Building Bad: How Architectural Utility is Constrained by Politics and Damaged by Expression

contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 13 |

14. THE COMMUNAL BEING AND THE PRIVATE INDIVIDUAL

Humans in developed capitalist societies, as a young Karl Marx argued in 1844, live two lives:

Where the political state has attained its full degree of development man leads a double life, a life in heaven and a life on earth, not only in his mind, in his consciousness, but in reality. He lives in the political community, where he regards himself as a communal being, and in civil society, where he is active as a private individual, regards other men as means, degrades himself to a means and becomes a plaything of alien powers.1

This split personality manifests itself in the realm of art and architecture, where one finds both types of expression—the idealism of the communal being as well as the self-interested behavior of the private individual—but not necessarily so neatly bracketed within the two realms of man's "double life." Rather than finding the expression of freedom, democracy, equality, and community exclusively in the public (communal) domain and the expression of wealth, power, and status exclusively in private or corporate architecture, all forms of expression may at times appear in all buildings. Each individual, corporate, or public entity manifests this split identity, so the types of expression consistent with both sides (i.e., both the private/self-interested and political/communal) may well show up in commercial buildings and private residences; while public or communal architecture also exists in a competitive environment—cities and states engage in economic competition against other cities and states; nations engage in global competition against other nation-states—so that symbolic evidence of wealth and power often becomes fused with the ideals of democracy, freedom, and community in public architecture.

While architecture's materials and geometries do not contain within themselves symbolic or expressive content, there is, nevertheless, some objective basis for identifying freedom, democracy, equality, community, wealth, and power as common expressive tropes. For example, when the Romans deployed "massive monolithic columns," not only were they "a symbol for the domination of Rome, [but] an equal degree of power was displayed in their transport and erection."2 In other words, the necessary expertise, wealth, and power that made these structures possible was understood at the time—immediately and objectively, by rich and poor alike—not by decoding messages hidden in the forms, or by accessing repressed or unconscious psychological motivations, but simply by observing and drawing logical conclusions from the size and weight of the stones, and the effort (requiring wealth and literal power) necessary to quarry them, transport them, and erect them.

FREEDOM

In the Metropolitan Museum of Art's "Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera" show, which opened in 2018 in New York City, the following curatorial text appeared on the wall: "Abstract Expressionism was promoted as exemplary of American democracy and freedom during the early years of the Cold War, and Pollock's art began exerting an international influence in this context. He reinvented the medium of painting as experiential, a kind of performance. Well over fifty years after their creation, these works retain their audacious dynamism and sense of daring."3 From these three sentences may be gleaned many of the principal means and purposes relating to the expression of democracy and freedom. Most importantly, there is Pollock's "audacious dynamism and sense of daring" which expresses the ideal of freedom precisely by breaking conventions. To repeat and reprise what has gone before is, of course, just as valid an exercise in freedom as to break boundaries and defy conventions; freedom is, after all, the ability to do whatever you want to do (albeit subject to your control over the property that you are doing something to, while not transgressing the boundaries of someone else's property). But doing nothing new or daring, while an example of freedom, is not typically a viable expression of freedom. In other words, the ideal of freedom is to break free of existing constraints, and not merely to use one's property to further one's own interests, against all others. It is that ideal that is expressed in paintings such as Pollock's.

According to the curatorial gloss, this expression of freedom was "promoted … during the early years of the Cold War." This shows that ideals of freedom can be deployed as propaganda, not only to reinforce and express competitive values within the home country, but also against rival economic systems. And the use of art (or architecture) as propaganda has no necessary or intrinsic relationship to the actual formal characteristics of the work itself. Deborah Howell-Ardila, citing another instance of Cold War competition, argues that "built forms convey no inherent political meaning; the same modernist style of the FRG's [West Germany's] first transparent (and thus 'democratic') Bundestag in Bonn, for example, had been used to fine effect by Benito Mussolini for the fascist party headquarters in Como, Italy."4 Not only that, "two heroes of the modern movement, Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe (both of whom played prominent roles in shaping the new 'democratic' architecture of the FRG) had entered Nazi-sponsored design competitions … thus acknowledging the flexibility of architecture's political significance."5

