contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 19 |

20. SUSTAINABLE SITES

Construction Activity Pollution Prevention

Prerequisite 1. LEED requires all certified buildings to make a plan to reduce construction-related pollution and degradation (including soil erosion, dust). This is a fairly routine requirement, and is probably standard operating procedure in most municipalities even without the LEED incentive.

Site Selection

Credit 1. To get this point, the project cannot be built on farmland, undeveloped land in a flood plain, parks, habitats for threatened or endangered species, or undeveloped land within 50 feet (15.2 m) of water bodies. In other words, it would have been impossible for Milstein Hall not to get this point, except perhaps by extending its cantilevered floor plate another 150 feet (45.7 m) over the Fall Creek gorge.

This credit prioritizes development on previously developed land, even for sites within flood plains. This makes no sense from a rational planning standpoint, as there may well be instances where, for example, development on previously undeveloped land is sensible. However, such an analysis cannot occur when virtually the entire planet is divided into parcels under the control of individual owners seeking to exploit their property for private gain. In that context, rational planning becomes an oxymoron, and the stipulations of Credit 1 become entirely arbitrary. Why, for example, does building in a flood plain, or near a water body, become desirable simply because the site has already been inappropriately developed?1

Development Density & Community Connectivity

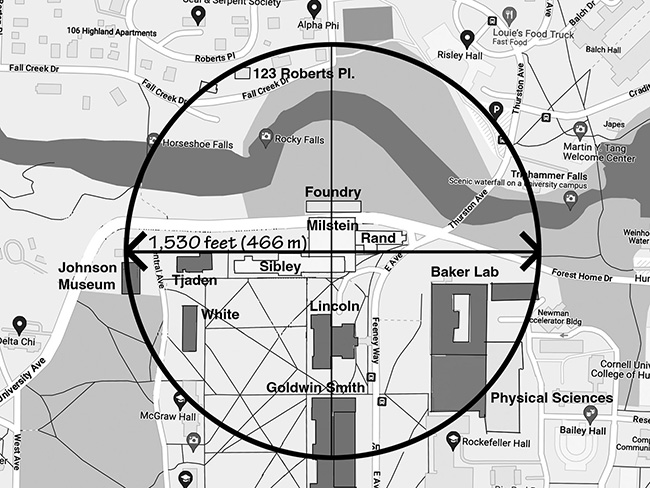

Credit 2. For this point, there are two choices, both of which require that the site has been previously developed (and Milstein Hall's site was previously developed, having supported both buildings and parking lots in the past). The first choice is to build in a location where the local building density is at least 60,000 square feet per acre (13,774 square meters per hectare), much like a typical two-story "downtown." Both the project on its own site, as well as the local density measured within a circle somewhat arbitrarily defined as having an area about 28 (actually 9 × π) times that of the building site, must meet this criterion (fig. 20.1).

Figure 20.1. Milstein Hall and its larger "urban" context: the circle represents an area approximately 28 times that of the building site.

If Milstein Hall has about 50,000 square feet (4,645 square meters) of program area and if its site, defined by the construction project limit line in the contract documents, has about 65,000 square feet (6,039 square meters), or 1.49 acres (0.60 hectare), then its density is 50,000 square feet / 1.49 acres = 33,557 square feet per acre (7,704 square meters per hectare), and does not meet the "downtown" criteria.2

For the larger "regional" density, we need to compute the total building area in a circle centered on the site with a radius of about 765 feet (233 m). Making gross assumptions about the building area on this regional site—i.e., assuming Baker Lab has 200,000 square feet (18,581 square meters); Sibley Hall has 54,000 square feet (5,017 square meters); Rand Hall has 27,000 square feet (2,508 square meters); and so on—we get a total building area of 855,000 square feet (79,432 square meters).

The regional site area is π × 7652 = 1,838,540 square feet, or 42.2 acres (170,806 square meters or 17 hectares). Therefore, the regional density is 855,000 square feet / 42.2 acres = 20,260 square feet per acre (4,651 square meters per hectare), which also does not meet the criterion. This is not particularly surprising since the Arts Quad at Cornell was not intended to be an "urban" space.

