |

| 5 | 360 | 216 |

Where projects are served by only commuter rail or ferry service, the requirements are less severe, but the points gained are also reduced:

| Points | Minimum number of weekday trips | Minimum number of weekend trips |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24 | 6 |

| 2 | 40 | 8 |

| 3 | 60 | 12 |

Intent: Discourage use of cars (both from standpoint of pollution and sprawl), while promoting public health through physical activity.

Requirements: The project entrance (or bicycle storage area) must, first of all, be within 200 yards of a "bicycle network." This network must connect to either 10 "diverse uses," a school or "employment center" (where project floor area is at least half residential), or a mass-transit stop (bus rapid transit, rail, or ferry terminal — an ordinary bus stop doesn't count). The network must consist of designated lanes or trails, or ordinary streets where the speed limit doesn't exceed 25 mph. Depends on project occupancy. For commercial/institutional projects: provide "long-term" bike racks/storage for 5% of "regular building occupants" (with a minimum of 4 spaces) plus "short-term" storage for 2.5% of peak visitors (with a minimum of 4 additional spaces), along with shower/changing facilities, 1 for the first 100 occupants, and 1 more for each additional 150 occupants. For residential projects: long-term bike storage facilities for 30% occupants (but at least 1 space per dwelling unit) along with short-term storage for 2.5% of peak visitors (with a minimum of 4 spaces). Such storage must be within 100 feet of a main building entrance.

From my Critique of Milstein Hall (directly relevant to the LEED 2.2 Reference Guide, but mostly still applicable): LEED's bike-rack-as-sustainable-building-element credit is widely disparaged and ridiculed. However, the issue really isn't whether or not bike riding saves energy, reduces pollution, and encourages healthy life styles compared with car driving. All of these arguments are clearly valid. Whether the provision of bike storage is a "building energy" issue that belongs in a "green building" guideline at all might be a reasonable criticism if there existed a logical hierarchy of "green" standards that addressed sustainability at various scales—from the individual to the community to the entire planet. Given that no such mandates exist, it seems premature to unilaterally exclude bike racks from a green building guideline on this basis. Whether the credit given for provision of bike storage is consistent with the allocation of credits elsewhere in the LEED guidelines is actually impossible to determine, since simply providing a bike rack does not automatically cause people to stop commuting with cars, buses, or trains in any consistent manner. In other words, the real issue is whether providing bike racks and showers per the LEED specifications actually accomplishes any of the desirable goals for which bike use is properly credited.

At one extreme, one can certainly identify projects where either the program (e.g., luxury business hotel) or environmental conditions (e.g., unfriendly roads or steep hills with no provision or accommodation for bicycles) simply do not support cycling. Even the "LEEDuser" website suggests that providing bike racks in such circumstances may not be an efficient use of resources. But it seems clear that some building owners will install such bike racks for the cynical purpose of achieving a higher LEED certification level, even when the anticipated use of bike storage is uncertain or unlikely. [The v4 Guide addresses this problem to some extent by requiring that a "bicycle network" be available.]

At the other extreme one can find projects where a bike culture already exists, and where the provision of bike racks is not only necessary to support this existing culture, but where LEED specifications actually hinder bike usage by dramatically understating the actual need for such facilities. Such a condition applies to Milstein Hall at Cornell, where the LEED-recommended bike racks are woefully inadequate...

The cynical collection (purchase) of LEED points is hardly unusual; the bike rack credit serves as a prime example in Milstein Hall, not because bike use shouldn't be encouraged and supported for all the reasons mentioned above, but because neither the explicit goal of this credit—supporting bike use to reduce pollution, reduce reliance on non-sustainable fossil fuels, and support healthy life styles—nor even the straight-forward, if misguided, criteria for implementation of the credit—providing bike storage for 5% of the building's peak users and showers for 0.5% of the FTE population no farther than 600 feet from the building entrance—are met. Milstein Hall's expropriation of the Baker Lab shower is particularly egregious: I can state with some certainty that not a single Milstein Hall bicycle user is aware that such a shower exists, or has been informed that this shower has been made available to them (not that any of them would have the slightest interest in using it if they were made aware of its existence). Furthermore, the fact that this LEED credit was actually "earned" in Cornell's LEED design application, in spite of the fact that the criteria for the credit appear not to have been met, illustrates how the need to collect points in order to meet threshold requirements for a desired certification level (in this case, "gold") encourages a kind of sloppy (corrupt? cynical?) book-keeping where the points themselves become more important than actually understanding and creating the conditions for sustainable building.

Intent: Reduce environmental harm caused by parking facilities (includes "dependence" on cars, "consumption" of land, and stormwater runoff).

Requirements: Projects must provide less parking than is recommended by the Parking Consultants Council, as tabulated in Table 1 of the Reference Guide. How much less? In "dense urban areas," 40% less; otherwise 20% less. The actual criterion that distinguishes between these two reduction requirements is as follows: the 40% reduction is necessary if projects earn points under the "Surrounding density and diverse uses" or "Access to quality transit" credits. Otherwise, only a 20% reduction is required. In both cases, the project cannot exceed the required parking stipulated in the local zoning ordinance (improperly called the "local code" in the LEED Reference Guide).