In extrapolating from painting to architecture, there is only one minor disclaimer. Architecture, unlike painting, is not only a means of expression, but is also a vehicle to support various utilitarian activities. This, by its very nature, constrains the unfettered expression of freedom, but also, paradoxically, makes that expression—where it occurs—all the more potent. As an example, consider the rebuilding of the World Trade Center towers in New York City. Daniel Libeskind's unbuilt proposal, "a sharp-angled skyscraper, topped with a twisting spire,"6 deploys two modes of expression, each of which gained quite a bit of public support. One type of symbolism is gratuitous and inane, that is, setting the tower's height at exactly 1,776 feet. This height references the date of America's Declaration of Independence, at least when measured in imperial units; the same height expressed as 541 meters would be perceived as unremarkable, unless one was commemorating, for example, the year when "Bubonic plague appears suddenly in the Egyptian port of Pelusium."7The other form of expression is more analogous to Pollock's "audacious dynamism and sense of daring": the unexpected distortion of the tower's form from what is considered economically, structurally, and functionally appropriate.

Yet although Libeskind won the competition for the new World Trade Center master plan, his expressive "Freedom Tower" design, intended by the competition's organizers only to illustrate the potential of the master plan, was never seriously considered. "There was no guarantee that the architecture from the master-plan competition would be built; it was intended to get people excited about a master plan. . . . In fact, by the time Libeskind had won, [developer Larry] Silverstein had already hired David Childs, an architect at Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill." Whereas Libeskind's proposal was an inefficient and expensive expression of freedom, Childs's design was precisely the opposite, prioritizing structural and functional efficiency. Even the name, "Freedom Tower," was replaced with something explicitly conservative and nostalgic: "1 World Trade Center." Michael Kimmelman, architecture critic for the New York Times, contrasted the expression of freedom that could have been—"to show New York's indomitable spirit: the defiant city transfigured from the ashes"—with the attitude actually taken, one that "implies (wrongly) a metropolis bereft of fresh ideas." For Kimmelman, having "fresh ideas" can be understood at the scale of architecture—through a building's unconventional ("fresh") design—but also at the scale of the master plan, for example, by incorporating "housing, culture and retail, capitalizing on urban trends and the growing desire for a truer neighborhood, at a human scale."8 However, only the former can be understood in terms of the expression of freedom; the latter is simply the critic speculating about the utility of deploying mixed occupancies on the site.

Instead of acknowledging the essence of defamiliarization as the expression of freedom, historians and critics often prefer to wallow in the subjectivity of psychological or pseudo-scientific speculation, whether invoking Freud's speculative theories of a death drive or Sigfried Giedion's "cosmic" vision linking art and Einsteinian relativity. The point is not to validate what architects or beholders think about their motivations or intentions in creating or interpreting defamiliarized buildings; on the one hand, one cannot peer into someone's brain to uncover a "true" motive; on the other hand, whether a motive is articulated at the moment of creation or extracted on the psychoanalyst's couch only reveals to what extent that motive has been informed by personal experience or appropriate cultural frameworks. Immersed within an architectural culture in which defamiliarized formal strategies have become prevalent, the desire—the necessity—of architects and beholders to compete within that culture will, in and of itself, motivate them to internalize the critical frameworks that have emerged within that culture. These critical frameworks are adopted—like the phenomena they purport to explain—not because they are true, but because, within their own competitive critical sphere, they have proven themselves effective in promoting a particular stylistic tendency.

The point, then, is to find an objective explanation of defamiliarized architectural production within modern capitalist democracies that does not rely on the self-serving subjectivity of critical artistic frameworks. And this brings us to the observation that all instances of the avant-garde can be explained as expressions of capitalist freedom. Those architects and their clients who choose to deviate from cultural norms by defamiliarizing their architectural production do so, first, in a competitive environment where being noticed (having notoriety) is deemed useful and, second, where freedom—the permission (compulsion) to do what one wants with one's property—is enshrined as a basic tenet of capitalism. Thus, the idealization of freedom as a heroic refusal to accept bourgeois conventions, rather than representing some threatening or revolutionary impulse, has an entirely reactionary content. This is not because the freedom being invoked is an illusion, but, to the contrary, precisely because it is real and oppressive. As explained by Karl Held and Audrey Hill, "freedom and equality are hardly an idyllic matter."9