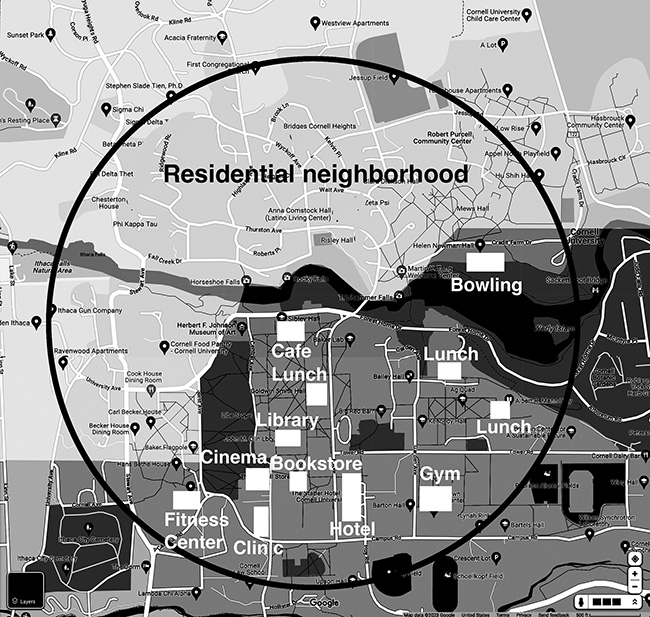

Luckily, there is another way to satisfy this credit. If the site is within 1/2 mile (0.8 km) of a residential area (Cornell Heights and Cayuga Heights, as well as all the Cornell dorms west and north of the site seem to qualify) and within 1/2 mile (0.8 km) of 10 "basic services" (things like banks, grocery stores, laundry, etc.), then you can still get the LEED point. As can be seen in figure 20.2, there is enough stuff within this 1/2 mile (0.8 km) radius actually on campus—including the Statler Hotel, Cornell Store, numerous eateries, fitness centers, and bowling—to satisfy the requirements for this LEED point.

Figure 20.2. Basic services and residential neighborhood within 1/2 mile (0.8 km) of Milstein Hall.

This credit idealizes urban density, which it correlates with sustainability, while at the same time prioritizing the exact opposite tendency in its open space initiatives (Credits 5.1 and 5.2). That points in both categories can be awarded to a single project—i.e., a project can maximize open space while achieving urban densities—demonstrates the futility of finding any coherence in the LEED guidelines. Furthermore, businesses may need to locate in an urban area for reasons that have nothing to do with preserving greenfields or fostering "community." In many cases, there is no impact on "community" or on the preservation of greenfields (i.e., the nature of such a business may preclude development outside of urban areas so that greenfields, in any case, were never threatened) as a result of such development, yet the LEED credit is still awarded. In the case of Milstein Hall, a point is awarded for "density" based on proximity to campus services like cafes and fitness centers which could not not have been awarded, given the decision to expand program facilities in that particular spot on campus. Is this a "sustainable" decision that deserves recognition (and points), when more resource-efficient schemes that would not involve new building construction at all, but rather would focus on improvements and modest additions to existing buildings, were not implemented? Such questions are never asked within the LEED rating system.

Brownfield Redevelopment

Credit 3. This point is only given to projects that remediate damaged sites. While this credit does not apply to Milstein Hall, it demonstrates an important problem with the LEED system. In virtually every section of the guidelines that explains how points are awarded, the LEED authors promote the notion that market forces ought to direct savvy business owners to sustainable practices. In other words, LEED is merely itemizing and rewarding practices that businesses would do on their own, without any recognition or certification, purely on the basis of self-interest—if only information about such practices was organized in a useful way. That this self-serving ideology runs counter to virtually the entire history of environmental practices is somehow not noticed: for wasn't it precisely the search for the best (most profitable) industrial and agricultural fuels that led to the use and abuse of first wood and then coal, gas, oil, and uranium? Back-and-forth pronouncements emanating from market-driven guardians of the environment like T. Boone Pickens demonstrate that the time for investment in wind energy is, or perhaps is not, now—depending, of course, on the relative cost of coal, oil, and gas.3

In the case of Credit 3, the LEED authors implicitly acknowledge that market forces would leave brownfields pretty much unremediated, since fixing them up is usually not a profitable practice. The LEED commentary references CERCLA (the 1980 Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, a.k.a. the "Superfund") which funds governmental intervention to remediate contaminated sites; the use of incentives at all levels of government is also mentioned as a way of encouraging "brownfield redevelopment by enacting laws that reduce the liability of developers who choose to remediate contaminated sites."4 From this, it is clear that sustainable development often does not make economic sense to businesses without state intervention (where such intervention takes the form of subsidies or is directly legislated as a specific requirement). And state intervention depends on competitive calculations of the state rather than on free-floating environmental ideals.

