Building Bad: How Architectural Utility is Constrained by Politics and Damaged by Expression

contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 3 |

4. ACCESSIBILITY

The idea that accessibility is a function of buildings—that handicaps or disabilities should not impose needless barriers to access—has a relatively short history, although specific attitudes toward the disabled, ranging from the patronizing to the scornful, can be found over a much larger timeframe.1 In the U.S., early attitudes were characterized by a kind of moralistic benevolence in which "persons with disabilities were often viewed as part of the 'deserving poor,'" but by the 19th century, attitudes had changed in response to "industrial and market revolutions and the growth of a liberal individualistic culture" in which "persons with disabilities, increasingly deemed unable to compete in America's industrial economy, were spurned by society."2

While various particular conditions of the disabled provided fertile grounds for both moralizing attitudes as well as misguided fear-mongering, the creation of huge numbers of disabled citizens in the 20th century as a result of both war and industrial injuries changed the underlying logic of remediation. Early organizations of disabled persons (e.g., the Disabled Veterans of America, founded in 1920) and early examples of governmental intervention (e.g., the Veterans' Rehabilitation Act of 1918) specifically addressed the consequences of war injuries. Yet at the same time, the state's interest in appearing to take care of its wounded soldiers—derived at least in part from the need to attract future enlistees—is invariably matched by a reluctance to actually expend resources on citizens no longer useful in its war efforts.3

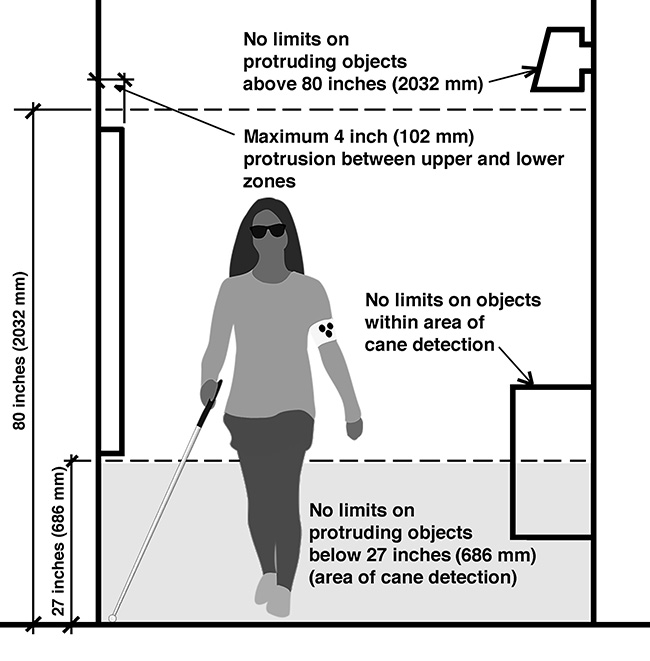

The specific history of accessibility legislation in the U.S. begins with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, not because it extended access to disabled persons (it did not), but because it established the "principle [that] discrimination according to characteristics irrelevant to job performance and the denial of access to public accommodations and public services was, simply, against the law."4 Prior to the passage of this legislation, in 1961, the American National Standards Institute issued its Specifications for Making Buildings and Facilities Accessible to, and Usable by, the Physically Handicapped (ANSI A117.1) as a voluntary consensus standard. This voluntary standard contained specifications for virtually all of the elements now explicitly required in both federal legislation and building codes: ramps or elevators to provide access to floors above or below grade; minimum dimensions for hallways and doors; minimum maneuvering space for wheelchairs within all rooms (typically implemented by requiring an unencumbered space in each room defined by a circle with a 5-foot, or 1.5-meter, diameter); curb ramps at street intersections; accessible ("handicapped") parking spaces; and the avoidance of physical elements that project ("protrude") more than four inches (102 mm) into circulation paths, unless they can be readily detected by those with vision impairments, that is, they are within so-called cane-sweep.5

Seven years after ANSI A117.1, the first piece of legislation was passed in the U.S. that actually mandated accessibility in buildings. However, the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 applied only to buildings financed with federal money, leaving business interests unfettered by such requirements. Up until this point, voluntary compliance with the ANSI Specifications was virtually non-existent.

The next important piece of disability legislation, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (specifically Section 504 of that Act), framed disability as a civil right rather than as a welfare issue, requiring that: "No otherwise qualified handicapped individual in the United States … shall, solely by reason of his handicap, be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance."6 As might be expected, the controversy surrounding passage of this legislation, beginning in the Nixon administration, centered around cost. Nixon, in vetoing the initial legislation in 1972, "claimed that the bill was 'fiscally irresponsible' and represented a 'Congressional spending spree.' He urged: 'We should not dilute the resources of [the Vocational Rehabilitation] program by turning it toward welfare or medical goals.'"7 Regulations to implement the legislation that ultimately passed in 1973 were postponed during the Carter administration, also due to concerns about cost. The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 introduced an exemption provision based on the concept of "undue hardship" that reappears in later legislation.