DEMOCRACY

If the expression of freedom in art and architecture is clearly linked to the reality of freedom in capitalist democracies, examples of the expression of democracy in art and architecture are harder to find and more difficult to explain. Of course, one can cite the trivial case where buildings that house democratic institutions come to symbolize the idea of democracy: "For at least 2,500 years," according to Deyan Sudjic, "people have assembled to participate in and observe democracy in action. The environments in which democratic debate takes place can be seen as a physical expression of mankind's relationship with the ideals of democracy."10 Yet, even in those cases, it is not clear that "democracy" itself is being expressed. Instead, it may be that the formal qualities of legislative (parliament) buildings, for example, are more likely to express intimidation, authority, and legitimacy than the ideals of democracy. Sudjic admits as much when he argues that the "classical language of architecture has been used more than any other to create monumental parliamentary buildings that both inspire and can also intimidate in their representation of the democratic ideal"; or that "the architectural language … relied upon an established political tradition to reflect its authority. None more so than the fledgling United States of America which looked to Greece and Rome to legitimise its own republic."11

In the same way, the mere provision of a gathering place, whether indoors (the "town hall") or outdoors (the "public space"), is still often conflated with the ideal of democracy: "In 2011, Occupy Wall Street and Cairo's Tahrir Square protests sparked the publication of a spate of architectural texts on the use of public space, the rise of a democratic network culture, and the rethinking of public policy."12 Yet such spaces express democracy, not because there is anything particularly "democratic" about their form or structure (except for the trivial fact that they can physically accommodate large groups of people) but because they have become associated with specific protest movements that have, in turn, been linked with the ideal of democracy.

The idea of a democratic architecture has also been applied to buildings that are pleasing to, or used by, the masses, whether libraries, shopping malls, or railway stations. Joan Ockman, for example, asks if Rem Koolhaas's "radical gesture" of "overturn[ing] all the established hierarchies" at the Seattle Public Library was "a democratizing one, an effort to make an august public institution more crowd-pleasing and friendly?"13 Aaron Betsky argues that "our railroad stations are our contemporary architecture of democracy [because] they are open and accessible, they are shared spaces, they bring us together, and they celebrate all that gathering and connecting with grand and often beautiful structures."14 Koolhaas himself writes with unbridled condescension about the unending interior maze within airports and shopping malls that serves as "an architecture of the masses" and "one of the last tangible ways in which we experience freedom."15 Yet equating democracy or freedom with mere gathering, access, or movement is unconvincing, and Ockman's claim that "democratic architecture in late-capitalist society … has shifted over the last half century from a culture of monuments to one of spectacles"16 is both irrelevant and misleading. Examples of public gatherings, access, and movement—framed by architecture as spectacle—are hardly unique to modern democratic states (think of medieval cathedrals, markets, and fairs; or Roman games with their animal entertainments and executions; or festivals and celebrations in fascist Italy).

In fact, the word, "democracy" is most often simply added whenever freedom is discussed, since they are bound together in practice: Louis Sullivan, for example, makes this clear in an article directed at "The Young Man in Architecture" in 1900, defining democracy in terms of both freedom and restraint: "It is of the essence of Democracy that the individual man is free in his body and free in his soul. It is a corollary therefrom, that he must govern or restrain himself, both as to bodily acts and mental acts; that, in short, he must set up a responsible government within his own individual person."17

The linkage of democracy with freedom shows up, as we have already seen, in the Metropolitan Museum's claim that "Abstract Expressionism was promoted as exemplary of American democracy and freedom." On the one hand, freedom—to do what one wants with one's property, especially when defying cultural conventions—is clearly expressed in Abstract Expressionist paintings. But on the other hand, there are no obvious elements in such paintings that correspond to the idea of democracy—literally "rule by people" as translated from the Greek. Neither representative government, elections by majority vote, the checks and balances of legislative, executive, and judicial branches, nor any of the other conventional trappings of democracy appear, however metaphorically, in these paintings. The sociologist Herbert Gans makes the same argument in his response to Ockman's essay on democratic architecture: "Architects design buildings, but their buildings do not engage in politics, vote, or give money to campaigning politicians. They simply house a variety of human activities, including political ones, but these could be democratic, fascist, or communist, even if they were designed by an architect active in democratic politics."18 If freedom is the concept made visible by defying convention, democracy, invisible as a concept in its own right, comes along for the ride.