Alternative Transportation; Public Transportation Access

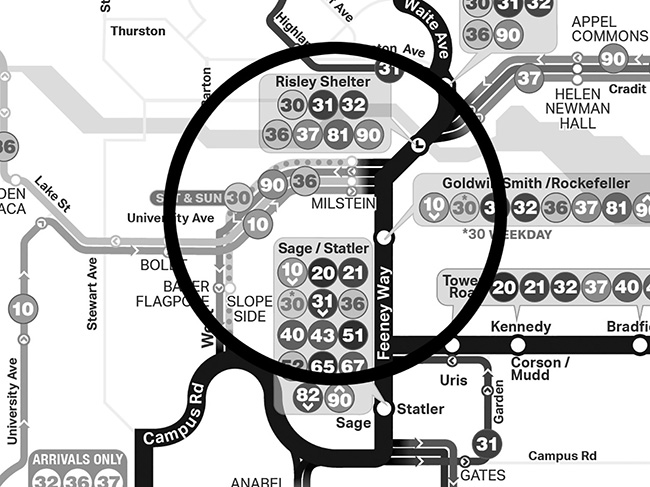

Credit 4.1. To get this point, the project needs to be within 1/2 mile (0.8 km) of a rail line—unfortunately, the campus-downtown trolley ceased operation in 1927—or to be within 1/4 mile (0.4 km) of at least two bus lines. Even with bus routes temporarily altered when they needed to detour around the Milstein Hall construction site, there were plenty of other routes within a 1/4 mile (0.4 km) radius (fig. 20.3), so Milstein Hall gets this point.

Figure 20.3. Bus route map showing plenty of stops within a 1/4 (0.4 km) mile radius of Milstein Hall.

Alternative Transportation, Bicycle Storage & Changing Rooms

Credit 4.2. This credit requires bike racks for 1/20 of the project's "peak" user population and showers for 1/200 of the building's full-time equivalent occupants. If we assume peak loads of 20 FTE (full-time equivalent) and 500 transients (this assumption is based on design phase programming estimates5), the required number of bike racks is 26, found by dividing 520 by 20. There appear to be about 22 spaces provided for bikes on Milstein Hall's dome (fig. 20.4), which seems insufficient.

Figure 20.4. Milstein Hall bike racks contain 11 semi-circular supports, presumably to accommodate 22 bikes, less than the 26 bike storage spaces required for a LEED point.

Additional bike storage is possible on the site if the guardrails adjacent to Sibley Hall are included; they are certainly used by students for this purpose, but it is unclear whether such use is sanctioned or unsanctioned. Certainly, the use of required handrails (fig. 20.5) for bike storage is unsanctioned.

Figure 20.5. LEED-recommended storage for 26 bikes is clearly inadequate for 520 bike-friendly building users. Here, unsanctioned bike storage takes place along ADA-required handrails.