Both the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 applied only to federally financed buildings. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 extended such requirements to much of the private sector. While it is, and was, publicly lauded in idealistic and moralistic terms, the actual "back-room" political debates leading to its passage reveal a close attention to cost–benefit analysis, and the particular details of the legislation ensure that private interests are not damaged. In fact, politicians' speeches in favor of the ADA often demonstrate a combination of moral fervor along with a sensitivity to costs and benefits. Congressman Steny H. Hoyer's comments are typical:

We are sent here by our constituents to change the world for the better. And today we have the opportunity to do that. … Many have asked: 'Why are we doing this for the disabled?' My answer is twofold. As Americans, our inherent belief is that there is a place for everyone in our society, and that place is as a full participant, not a bystander. The second answer is less lofty. It is steeped in the reality of the world as we know it today. If, as we all suspect, the next great world competition will be in the marketplace rather than the battlefield, we need the help of every American. … We cannot afford to ignore millions of Americans who want to contribute.8

Congressman Steve Bartlett is even more direct: "ADA will empower people to control their own lives. It will result in a cost savings to the Federal Government. As we empower people to be independent, to control their own lives, to gain their own employment, their own income, their own housing, their own transportation, taxpayers will save substantial sums from the alternatives."9

To spare business the costs of actual remediation of existing structures under the ADA, the "undue burden" clause of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 reappears: "Title III provides that 'no individual shall be discriminated against on the basis of disability' unless providing such aids would 'fundamentally alter' the nature of the goods and services or result in an 'undue burden.'"10 This "undue burden" clause, together with a compromise agreed to by the bill's primary sponsor, make the ADA's accessibility provisions much less effective than the self-congratulatory speeches by its political supporters might lead one to believe. The so-called "fragile compromise" supported by Senator Tom Harkin altered the enforcement scheme in Title III of the ADA so that only injunctive relief was permitted, thereby providing "little incentive for plaintiffs and their lawyers to seek legal remedies." In other words, because no monetary compensation was included as part of a remedy, low-income individuals with handicaps would not have the means, and lawyers would not have the incentive, to seek such relief. Moreover, in the years since its passage, "the courts and Congress have actually taken steps that have worsened the problem."11 Such legislative and judicial maneuvering is hardly accidental, but rather reflects an explicit interest in limiting governmental intervention according to its impact on economic growth. As Senator Dale Bumpers explained in 1989: "We are obligated here to weigh the interest of the rights of the handicapped, which ought to be total, against what is obviously going to be quite a burden for a lot of small business people."12

As in the historical evolution of fire safety measures, moral sentiments are often expressed when social or environmental "problems" (i.e., damage to human or natural elements) are noticed. Such sentiments, which tend to frame as ideals the actions required for remediation, always differ from the actual responses to these problems in the following way: actual responses seek, not to solve problems per se, but to manage them in such a way that business interests are not threatened. It is not arguments about morality or safety—whether evaluating the case for accessible buildings or assessing the risk of fire—but rather calculations based on cost and benefit that tend to prevail. As Susan Mezey writes: "Reflecting its concern for the cost to business owners, Congress limited the ADA's mandate on accessibility of existing structures. … Owners of existing structures are only obligated to remove structural and communication barriers when 'such removal is readily achievable,' meaning 'easily accomplishable and able to be carried out without much difficulty or expense.'"13

Specifically, governmental intervention occurs only when, and to the extent, necessary; that is, only when private interests cannot themselves create the preconditions for continued, or optimal, economic growth. In the case of accessible building, private interests, on their own and in competition with each other, are generally unwilling to make their facilities accessible. Action is taken only based on government mandates that apply equally to all competitors. The availability of ANSI Specifications as a voluntary standard had virtually no effect on building access until it was effectively incorporated into law, first through individual legislative action in various states (e.g., Michigan, California, and North Carolina in the early 1980s) and then through federal passage of the ADA (1990).

Thus, accessibility has become a building function not because building owners or architects independently determined that such access was useful, but because governmental entities mandated conformance with accessibility requirements that had originally been developed as voluntary standards. The heart of these standards comprises two chapters, one dealing with so-called building blocks and the other defining accessible routes. Building blocks include guidance on such things as the configuration of floor surfaces, with or without changes in level; clearances for toes and knees; constraints on protruding objects; and standards for reach ranges (i.e., locations on a vertical surface that can be reached by someone in a wheelchair). Accessible routes consist of things like walking surfaces, doors and doorways, ramps, curb ramps, elevators, and platform lifts. Many of these elements have entered into the design vocabulary of contemporary architects, so that new buildings generally do not have issues with the provision of elevators or ramps or required turning spaces in accessible bathrooms.

However, one element in the standards—created to accommodate people with vision disabilities—remains widely misunderstood and ignored: constraints placed on protruding objects, that is, objects that extend ("protrude") into circulation paths in such a way that they cannot be detected by people with vision disabilities and thus present a hazard (Fig. 4.1). This issue has become increasingly important as works of architecture manifest non-orthogonal geometries in which elements, designed to challenge the orthodoxy of traditional vertical or horizontal surfaces, extend into circulation paths above the cane-sweep zone used by vision-impaired individuals to maneuver safely through the built environment. And non-conformance with this particular standard, as with all other access standards, is a problem not just for people with permanent disabilities, but for all people. Most individuals will experience at least temporary disabilities for which elevators or ramps, for example, will prove useful—even wheeling a piece of luggage, or a bicycle or baby carriage, in and out of buildings is facilitated by such mandates—and many humans experience temporary moments of distraction where rules constraining protruding objects may well prevent nasty collisions with building elements or surfaces.