DEMOCRACY AND TRANSPARENCY

Ever since U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis argued in 1913 that "publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases, sunshine is said to be the best disinfectant, electric light the best policeman," the metaphor of transparency has become a popular ideological trope for democracy, although certain limitations and even negative consequences of transparency have also been noted. For example, "if the power of transparency is based on the 'power of shame,'" according to political scientist Jonathan Fox, "then its influence over the really shameless could be quite limited."19 Additionally, and precisely because transparency has become a factor in their operations, "democratic governments have incentives to obfuscate evidence."20 This "dark side" of transparency gets even darker, since "one person's transparency is another's surveillance [and] one person's accountability is another's persecution."21

As an expressive architectural element symbolizing democracy, the metaphor of transparency has not been particularly common. Where it does show up, most famously in the reconstruction of the Reichstag in Berlin by Foster + Partners in 1999, the architect's disingenuous claim that "within its heavy shell it is light and transparent, its activities on view"22 is contradicted by other observers. The architect and scholar Hisham Elkadi argues, for example, that "while glass seemingly provides a wider transparency and a social transformation, it actually denies any real interaction. … In fact, the glass dome of the Reichstag has replaced one form of presentation of power with another illusive and more subtle one. The transparency of glass is used in this case to conceal the contemporary powers of the Reichstag; the dome is a reference to tradition in order to conceal tradition."23

Peter Conradi framed a similar argument against the Bundestag in Bonn designed by GŁnther Behnisch in 1992:

The assertion that glass is transparent and therefore democratic is just as silly as the assertion that stone is not transparent and therefore authoritarian. It would be banal to assume that the transparence of Behnisch's new Bundestag … creates more democracy … Even in this see-through hall, the tax law of 1995 remains an incomprehensible, impenetrable piece of politics. The tactical evasions of a Wolfgang Schauble do not become more transparent in a glass assembly room.24

EQUALITY

Democracy is sometimes used as a stand-in for the ideal of equality—of a non-hierarchical society where everyone gets the same things. The architectural manifestation of this democratic ideal of equality consists of a non-hierarchical array of units in which repetitive functions, all with the same underlying geometry, can be housed. This is, however, not even remotely close to representing what equality means within democratic states. It confuses what bourgeois economists derisively call "equality of outcome"—the idea that governments ought to redistribute wealth to eliminate or reduce distinctions between rich and poor—with what they typically advocate under the rubric of "equality of opportunity." This latter version of equality necessarily creates losers and winners, being nothing other than the requirement to compete, and is consistent with freedom, liberty, and the equal application of law. Yet even the ideal of equality is not easy to express in works of architecture, since hierarchy—ordered difference—is inherent in much of what is built, irrespective of the architect's intention: up is different from down; high is different from low; edges are different from middles; south is different from north; and so on. The corner office, a paragon of unequal and hierarchical space, is inherent in rectangular office plans and, to that extent, precludes formal equality in such buildings. Perhaps the clearest expression of the ideal of equality shows up in apartment houses, hotels, jails, strip malls, and suburban housing developments—that is, in architectural and urban forms where repetition of a standard module is consistent with the utilitarian functions operating within the overall composition.

Yet this vision of a non-hierarchical democratic order based on the ideal of equality is at odds with the most famous articulation of a democratic architecture. For Frank Lloyd Wright, democracy did not mean equality of outcome, but rather signified an individual's freedom to choose, within an idealistic and idiosyncratic version of capitalism based on "ground free in the sense that Henry George predicated free ground" and "money not taxed by interest but money only as a free medium of exchange."25 As to how those "democratic" ideals would be expressed, Wright could only point to his own buildings, for example, his Usonian projects, as "expressing the inner spirit of our democracy, which by and large is not yet so very democratic after all."26 Yet it is clear that Wright was not interested in obliterating class distinctions or creating a one-size-fits-all template to express the ideal of democratic equality. "In the buildings for Broadacres," he argued in 1935, "no distinction exists between much and little, more and less. Quality is in all, for all, alike. The thought entering into the first or last estate is of the best. What differs is only individuality and extent. There is nothing poor or mean in Broadacres."27 What Wright means—by suggesting that "no distinctions exist between much and little, more and less"—is not that one should eliminate distinctions between "much and little, more and less," but rather that one should imbue all the architecture in Broadacre City, no matter its size, with the same quality of design. Quantitative differences—class differences—are not abolished or suppressed; equality of outcome is never the goal.