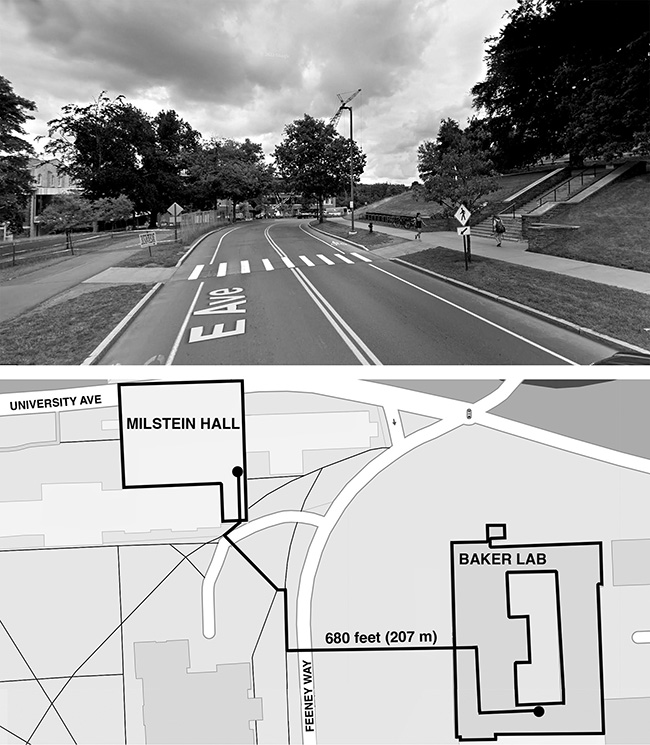

In any case, there are no changing rooms or showers in the building, which are required in order to get this LEED point. However, the fine print in the LEED guidelines permits campus buildings to share shower facilities, as long as the showers are no further than 600 feet (183 m) from the entrance to the building seeking certification. As it turns out, Baker Lab—a campus building diagonally across Feeney Way (formerly East Avenue) from Milstein Hall—has a single unisex shower on the second floor and on this basis Milstein Hall is claiming the bike rack credit. With only 20 FTE occupants of Milstein Hall (the remainder are classified as "transient"), this single shower would be more than enough to satisfy the mandate of 20 divided by 200, or 0.1 required showers. Unfortunately, the shower room is more than 600 feet from the entrance to Milstein (fig. 20.6) so this additional criterion for the LEED point is also not met. And even if the distance limit were overcome, the remote shower would not qualify since the hours of operation of the building it is in do not match the 24/7 operating hours of the architecture studios in Milstein Hall.6 In spite of this, Cornell has claimed the credit and LEED's reviewers have accepted the claim based on plans "provided showing the location of the shower/changing facilities and the bike storage facilities."7

Figure 20.6. The path from Milstein Hall's entrance to the LEED bike-point-required showers involves crossing Feeney Way, formerly East Avenue, and climbing the steps to Baker Lab (top); even so, the path distance exceeds the 600 feet (183 m) limit (bottom).

LEED's bike-rack-as-sustainable-building-element credit is widely disparaged and ridiculed, although there are some persuasive arguments in support of the credit.8 However, the issue really isn't whether or not bike riding saves energy, reduces pollution, and encourages healthy lifestyles compared with car driving. All of these arguments are clearly valid. Whether the provision of bike storage is a "building energy" issue that belongs in a "green building" guideline at all might be a reasonable criticism if there existed a logical hierarchy of "green" standards that addressed sustainability at various scales—from the individual to the community to the entire planet. Given that no such mandates exist, it seems premature to unilaterally exclude bike racks from a green building guideline on this basis. Whether the credit given for provision of bike storage is consistent with the allocation of credits elsewhere in the LEED guidelines is actually impossible to determine, since simply providing a bike rack does not automatically cause people to stop commuting with cars, buses, or trains in any consistent manner. In other words, the real issue is whether providing bike racks and showers per the LEED specifications actually accomplishes any of desirable goals for which bike use is properly credited.

At one extreme, one can certainly identify projects where either the program (e.g., luxury business hotel) or environmental conditions (e.g., unfriendly roads or steep hills with no provision or accommodation for bicycles) simply do not support cycling. Even the "LEEDuser" website suggests that providing bike racks in such circumstances may not be an efficient use of resources.9 But it seems clear that some building owners will install such bike racks for the cynical purpose of achieving a higher LEED certification level, even when the anticipated use of bike storage is uncertain or unlikely.

At the other extreme one can find projects where a bike culture already exists, and where the provision of bike racks is not only necessary to support this existing culture, but where LEED specifications actually hinder bike usage by dramatically understating the actual need for such facilities. Such a condition applies to Milstein Hall at Cornell, where the LEED-recommended bike racks are woefully inadequate.

The cynical collection (purchase) of LEED points is hardly unusual; the bike rack credit serves as a prime example in Milstein Hall, not because bike use shouldn't be encouraged and supported for all the reasons mentioned above, but because neither the explicit goal of this credit—supporting bike use to reduce pollution, reduce reliance on non-sustainable fossil fuels, and support healthy life styles—nor even the straight-forward, if misguided, criteria for implementation of the credit—providing bike storage for 5 percent of the building's peak users and showers for 0.5 percent of the FTE population no farther than 600 feet (183 m) from the building entrance—are met. Milstein Hall's expropriation of the Baker Lab shower is particularly egregious: I can state with some certainty that not a single Milstein Hall bicycle user is aware that such a shower exists, or has been informed that this shower has been made available to them (not that any of them would have the slightest interest in using it if they were made aware of its existence). Furthermore, the fact that this LEED credit was actually "earned" in Cornell's LEED design application, in spite of the fact that the criteria for the credit were not met, illustrates how the need to collect points in order to meet threshold requirements for a desired certification level (in this case, "gold") encourages a kind of sloppy (corrupt? cynical?) book-keeping where the points themselves become more important than actually understanding and creating the conditions for sustainable building.