Figure 4.1. Limits of protruding objects.

Milstein Hall—the architecture facility at Cornell University designed by Rem Koolhaas and OMA—will serve as a case study illustrating how architectural design concepts may come into conflict with accessibility rules, in particular, those that determine how far protruding objects can extend into circulation paths in buildings. The architects' own description of their intentions is revealing. Rather than being defined by mere walls or floors, the building is conceptualized as consisting of "plates" "punctured" by "the bulging ceiling," a "bump" that "continues to slope downwards on both sides," and so on.14 These bumps and collisions of sloping planes with floor and ceiling surfaces result in a sculptural composition that provides enticing views for photographers, but produces a dangerous landscape for humans moving through the spaces.

None of the protruding objects in Milstein Hall have a utilitarian (functional) basis. In the case of the sloping curtain wall that bounds an auditorium and a lobby (Fig. 4.2, left), the angled surface is entirely expressive, intended perhaps to represent the type of design freedom that was first articulated by early modernist architects (the idea of freedom as an expressive function is discussed in Chapter 14). Le Corbusier, for example, famously extolled the potential "freedom" of the ground plan: "The interior walls may be placed wherever required …There are no longer any supporting walls but only membranes of any thickness required. The result of this is absolute freedom in designing the ground-plan …"15 Where freedom for Le Corbusier is tethered, however tenuously, to some ideal of utility—note how the word "required" appears twice in this short quote, suggesting that the ability to adjust and position the "membranes" separating inside from outside has some rational ("required") basis—the freedom represented by the sloped wall in OMA's Milstein Hall composition is purely expressive and is not linked to any type of programmatic or utilitarian rationale.

Figure 4.2. Protruding objects in Milstein Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

This becomes even more clear when we examine another protruding object in the building, a sloping reinforced concrete column in the below-ground Critique Room (Fig. 4.2, right). The hazard of this sloping object for those with vision disabilities is self-evident, but perhaps there is a structural rationale: the doubly curved surface of the "dome," whose shape was modeled by the architects without recourse to any structural form-finding methodology, may have required some extra support at this point. In this case, perhaps the sloping column was suggested by the structural engineers to counteract the downward thrust of the heavy ceiling. As it turns out, the design of the sloping column, just like the shape of the reinforced concrete "dome," was not determined by structural necessity or structural efficiency, but rather by the architects, acting on their own. Apparently, they thought that a sloping column was somehow interesting, or appropriate, in that context, and incorporated it into their schematic design drawings before a structural model even existed. The structural engineers, eventually establishing a "dome" thickness of 12 inches (305 mm) and a dense pattern of steel reinforcement, had no need for the sloping column, but went along with the architect's aesthetic sensibilities and incorporated it into their structural model.16 Eventually, cane-detecting bars were added at the sloping curtain wall and below the sloping column (Fig. 4.3), providing some warning to people with vision disabilities.

Figure 4.3. Cane detection devices installed at Milstein Hall after the building was occupied, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

In fact, there are 20 instances where cane-detection devices were installed around sloping objects in Milstein Hall (Fig. 4.4), and several other instances where such devices should have been installed but were not. While these devices have some utility in providing warning of protruding objects to people with vision disabilities (or to distracted faculty, staff, or students), their utility is the result of an entirely dysfunctional set of design strategies which create such dangerous conditions in the first place.

Figure 4.4. All twenty cane detection devices installed at Milstein Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

Notes

1 A short, unpublished version of this chapter, excluding the discussion of protruding objects, was presented by the author as "What Sustainability Sustains," Hawaii International Conference on Arts & Humanities, January 2008.

2 Young, Equality of Opportunity, 5.

3 Dana Priest and Anna Hull, "Soldiers Face Neglect, Frustration at Army's Top Medical Facility," Washington Post, February 18, 2007.

4 Young, Equality of Opportunity, 10.

5 Protruding Objects, U.S. Access Board.

6 Young, Equality of Opportunity, 12 (ellipses in the original).

7 Young, Equality of Opportunity, 11.

8 Young, Equality of Opportunity, 2 (ellipses in the original).

9 Young, Equality of Opportunity, 3.

10 Mezey, Disabling Interpretations, 109–10.

11 Colker, The Disability Pendulum, 170.

12 Mezey, Disabling Interpretations, 110.

13 Mezey, Disabling Interpretations, 111–12.

14 "Milstein Hall Cornell University," OMA Office Work, here.

15 Le Corbusier and Jeanneret, "Five Points Towards a New Architecture," 100.

16 Ben Rosenberg, P.E. LEED AP (Senior Engineer, Robert Silman Assoc., Structural Engineers, New York), in videotaped interview with the author, June 9, 2011, https://youtu.be/xQP-e3OWSGE.

contact | contents | bibliography | illustration credits | ⇦ chapter 3 |