Christian Norberg-Schulz, like Wright, agrees that "democratic" architecture should not be concerned with the expression of equality. Unlike Wright, who had no problem with the expression of social inequality, Norberg-Schulz is concerned that class differences within capitalist society constitute a social embarrassment that should be suppressed, although differences in occupation—function—remain worthy of expression, except in the domestic sphere:

In a democratic society it may not be right to express differences in status, but it is surely still important to represent different roles and institutions. Our individual roles should probably not show themselves too much in the dwellings, as this would contradict the democratic equality of private persons. But our places of work should be differentiated to show that the individual roles participate in varying phenomenal contexts. The surgery of a physician should not only be practical, it must also appear clean and sanitary. In this way it calms down the patient. The office of a lawyer, on the contrary, should soothe the worried client by appearing friendly and confidence inspiring, at the same time as it expresses that the lawyer is an able man.28

What Norberg-Schulz advocates is an architecture of explicit manipulation, referencing techniques more commonly associated with advertising and persuasion: it is not enough for architecture to merely function. Architectural expression must also alter the mental and emotional state of building occupants so that they are better able to assume the roles assigned to them by the architect, presumably acting on behalf of the building's owner or tenant. While it is possible that the surgery actually is clean and sanitary in addition to appearing to be clean and sanitary, and while it is possible that the lawyer is actually competent in addition to appearing to be competent, it is easy to see how this attention to the techniques of appearance and persuasion, made independent from real performance and behavior (utilitarian function), can lead to all sorts of deceitful, if not dangerous, practices.

COMMUNITY

Stone, as exemplified in the prior discussion of Roman monoliths, often celebrates and expresses wealth and power. Yet stone can also be deployed as an idealization and expression of community. This occurred in postwar Berlin, in reaction to the alleged "inhumanity" or "superficiality" of modernist architecture and urbanism, to which stone's apparent solidity—and a renewed interest in traditional (although criticized as "nostalgic") community and pedestrian-friendly urban design—was offered as an antidote. Yet, like the facile equation of transparency and democracy, even such seemingly benign references to traditional stone-faced architecture can be fraught with controversy. Hans Kollhoff, for example, complained that—at least in the context of postwar Berlin—"every architect who takes a stone in the hand is accused of being a fascist."29

The expression of community is thus invariably double-sided, with the ideological battles fought in postwar Germany over the alleged political content of merely formal arrangements hardly an isolated exception. On the one hand, the expression of community, like that of democracy, can occur simply when utilitarian forms designed to accommodate groups of people (communities) become associated with that activity. This happens, for example, in sports stadiums, where a community of fans gathers to cheer on their local team, or even in the parking lots outside the stadiums, where community members gather for "tailgate" parties. Yet even, or especially, in such cases, the dark side of community is easy to spot: the community of fans is often explicitly antagonistic to fans of the opposing team, with taunting or physical altercations commonly encountered.30

Architects may adopt explicit formal geometries that have come to "mean" or express the ideal of community—things like front porches or stoops that occupy and define a semi-public space between the explicitly public right-of-way (street) and the private domain of the house or tenement building—based on the memory of cultural practices from prior times. But, as noted in Chapter 7, times have changed, and the historic sense of community embodied in urban patterns associated with specific building elements like porches and stoops is increasingly anachronistic. Where actual community does persist, it is always on an exclusionary basis—this is made unambiguously clear when politicians or community leaders talk of the "black" community, the "LGBTQ" community, the "alt-right" community, and so on. Even where the ideal of community is invoked on an apparently inclusive basis, for example, when the concept of a "people" is invoked, this national community—"the totality of a country's inhabitants whom a state power defines as its members … regardless of the natural and social differences and antagonisms between them"31—is, nevertheless, explicitly, and ruthlessly, exclusionary with respect to the other "peoples" of the world, with whom they are forced to compete.

Thus, the architectural expression of community is mostly self-evident and trivial in buildings like community centers, stadiums, or other community gathering places where the sign on the door and the purely utilitarian organization of form and space—rather than any explicit symbolic system of meaning—create a de facto expression of community, having become associated with the reality of community gathering that takes place therein. On the other hand, where explicit symbols of community are deployed, such as porches and stoops intended to invoke a memory of what once might have functioned as a communal street, they tend to become merely anachronistic expressions of community, betraying the absence of actual community.

WEALTH AND POWER

Not only wealth and power, but the lack of wealth and power, can be expressed in works of architecture. For example, material qualities that appear to be cheap or ubiquitous lend themselves to architectural expression in two ways: first, when a material's cheapness or ubiquity is consistent with the building's function; and second, when a material's cheapness or ubiquity is self-consciously deployed as a form of irony. An example of the former is traditional public (social) housing, where being cheap and common is implicitly part of the design brief. The idea is to attach a stigma to the building itself because "anything well-designed will be too appealing to eligible tenants, thus discouraging them from ever leaving. So affordable housing should not only be cheap, it should look cheap."32 An example of the latter is Frank Gehry's early use of corrugated metal, sheet metal, or chain-link fencing as part of building enclosure systems, or his later use of cheap plywood as a finished interior surface within expensive and culturally sophisticated buildings.