Low-emitting and Fuel-Efficient Vehicles

Credit 4.3. There are several options to get this point, none of which are attempted or met by Milstein Hall.

Alternative Transportation, Parking Capacity

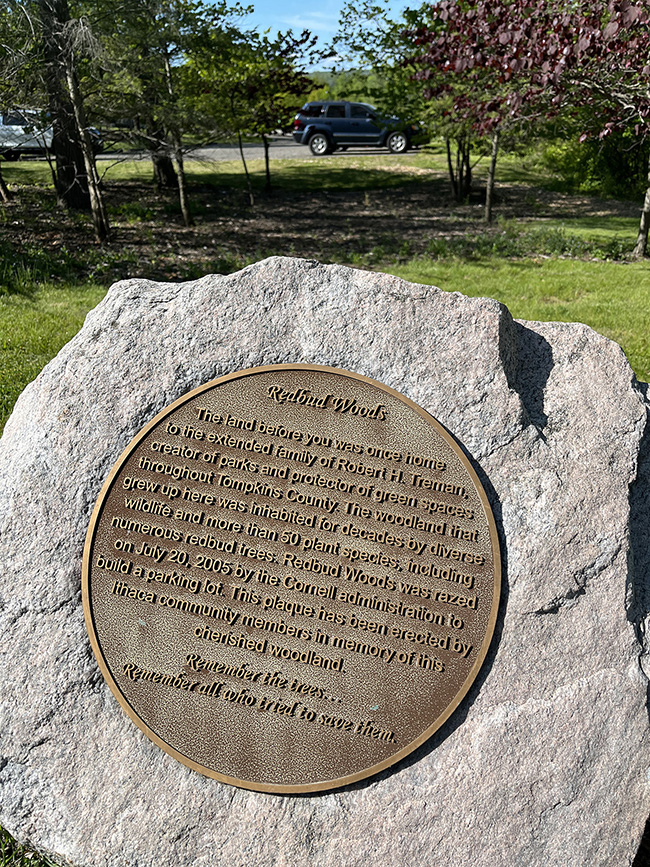

Credit 4.4. To get this point, you need to provide five percent of total parking as "preferred parking" for carpools or vanpools; or you need to provide no new parking for the project. Cornell has various programs to encourage carpooling, but none are directly tied to this project.10 Both structured underground and surface parking were originally planned adjacent to the Milstein site, but the underground component was cut in response to the financial crisis of 2008. Cornell had already cut down Redbud Woods in 2005 to build a new parking lot a few blocks from Milstein Hall, but this lot was not built specifically for any single building project. Remarkably, Cornell has used the case of Redbud Woods to demonstrate its commitment to a sustainable environment in an article that is no longer accessible online. After describing how Cornell successfully sued both the Ithaca Planning Board and the Ithaca Landmark Preservation Commission in order to overturn each of their independent rulings against the proposed parking lot, and after describing how Cornell Police arrested students engaged in a sit-in at the President's office and finally bought off students, faculty, and community members who had occupied the Redbud Woods site with a $50,000 sustainability research commitment and a memorial plaque (fig. 20.7), the article concludes that being sustainable is inherently contingent and unpredictable since "people value both cars and natural or historic lands."11

Figure 20.7. Cornell's Redbud Woods memorial plaque tells why and how a historic woods was bulldozed to create a parking lot: "The land before you was once home to the extended family of Robert H. Treman, creator of parks and protector of green spaces throughout Tompkins County. The woodland that grew up here was inhabited for decades by diverse wildlife and more than 50 plant species, including numerous redbud trees. Redbud Woods was razed on July 20, 2005 by the Cornell administration to build a parking lot. This plaque has been erected by Ithaca community members in memory of this cherished woodland. Remember the trees… Remember all who tried to save them."

Since parking on campus is often (always?) disengaged from particular buildings on campus, Cornell can claim that no new parking has ever been created for any building and in this way apply for a LEED point. The reality is different: buildings get built and parking gets increased on campus.