Selected examples of parking space requirements from Table 1:

| Use | Number of parking spaces |

|---|---|

| College, university | 0.4/school population |

| Data processing | 6.0/1,000 square feet |

| Elderly housing | 0.5/dwelling unit |

| Health/fitness center | 7.0/1,000 square feet |

| Nightclub | 19/1,000 square feet |

| Office building (more than 500,000 square feet) | 2.8/1,000 square feet |

The rationale provided by LEED for reducing parking is based on a misreading of the reference that it cites. Here's what LEED says in its "Behind the Intent" introduction: "Parking lots' concrete and asphalt cover approximately 2,000 to 6,000 square miles (5180 to 15000 square kilometers) comprising about 35% of the surface area in the average U.S. residential neighborhood and 50% to 70% of the average nonresidential area." Now, anyone who has actually ventured out from their office cubicle and walked around city or suburban streets would realize immediately that such a high percentage of surface area devoted to parking lots does not exist in real places, except perhaps in shopping malls or along "strip" highway development. Here's what the reference that they cite actually says, right in the abstract: "In most non-residential areas, paved surfaces cover 50-70% of the under-the-canopy area. In residential areas, on average, paved surfaces cover about 35% of the area." In other words, the article is measuring total paved areas, including streets, sidewalks, and other hardscape — parking areas comprise a small percentage of the total paved area. How small? Well, Table 5 and Table 6 (based on data compiled for Sacramento ,CA) indicate that parking areas actually comprise 4.9% or 19.5% of residential areas, while Figure 5 indicates that the parking area for the entire Sacramento area is 12%. I cannot figure out what these various numbers mean, but the point is this: LEED completely misrepresents the article's conclusions by confusing parking area with total paved area. Clearly, making small reductions in the amount of parking area will have very little impact on the total paved area in cities.

LEED also misrepresents the cost of parking, stating: "Parking is expensive, costing landowners and developers an average of about $15,000 per space in the U.S." Once again, the reference cited by LEED contradicts this assertion, stating: "Overall, U.S. parking structure construction costs are reported to average about $15,000 per space or $44 per square foot in 2008, however this may include ground floor spaces which should not be counted." The key word here is "structure" (emphasis added). In other words, the $15,000 figure refers only to "structured parking" rather than ordinary on-grade parking. Of course, on-grade parking, which constitutes the overwhelming majority of parking in the U.S., is considerably cheaper than parking spaces within parking garages.

Intent: Reduce pollution (greenhouse gas emissions) by encouraging use of cars with alternative fuels.

Requirements: Projects must create 5% "preferred parking" (i.e., spaces close to the building entrance) exclusively for "green" vehicles (i.e., vehicles with a score of at least 45 on the rating guide of the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (ACEEE). Alternatively, green vehicle owners can be given a 20% discount on parking costs. In all cases, the project must also provide either electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE for 2% of parking spaces — this is Option 1) or liquid/gas alternative fueling or battery switching (with the capacity to handle 2% of the parking spaces — this is Option 2).

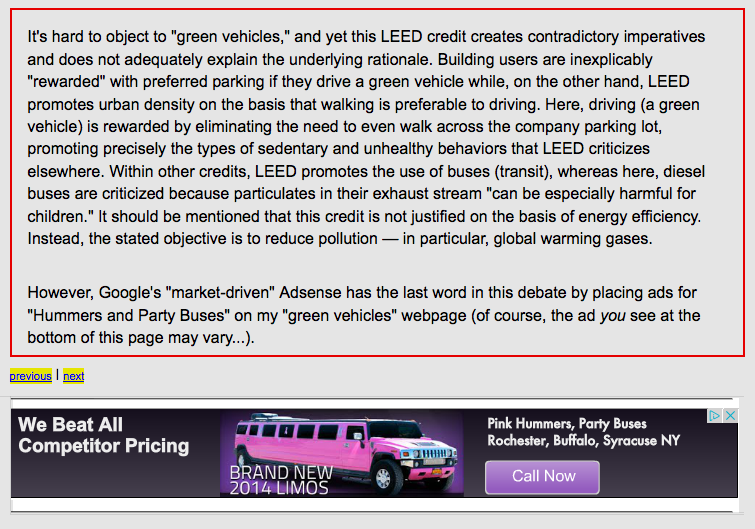

It's hard to object to "green vehicles," and yet this LEED credit creates contradictory imperatives and does not adequately explain the underlying rationale. Building users are inexplicably "rewarded" with preferred parking if they drive a green vehicle while, on the other hand, LEED promotes urban density on the basis that walking is preferable to driving. Here, driving (a green vehicle) is rewarded by eliminating the need to even walk across the company parking lot, promoting precisely the types of sedentary and unhealthy behaviors that LEED criticizes elsewhere. Within other credits, LEED promotes the use of buses (transit), whereas here, diesel buses are criticized because particulates in their exhaust stream "can be especially harmful for children." It should be mentioned that this credit is not justified on the basis of energy efficiency. Instead, the stated objective is to reduce pollution — in particular, global warming gases.

However, Google's "market-driven" Adsense has the last word in this debate by placing ads for "Hummers and Party Buses" on my "green vehicles" webpage (of course, the ad you see at the bottom of this page may vary...).

First posted 8 July 2014; last updated 10 February 2020