Materials that appear to be expensive and unusual (rare), or that require the deployment of great effort to transform them from their natural state, also lend themselves to architectural expression, primarily as manifestations of wealth and power (and, as argued by John Ruskin, as representations of devotion or sacrifice). But none of this is absolute; a material such as glass, to take but one example, can express wealth and power yet can also be used in modest and prosaic ways.

Because glass is cheap and ubiquitous in modern culture, it may not be self-evident how it can still be deployed as a sign of wealth and status. In fact, there are two primary means: first, by using large and non-standard (i.e., expensive) sizes, often with sophisticated metallic coatings or tints, laminations, fritting, or various types of heat strengthening; and second, by "capturing" particular types of views that only money can buy—whether urban (with the city viewed from a dizzying height, abstracted from the noise and smells of the quotidian work force below and transformed into a silent and sublime expression of human power) or natural (with large expanses of meadow, woods, ocean, lake, or stream providing the same sense of the sublime).

There are many manifestations of these expressive strategies, and numerous variations determined, in part, by whether the transparent surface is viewed from the inside looking out as opposed to looking in from the outside; and there are also variations in both of these points of view (i.e., inside looking out versus outside looking in) depending on relative levels of illumination on the inside versus the outside, levels that are typically inverted during the daytime and nighttime hours. Glass may well cease being transparent, and appear reflective or opaque, from the vantage point of an observer looking from an environment with higher levels of illumination than the environment on the far side of the glazed surface. Thus, a glazed building enclosure may appear impenetrably black when viewed from the outside on a sunny day; the same enclosure may appear entirely transparent when viewed from the same vantage point at night if the interior spaces are illuminated. Similarly, glazed surfaces may block views of low-lit exteriors when viewed from well-lit interior spaces, while permitting views of sunny outside spaces during the daytime.