In fact, new underground parking next to Milstein Hall may well get built at some point: "Construction of an adjacent plaza will incorporate a turnaround for vehicles and access to an eventual parking garage on the site. The building of Milstein Hall will eliminate about two-thirds of existing parking space behind Sibley, 'with the hope that the parking garage will be built in the future, with more spaces than the existing parking lot'…"12

The "Alternative Transportation" credit provides LEED points even though it would be virtually impossible not to satisfy the listed criteria for this campus building. In the case of Milstein Hall, campus and city buses stop near the site, so the points for "public transportation access" are automatic, and have nothing to do with the building itself. I've also noticed that students often take these buses to get to classes that are only a half mile or so away, rather than walking or biking: is this really a "sustainable" (i.e., energy-conserving or health-encouraging) practice? Such buses also bring faculty and staff from "remote" parking lots to the central campus—again both encouraging car use while simultaneously discouraging the half mile walk from the remote lot. In other words, the ideology of "public transportation" obscures actual practices that discourage healthful and energy-conserving activity.

Site Development, Protect or Restore Habitat

Credit 5.1. To get this point for a non-greenfield site, at least half the site (not counting the building) needs to be planted with native or adapted vegetation. As most of the Milstein site is paved, this point appears not to be possible. Certain green roofs can, however, be counted in dense urban sites, in which case only 20 percent of the site area (including the vegetated roof area) needs be so planted. The vegetated roof plantings need to actually support a diverse range of birds and insects. While Milstein Hall is, apparently, a "dense urban site" (having earned Credit 2, Development density and community connectivity) and would seem to qualify for this site development point based on the size of its green roof, it may be that a lack of habitat diversity prevents Cornell from earning this LEED point: Milstein's vegetated roof appears to be more decorative than ecologically functional.

Site Development, Maximize Open Space

Credit 5.2. This credit can be satisfied in numerous ways, depending on zoning requirements for open space. Cornell University is governed by the City of Ithaca Zoning ordinance, which has a 35 percent maximum lot coverage for so-called U-1 (post-secondary) zones; in other words, there is a 65 percent open space requirement. LEED requires that vegetated open space exceed this zoning requirement by 25 percent. The Milstein site therefore would need 81.25 percent vegetated open space for this credit. Of course, Milstein Hall isn't really a "site" from the City's perspective; it is just one part of a larger campus for which the 35 percent maximum building area applies.

So, it isn't clear whether Milstein Hall gets this LEED point by meeting the 81.25 percent open space requirement on its own construction site, or rather by identifying some far-away campus green space, perhaps part of the Cornell Botanic Gardens, and assigning it as Milstein Hall's vegetated open space.

In the first case, and assuming that the site area is 65,000 square feet (6,039 square meters), the required vegetated open space is 0.8125 × 65,000 = 52,812 square feet (4,906 square meters). In reality, most of the open space on the site consists of a paved area to the west of Milstein Hall used for parking and vehicular service access. The small garden and other assorted green spaces account for only about 4,000 square feet (372 square meters)—this is an approximation; the actual green space may be a somewhat different—far short of the required vegetated area.

However, since Milstein Hall will presumably earn Credit 2 (Development Density & Community Connectivity) and will therefore count as an urban site in the eyes of LEED, it can get this point by providing up to 75 percent of required vegetated open space as "pedestrian oriented hardscape," and can also count the green roof as open space in this calculation. Because Milstein Hall's upper floor plate is raised above the ground plane, it may be possible to count the space under this floor as well as the area over this floor plate (the vegetated roof). In this way, Milstein Hall may well satisfy the requirements for this credit based on open space within its own site area.

In the second case, if it is determined that the City's zoning requirement for maximum lot coverage cannot be applied to the unofficial and ad hoc "site" area that has been designated for Milstein Hall's LEED calculations, then the credit can certainly be gained using LEED's remote-campus-open-space loophole.

The "Site Development" credit rewards habitat protection/restoration and open space, in contradiction to Credit 2 incentives for urbanity and density. But creating such bizarre incentives for individual parcels of land makes no sense in any case. Individual owners of property, acting in their own self-interest, simply cannot be expected to manage environmental conditions in a sustainable manner: first, the "environment" is a bit bigger than any individual land holding; second, the necessity for business owners to exploit their own property in order to compete successfully with other business owners (or for governmental entities to compete successfully with other governmental entities) makes environmental and health concerns just another line item in a cost-benefit calculation, not an end in itself.

Rather than confronting the true nature of capital and of environmental exploitation, the LEED commentary simply invents an imaginary world where business owners don't really care about the bottom line. For example, the LEED commentary's economic justification for open space is articulated as follows: "Even in cases where rent values are high and the incentive for building out to the property line is strong, well designed open space can significantly increase property values."13 This type of justification has no logical underpinning, in as much as the same premise could generate the opposite conclusion (i.e., it is equally plausible that in cases where rent values are high and the incentive for building out to the property line is strong, well designed open space—where such open space replaces otherwise rentable area—would significantly reduce property values).

The point is that real capitalist development is based on calculations to maximize profitability, where the provision of "open space" may or may not pay off for the developer. Furthermore, increasing the value of property is not the same as increasing profits: a developer can build an entire facade of gold bricks to create a building of extraordinarily high value while going broke at the same time. This is, in fact, exactly the case with Milstein Hall, which would certainly fall apart under its own financial weight were it not for the peculiar infrastructure of alumni and other benefactors who seem willing to subsidize such projects.

In its final submission for LEED review, Cornell claims that "the project has been developed in an area with zoning requirements, but with no requirement for open space…"14 This is inaccurate, since the requirement for 35 percent maximum lot coverage in its U-1 zoning district seems identical to a stipulation for 65 percent open space. In any case, the credit is easy to obtain for a building on a large campus with a vegetated roof.

Stormwater Design, Quantity Control

Credit 6.1. This credit requires that peak discharge rates of stormwater— water landing on the site from rain or snow—are reduced or controlled. Different criteria apply depending on the site's imperviousness; various strategies are suggested, including water retention facilities, harvesting and reusing rainwater, and so on. Milstein Hall, on the other hand, discharges virtually all stormwater from the site and so doesn't satisfy the criteria for this credit. Its vegetated roof, described in more detail below, is not particularly effective at reducing stormwater discharge during serious storm events.

Stormwater Design, Quality Control

Credit 6.2. To get this credit, 90 percent of an average year's stormwater must be captured and treated. Milstein Hall's green roof becomes saturated pretty quickly because it consists of only a few inches of growing media (one cannot really say "soil," as the medium is more like a fine gravel). A great deal of water falling on the green roof actually ends up finding its way to roof drains, coursing through enormous drainpipes that are visible within the building (fig. 20.8), and ending up in the storm sewer system, rather than being "captured" by the roof 's nominal growing medium or plantings, or directed into cisterns for use on site (there are none).

Figure 20.8. Milstein Hall's rainwater system originates in drains on the vegetated roof, courses through several large drainpipes, shown here in the second-floor studios, continues through the outer layers of the Crit Room dome (as shown in figure 2.6), connects into the regional storm sewer system under University Avenue, and finally is discharged, untreated, into Cayuga Lake.

This "Stormwater Design" credit encourages quality and quantity control of run-off from rainstorms. Like the site development credits discussed earlier, the underlying premise of dealing with such environmental issues on a site-by-site basis may, or may not, make any sense. In some cases, dealing with stormwater design on a larger regional scale may be more efficient, and more sustainable. Yet LEED has no interest in actually solving regional or global problems: each site is considered in isolation from all others, so that questions about regional or global outcomes are never asked, and therefore never addressed.

In the case of Milstein Hall, the issue of stormwater runoff is particularly interesting given the provision of a vegetated ("green") roof. A more serious, heavy, and "intensive" green roof might have contributed significantly to the mitigation of storm runoff, but would not have been compatible with the architectural design. The actual green roof is thought of more as a nuanced pattern of colors than as a useful environmental feature.

Heat Island Effect, Non-Roof

Credit 7.1. It's hard to take this credit seriously when vegetated campus sites get points for using relatively reflective pavement for drives and parking areas. Is anyone really concerned that Cornell is heating up when asphalt paving is used? In any case, I presume that this credit is obtained because concrete with a solar reflectance index of 29 or higher—actually, it has an SRI of about 47—has been used for hardscape areas around Milstein Hall. The SRI is defined on a scale of 0 (black) to 100 (white), so a dark asphaltic pavement would presumably not qualify, although it is not at all clear that its use would have any negative impact on anything. In fact, the final LEED review indicates that 58 percent of the 39,110 square feet (3,633 square meters) of site hardscape is paved with reflective concrete, satisfying the criteria for this credit.