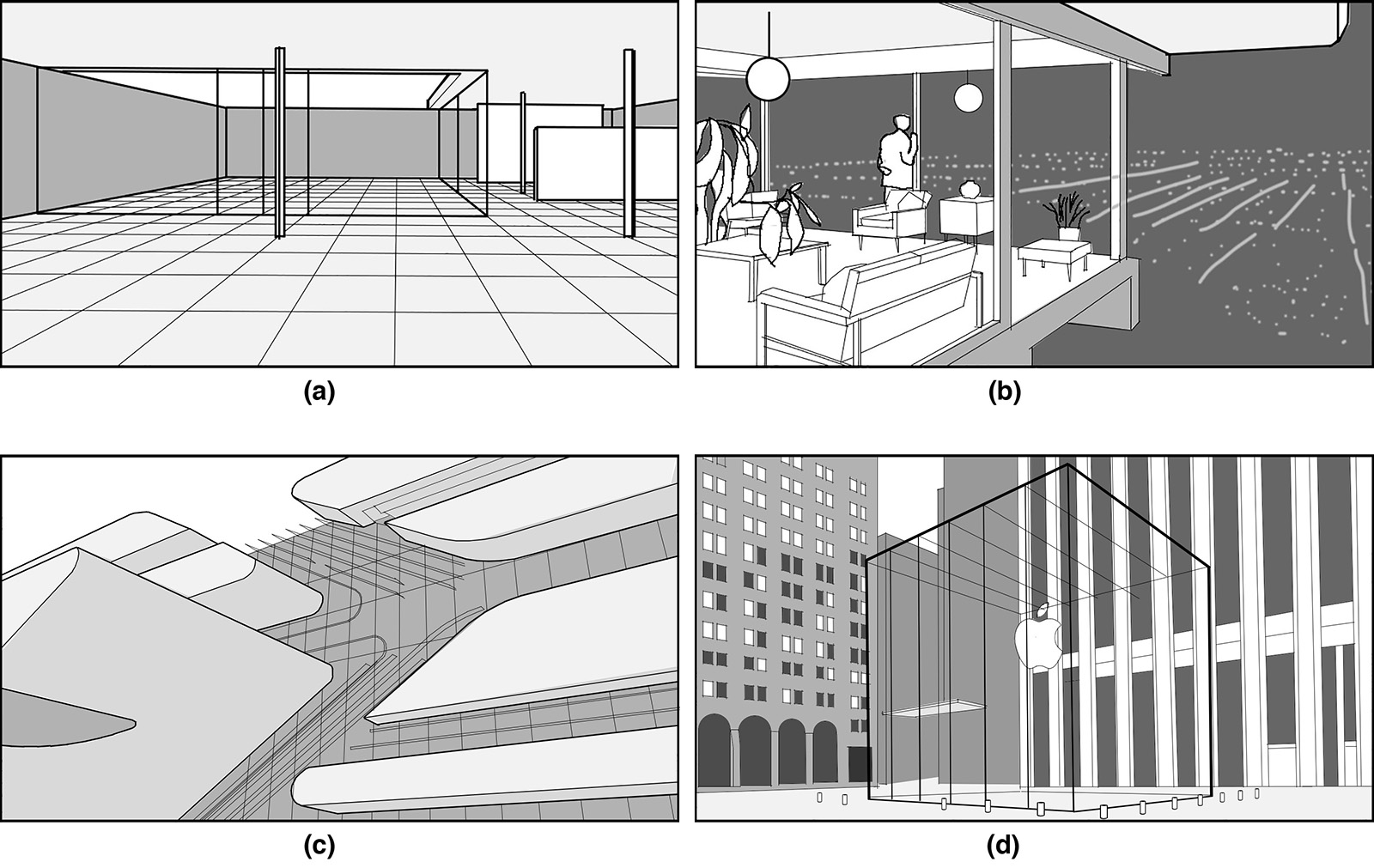

In Figure 14.1, four expressive strategies for the use of glass are illustrated. The first involves an expression of transparency that establishes visual continuities between exterior and interior spaces. Most commonly, walls and floors—and sometimes ceilings (soffits)—are extended from an inside space to an outside space, with the glazed boundary (enclosure) that separates inside from outside visually minimized. In this way, the idea that the outside is outside the inside and that the inside is inside the outside, is defamiliarized, or called into question, by the use of large and expensive surfaces of glass. Aside from the expression of expense, common to all strategies by virtue of the size and sophisticated composition of the glass itself, the expression of property is made explicit, at least to the extent that the walls used to express spatial continuity between inside and outside also create a bounded domain from which all others are physically excluded. Mies van der Rohe's various Court House projects from the 1930s and 1940s, in which interior spaces flow seamlessly into bounded gardens (Fig. 14.1a), are perhaps the best examples of this first case, although the essential ideas show up in many other built works.

Figure 14.1. Four manifestations of transparency: (a) expressing visual continuities between outside and inside in Mies van der Rohe's Row House with Interior Court project from about 1938; (b) linking the interior to a spatially separated, but particularly sublime exterior in Pierre Koenig's Case Study House #22—the Stahl House—in Los Angeles from 1959; (c) framing the solid (opaque) elements of the enclosure system as figural, or sculptural objects in Zaha Hadid's Pierresvives in Montpellier, France from 2012; and (d) defamiliarizing structure and enclosure in the form of an all-glass box in Bohlin Cywinski Jackson's Apple Store, Fifth Avenue in New York City from 2006.

The second case is similar to the first, in that the enclosure plane is meant to disappear. However, rather than using this transparency to create a sense of interior and exterior spatial continuity, transparency is here used to link the interior to a spatially separated, but particularly sublime, exterior, whether consisting of city, park, farmland, forest, lake, stream, or ocean. The first case may well be triggered by a desire for privacy and enclosure, since exterior space can be contained with walls that begin inside and extend outside, seemingly without interruption. The second case also achieves privacy, but not by enclosure. Instead, privacy is achieved by literally taking ownership of sufficiently vast amounts of property from which curious onlookers are excluded, or by gaining metaphorical ownership of the view itself—perhaps by an adjacency to vast distances that cannot be easily inhabited (lakes, oceans, and so on) or by building high enough above adjacent structures to preclude surveillance from below. Of course, it is possible to "own the view" using only conventional windows, but the most dramatic expression can be found with large expanses of glass as occurs, for example, in Pierre Koenig's Stahl house in the Hollywood Hills, looking over the city of Los Angeles (Fig. 14.1b).