Heat Island Effect, Roof

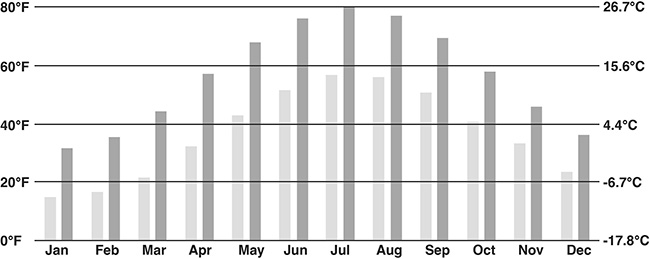

Credit 7.2. This is where a credit can be earned by having a vegetated roof. The green roof doesn't do much for stormwater control, and isn't at all necessary to reduce the heat island effect—any light colored roofing material would do as well or better. It's also not clear that having a light (cool) roof saves energy in this climate, where basically half the year is governed by heating rather than cooling loads (fig. 20.9). According to the U.S. Department of Energy: "Your climate is an important consideration when deciding whether to install a cool roof. Cool roofs achieve the greatest cooling savings in hot climates, but can increase energy costs in colder climates if the annual heating penalty exceeds the annual cooling savings."15

Figure 20.9. Ithaca's climate graph (average highs and lows for each month) shows that roughly half the year is governed by heating rather than cooling loads.

Milstein Hall's vegetated roof, while comprising most of what appears as the building's roof—other than about 1900 square feet (177 square meters) of skylights—covers only 60 percent of the actual building roof area, since much of the concrete hardscape surrounding the "building" is really a roof for below-grade spaces.

Light Pollution Reduction

Credit 8. Not even close. In a previous, and unbuilt, competition-winning scheme for Milstein Hall designed by Steven Holl, the idea of the building as a metaphorical lantern was actually exploited as a positive value. OMA's design is no different in that respect, as floor-to-ceiling wraparound glazing does nothing to mitigate light pollution. Architecture studio instruction promotes all-nighters as a de facto hazing ritual, so the glass facades of both schemes—projecting this idiocy as a point of pride for the community's "enlightenment"—is no accident.

Notes

1 This comment, and many that follow, appear in my summaries and critiques of the LEED Green Building Design & Construction Reference Guides. See Jonathan Ochshorn, "Links to my summary and critique," unpublished writing, here.

2 Values for building and site area are based on educated guesses since I don't have access to the official data.

3 "Since the billionaire's plans for the world's largest wind farm fell apart in the Texas Panhandle, Pickens has edited his much-hyped 'Pickens Plan' to focus primarily on his other big business interest: natural gas." Jennifer Alsever, "Pickens Plan no longer features wind energy," NBC Business News, Dec. 14, 2010, here.

4 "Environmental Issues," in "Sustainable Sites, Credit 3," USGBC, LEED 2.2 New Construction, 44.

5 Milstein Hall occupancy estimates provided by Matthew Kozlowski, Project Coordinator, Facilities Engineering, Cornell University in email to the author dated Nov. 30, 2011.

6 "If shower/changing facilities are located in another building, be sure that the building allows project occupants full access to the facilities during the same hours as the project building." "LEED Project Submittal Tips: New Construction 2009," Green Building Certification Institute, Dec. 23, 2011, 4, here.

7 "LEED for New Construction Application Review."

8 See, for example, Lloyd Alter, "Getting Person out of Car and Onto a Bike Saves More Energy & Carbon Than Going Net Zero," Treehugger Voices (updated Aug. 30. 2020), here.

9 "You can lead a horse to water… But you can't make it drink. In other words, bike racks and showers will probably not be enough to encourage biking in an area that's unfriendly to bicyclists. If you're thinking of pursuing this credit, first consider the realities of the neighborhood around your project. Is it realistic that building occupants will ride bicycles and make use of the bike racks and storage or the shower facilities? It's important to consider whether the intent of this credit will bear out in reality or if your resources might be better allocated elsewhere." "NC 2009 SSc4.2: Alternative Transportation—Bicycle Storage and Changing Rooms," LEEDuser.com (website no longer available).

10 See, for example: "Ridesharing & Carsharing," Cornell Sustainable Campus, here.

11 "Transportation—University Ave. Parking Lot Redbud Woods: A Controversial Development Case," Cornell Sustainable Campus (website no longer available).

12 Daniel Aloi, "Construction under way on Milstein Hall project," Chronicle Online (Aug. 4, 2009), here.

13 "Economic Issues," in "Sustainable Sites, Credit 5.2," USGBC, LEED 2.2 New Construction, 73.

14 "LEED for New Construction Application Review."

15 "Cool roofs," Energy Saver, https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/cool-roofs. See also: Tyler, "Rethinking Cool Roofing." In particular, Figure 1 shows a net loss in energy savings for all U.S. cities modeled except for Phoenix and Miami when a "cool roof " is used.

contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 19 |