The third case aims not so much to link exterior and interior space, but rather to frame the solid (opaque) elements of the enclosure system as figural, or sculptural, objects. As in the first two cases, the necessary continuity of enclosure is established by glazing elements that—even while joining together the solid elements—are meant to visually disappear. The difference is that in the first two cases, the enclosure "plane" is meant to disappear completely so that the exterior is brought into focus (or the interior, when viewed from the outside), whereas in the third case, the solid portion of the enclosure system itself is meant to be viewed as a figural object, and any exterior spaces, while visible from the interior (or interior spaces, even if visible from the exterior), are not directly relevant to the figure-ground or solid-void experience of the enclosure system. Zaha Hadid utilizes this framing device in the Pierresvives building in Montpellier, France (Fig. 14.1c), a combined archive, library, and sports department within an articulated enclosure.

The fourth case requires an enormous investment in material and in engineering to overcome the inherent brittleness of glass—a property that under ordinary circumstances precludes its use as building structure. Here, the building enclosure is not so much made invisible (since it is precisely the heroic gymnastics of the glass that is intended to be foregrounded) as it is made incredible. The already canonical example of this type of expression is the Apple Store on Fifth Avenue in New York City (Fig. 14.1d),), designed by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson in 2006, and then redesigned and rebuilt with even fewer structural glass elements in 2011.

It is possible to use two or more of these strategies in various combinations, or to invent other formal devices utilizing glass that transcend the default expectation of being a mere window in a wall. And it is certainly true that all of these and other applications of glass may well express countless other things—not only ideas about wealth, power, democracy, and freedom—to those who design them and to those who behold them. Large expanses of glass in all these cases are not only expensive to build, but also impose an energy penalty and contribute to global warming—negative consequences similar to those discussed in relation to thermal bridging in Chapter 12.

Notes

1 Marx, "On the Jewish Question," 220.

2 Sahotsky, "The Roman Construction Process," 46 (my italics).

3 Curatorial wall text describing the work of Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's "Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera" show in New York City that opened December 17, 2018. Transcribed by the author.

4 Howell-Ardila, "Berlin's Search for a 'Democratic' Architecture," 63.

5 Howell-Ardila, "Berlin's Search for a 'Democratic' Architecture," 75.

6 Elizabeth Greenspan, "Daniel Libeskind's World Trade Center Change of Heart," New Yorker, August 28. 2013, here.

7 Wikipedia, s.v. "541," last modified January 15, 2019, 10:37, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/541.

8 Michael Kimmelman, "A Soaring Emblem of New York, and Its Upside-Down Priorities," New York Times, November 29, 2014, here.

9 Held and Hill, The Democratic State (in Chapter 1, "Freedom and Equality—Private Property—Abstract Free Will").

10 Sudjic with Jones, Architecture and Democracy, 8 (my italics).

11 Sudjic with Jones, Architecture and Democracy, 20–21 (my italics).

12 Mimi Zeiger, "Koolhaas May Think We're Past the Time of Manifestos, But That's No Reason to Play Dumb," Dezeen, December 12, 2014, here.

13 Ockman, "What Is Democratic Architecture?" 71.

14 Aaron Betsky, "Railroad Stations Are Our Contemporary Architecture of Democracy," Dezeen, May 17, 2016, here.

15 Koolhaas, "Junkspace," 179.

16 Ockman, "What Is Democratic Architecture?" 67.

17 Sullivan, "The Young Man in Architecture," 118.

18 Gans, "How Can Architecture Be Democratic?" 119.

19 Fox, "The Uncertain Relationship between Transparency and Accountability," 665.

20 Hollyer, Rosendorff, and Vreeland, "Democracy and Transparency," 1191.

21 Fox, "The Uncertain Relationship between Transparency and Accountability," 663–64.

22 Foster + Partners, Projects, "1999—Berlin, Germany: Reichstag, New German Parliament," here.

23 Elkadi, Cultures of Glass Architecture, 48.

24 Conradi, "Transparente Architektur = Demokratie?" quoted in Howell-Ardila, "Berlin's Search for a 'Democratic' Architecture," 81.

25 Wright, An Organic Architecture, 28–29.

26 Wright, An Organic Architecture, 27.

27 Wright, "Broadacre City: A New Community Plan," 246.

28 Norberg-Schulz, Intentions in Architecture, 118–19.

29 "Neue Rechte am Bau?" (New Right-Wing in Architecture?), Der Spiegel 45 (1955): 244. Quoted in Howell-Ardila, "Berlin's Search for a 'Democratic' Architecture," 79.

30 Rookwood and Pearson, "The Hoolifan."

31 Gegenstandpunkt, "The People: A Terrible Abstraction," first paragraph.

32 Allison Arieff, "Affordable Housing that Doesn't Scream 'Affordable,'" CityLab, October 21, 2011, here.

contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 13 |